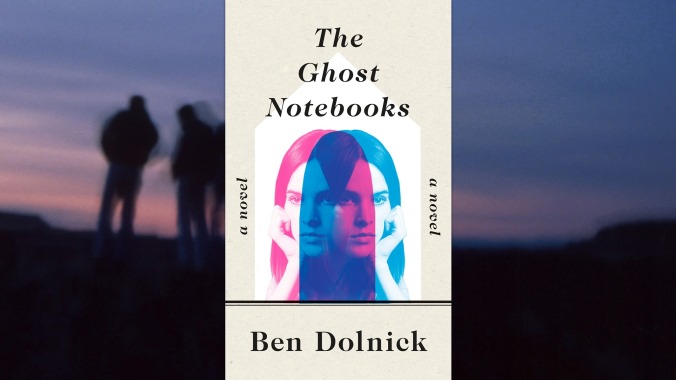

Ben Dolnick delivers compulsive readability, if not scares, in The Ghost Notebooks

It seems like a lark at first, as these things always do, when Nick Beron quits his job to follow his fiancée (whom he impulsively proposed to), Hannah Rampe, for her new role overseeing a remote museum. It’s a house dedicated to a philosopher who was obsessed with contacting his dead son, and which was the site of a murder some years before. Soon, there are bumps in the night, a diary reveals events that are years in the future, and Hannah—who once suffered a possession-like mental breakdown—grows distant as she immerses herself in the home’s macabre history. “The line between romantic getaway and lonely creepy farmhouse is, it turns out, fairly thin,” muses Nick, who will soon be pacing the house “like a lunatic in a Poe story.”

This is the premise for The Ghost Notebooks, the latest novel by Ben Dolnick, which uses the trappings of horror to explore and compound his pet themes of lost and confused young people. (Those who read it to be scared will be disappointed.) If life offers an unending number of ways to not be settled—especially for young creative types who are haunted by every missed opportunity and path not taken—then the infinite time and space of an afterlife can only magnify one’s unmooring. And in-between those forms of consciousness is death: immutable, omnipotent. It can’t be argued or reasoned with. Death isn’t interested in your shit.

Over a series of short, quietly powerful novels, Dolnick has emerged as an author of compulsive readability and real insights. He’s the kind of writer who can easily be overlooked, if not dismissed as a stereotype, as his characters are straight white guys, mostly adolescents or young men in some borough of New York, and the stories generally revolve around first loves, first heartbreaks, or the first time someone they know dies. These familiar elements feel fresh and immediate in his hands, though, demonstrating how it’s the storytelling and not the story that makes a book worthwhile.

He has a gift for metaphor, a way of expressing complex emotions and relationships with a pithy comparison that’s easy to understand but genuinely illuminating, and at the same time isn’t a cliché and never feels cutesy. Here, he describes the shell shock Hannah’s parents have from parenting someone who once suffered a nervous breakdown. “To have watched your child collapse is to live the rest of your life on a partially frozen pond,” he writes. This image is enough to carry their motivations through the entire book, especially their desperation as the ice begins to thaw.

Notebooks is Dolnick’s most thematically ambitious work, and while it maintains the clarity and broad sympathy that marks all his writing, it falters a bit as his narrative swings for the cosmos. It’s as though his premise and the ultimate point he wants to make are incompatible. Compare this to 2011’s You Know Who You Are, his best work, which marries smaller ideas to a broader scope and feels more cohesive and powerful.

The first act of the book shows Nick and Hannah’s relationship on a precipice. She’s laid off, they have different priorities, and he’s dubious about marriage—whether to her or in general, he can’t say. This section is rendered compellingly and believably, through Dolnick’s ability to suss out whole lives from tiny details and insights. And when they move to the museum and the darkness begins to fall, there’s an undercurrent of tension that’s all the more effective for never being directly commented on. Creepy noises and ghosts are bad enough, but should loyalty fall by the wayside if a malevolent force consumes someone you were already shaky about? It’s one thing for the Poltergeist mom to brave another dimension to rescue her daughter; when the going gets tough here, Nick might reasonably conclude there are other fish in the sea.

This dynamic gets flipped toward the end, however, and Dolnick’s thinness in making that transition is the book’s biggest weakness. Without revealing too much, it’s implied that love can essentially transcend death, a nice idea that’s unconvincing under the circumstances. It’s understandable why Nick feels the loyalty and devotion he does to Hannah toward the end, but Dolnick aims for a tearjerker finale he doesn’t earn because he’s already so well established that the two aren’t soul mates—or at least, they don’t have the kind of bond that would push through spectral planes. This is the kind of issue you only really notice after you’ve finished the book, as you reach the “Oh, that’s it?” final page, but it does make the book’s foundation feel retroactively weaker.

The Ghost Notebooks feels like it will be a transitional book in the context of Dolnick’s hopefully long career. If he builds on this and plays with genre conceits and grander themes in a more successful way his next time at bat, readers should expect great things.

Purchasing The Ghost Notebooks via Amazon helps support The A.V. Club.