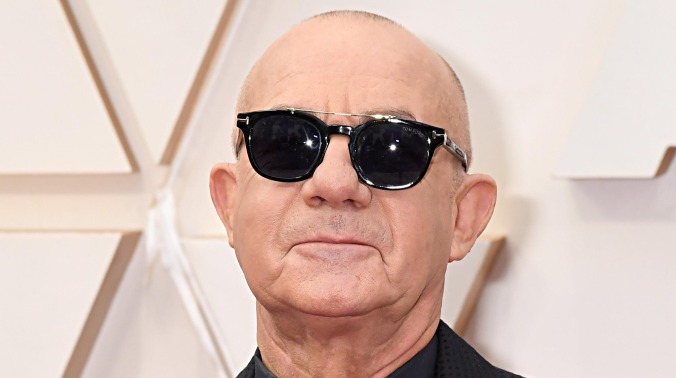

Bernie Taupin tells us what's pop, what's country, and what it's like writing with Elton John

Talking about his new book Scattershot, lyricist Bernie Taupin reflects on the early days of his career

Over 50 years ago, Bernie Taupin answered an ad for a lyricist in the newspaper. What happened next is practically myth: he connected with Elton John, and the two of them embarked on one of the most successful and long-running creative partnerships in music history. Now, he has some stories to tell.

Taupin’s new book, Scattershot: Life, Music, Elton & Me, released this week, is an appropriately named collection of stories from his humble beginnings in the English countryside to global success. Rather than focusing on a chronology, Scattershot jumps between geographic locations, from France to Los Angeles to Australia to Barbados. “I would sort of start writing about a specific point in time,” Taupin tells The A.V. Club, “and then suddenly by writing that, I would start remembering other things.”

At over 400 pages, there are a lot of other things. You already knew Taupin was a skilled writer from his lyrics, but he is equally adept at prose, charting out a fairly literary hero’s journey to the top of the world. Here, he tells us about how he wrote some of his and John’s biggest hits, what he thinks of the current crop of pop stars, and why Frank Sinatra left him more starstruck than anyone.

The A.V. Club: How did you go about putting this together? It’s such a long history. Had you been keeping diaries?

Bernie Taupin: No. Believe it or not, it started with a magazine article. There’s a fashion magazine called Bazaar magazine, and they had asked to write a piece. They did a photo layout with Brandi Carlile wearing Elton John outfits and impersonating Elton, and they asked me to write an accompanying piece with it about, basically, my first impressions of Elton when I first met him. I did that, and I really enjoyed doing it, and they loved the piece. They sent me this glowing letter saying it was one of the best pieces they had ever had submitted to the magazine and anytime I wanted to write anything else, feel free to contribute. So, I started writing others, just prose for the fun of it. And by the time I had written maybe three or four pieces, I suddenly realized, “I think what I’m doing is writing a book here.”

So I started writing from there for probably about two years. I’d write every day for a few hours, but with no specific ideas—I just wrote about what I wanted to write about. I didn’t go sort of A-to-Z through my life. The one thing I didn’t want to do was write a linear book. I think that’s what everybody does, you know, This is when I was born, this is where I’m at now. I just wanted to go all over the place, and be a geographical sort of travelogue.

AVC: In the early Los Angeles section—country music is something that’s near to your heart and you bring up a lot—you go off on this brief aside, ‘Oh, I wanted to write for Merle Haggard. But it didn’t really go anywhere.’

BT: That’s very much the idea of the book, hence the title, Scattershot. I think in the author’s note, if I start wandering off on another tangent when I’m talking about something completely different, that’s the way my mind works. So I wanted to write the book the way that my mind works. If I’m talking about going and visiting a particular club in Los Angeles, like say The Palamino, which was a famous country club in the Valley, if I mention somebody’s name I might go off on a tangent about that particular artist or having an interaction with them.

AVC: I didn’t know that you were such a big country music guy before I started reading the book. It was interesting to me, because it’s not the impression I had of the music that I know you for. What about that genre of music spoke to you?

BT: Well it certainly infiltrated our music. You say you wouldn’t have thought about that having listened to our music, but that’s the beauty I think of our music, is we’ve encompassed all kinds of genres over the years. It’s not always been straight pop. If you listen to the albums, there are quite a few country influences. And then we did the Tumbleweed Connection album, which is hugely influenced by what became Americana. They didn’t have that title back then, but Tumbleweed Connection was incredibly influenced by The Band, by Music From Big Pink and The Brown Album. Those two albums sort of kickstarted the whole Americana phase.

But from day one, the thing I gravitated toward country music for was the fact that they told stories, where contemporary pop when I was growing up really didn’t do that. You know, it was just straightforward, either rock n’ roll, or it was ballads, and they were usually romantic ballads. They didn’t really have a storyline that I connected with. I always wanted to write stories. The people that I first heard, the country records that I very first heard, were people like Johnny Horton, “The Battle Of New Orleans” and “Sink The Bismarck.” And then obviously Marty Robbins was a huge influence on me. The song that I always cite as the song that made me realize you could tell stories and also write songs for them was “El Paso.” One of the first albums I ever owned was Marty Robbins’ Gun Fighter Ballads And Trail Songs. And they were all stories. They were all cowboy songs. They just took me to another place, where contemporary pop music—I enjoyed it—but it didn’t do for me what narrative country music did. Narrative country music was really the blue touch paper for everything I did.

AVC: You mention in the book, and it’s also dramatized in Rocketman and is just a famous story about “Your Song,” that you had the lyrics and put them aside, and came back a few minutes later and Elton had—

BT: Well, it didn’t quite happen like that. I didn’t put them aside, he actually took them. Although Rocketman—50 percent of it is a fantasy, and it’s supposed to be, all the songs are chronologically in the wrong order—the actual scene in Rocketman when we write “Your Song” is actually pretty much how it happened, outside of the fact that his mom and his grandmother weren’t in the room when we were writing it. But I actually did write it at the breakfast table while everybody was sitting around—if you remember, and this is actually true, in the movie Elton picks up the piece of paper and goes, “This has got egg on it.” The original manuscript had egg on it and had coffee stains. He took it from me, went in the next room, and wham, bam, there you have it.

AVC: As you grew into the partnership, would your process stay kind of siloed like that?

BT: Yeah. What you see in the movie was the period in time when we were both living with his mother in the suburbs of London. For us, it was kind of like a little mini Brill Building. I’d be probably in the bedroom down the hall scribbling—I wouldn’t call them lyrics back then. I don’t know what they were. They weren’t poetry, certainly. I would just write sort of copious notes and he would take them into the living room, to the upright piano, and turn them into songs, which was magical because before that particular point I didn’t really have a great grasp on what writing songs entailed. I didn’t know things about bridges. I wrote sort-of verses, but I didn’t indicate what could be a chorus or what have you. But that came with time.

AVC: Would it ever be like the two of you sitting at the piano together?

BT: No. Never. That’s the sort of stereotypical image of songwriters, sitting together, smoking with their ties down and their sleeves rolled up and going, “Well, I think this word could go there, and what about this.” No, we never did that. That’s like out of the old movies, you know, George and Ira Gershwin hammering it out together.

AVC: Well, at the time, Lennon and McCartney had just had this huge decade of success. In your book, you talk about how they put your photo on the LP, which helped you become a more recognizable figure. Was that something the label wanted?

BT: No, they didn’t want it, we just did it. Back in those days, it was interesting creatively. We created our own album covers. We had this guy who did all of those album covers—a guy called David Larkham, who I talk about in the book, who was also a good friend. We would just present them to the record company. The record company didn’t do our album covers, we did them. We decided who went on them and who didn’t.

AVC: That was pretty striking, also, hearing about how record labels worked back then. It didn’t seem like you got much artist development, they kind of just let you go.

BT: We were lucky. At that period in time, the record companies were far more creative than I think they became later on, when they became conglomerates. Now, there’s only sort of three major record labels, where back then there was so many different ones. Even if there was a major label, it would have subsidiaries. We were very lucky to have existed in the time period we did coming up. We were really given free rein on what we did, both in the studio and with the creative ideas.

AVC: Backtracking a little, it feels like right now, at least on the American charts, country music is bigger than it’s been in a long time.

BT: Well that’s because country is become like pop. I mean, it’s not like real country anymore. There are very few artists that—there are so many that sort of straddle that line between pop and country and there’s no defining line anymore. It’s certainly not banjos and fiddles and steel guitars anymore. It’s pop basically. If you listen to an artist like—and they’re good, too!—somebody like a Maren Morris, she’s a pop artist. But for some reason, regarded as country.

AVC: At this point, if you have an acoustic guitar—

BT: Yeah, it’s very odd. It’s like when Taylor Swift started, she was supposed to be country. And I think she just realized, “Well, I’m not really country, I’m officially going to be a pop artist.” But there’s so many of them: Kacey Musgraves. Great artist, but not really country.

AVC: What is really country to you? Is it the instruments? The mythos?

BT: I think it a lot has to do with the subject matter and the sound of the record and what’s on them. I mean, country is steel guitar and fiddles, and there are country artists who sound more country than pop. One of the best artists out there right now I think is Zach Bryan. I think he’s great. Really, really talented. But again, he’s sort of leaning toward more of the Americana kind of thing.

I don’t like genres. It’s weird, being pigeonholed into something. Are you country, are you pop? I mean, basically everything is pop, because pop means popular. Bruce Springsteen’s pop. Neil Young’s pop. Frank Sinatra was pop. Anybody who’s popular is basically pop. I think people like to pigeonhole acts. It’s an aloofness. You know, they want to be thought of as “No, we’re rock n’ roll.” Yeah, you’re rock n’ roll, but you’re still popular, so … you’re kind of a pop artist. Back in the early days, back in the ’60s, if you look at old interviews with people like Mick Jagger when they started, they’d refer to themselves as a pop band. They wouldn’t do that now.

AVC: I think country is one of the last places that you have the framework. You have the Nashville songwriting system, you can get in that, get famous enough to just become a pop star, like Taylor Swift did.

BT: You’re right. It’s very interesting. It’s an interesting sort of dynamic. Everybody wants to put labels on people. I think maybe everything should be just called pop. But pop has become a dirty word, because people think it means it’s not very serious and it’s cheap. People don’t want to be pop artists, they want to be taken seriously. You can be taken seriously and be popular at the same time.

AVC: It seems like a lot of the pop artists who are taken the most seriously are the ones who go full-steam into being pop artists. Lady Gaga comes to mind—

BT: Right, exactly. Whoever’s top 40—I can’t remember people’s names, but these Cardi Bs and somebody the horse—

AVC: Megan Thee Stallion?

BT: Megan Thee Stallion! [Laughs] But that’s what I’m saying. I guess those are what people refer to as pop stars now.

AVC: You mention Frank Sinatra, which was also a cool aside in the book. You say that was one of the only people who made you really starstruck.

BT: Yeah, it was Frank Sinatra, man. Somebody asked me the other day, and they were disappointed I think because they wanted it to be more salacious, who had the most effect on you of anybody you ever met? And I said Graham Greene, without a doubt. The greatest novelist of the 20th century, that was my rock hero. But Frank Sinatra’s pretty close. When you’re in the presence of somebody like that and you think of their history and their backstory, it’s unbelievable. Plus, he was phenomenal too. One of the greatest voices of the 20th century.

AVC: Frank Sinatra is obviously beloved. If he gets any criticism as an artist it’s that he’s not a writer, and you are primarily a writer—

BT: Well, the thing about Frank Sinatra is that he was such a great interpreter, and a great appreciator of writers and arrangers. He’s one of the only artists that I can ever think of that when he performed, he would say who wrote the song, and who arranged the song too, which was remarkable. He had such an appreciation for them. But then Elvis didn’t write any songs either.

AVC: I wanted to talk about a few specific songs. You write about performing at the Troubadour and Leon Russell saying, “Well, that’s me done” after the performance. And the piano is a bit reminiscent of a Leon Russell song.

BT: Sure, sure.

AVC: Was that something you had in mind when you wrote the lyrics?

BT: No, no, absolutely not. You’re talking about “Song For You”?

AVC: Yes.

BT: No, that’s the one thing that made us realize that “Your Song” is something special, because there was no outside influence on it. You know with any artist, when they start in any sort of art form, whether it’s painting or whether it’s making movies or writing songs, you tend to emulate your heroes. You kind of lend a little bit from them. And I’ve done that in all facets. But the thing is, you get a point where you go, “Okay, I’ve got to find an original voice.” So a lot of the songs that we’d written in the early days, before “Your Song,” were kind of pastiches of people that were current at the time.

One of the first big hits that was out when Elton and I first got together was “Whiter Shade Of Pale,” by Procol Harum. And it was very esoteric and the lyrics were fanciful and didn’t really make any sense. But that was what people were doing back then, like Pink Floyd and Cream and whoever else—Jimi Hendrix, whatever. Those songs were all very pie-in-the-sky, tinges of psychedelia, what have you. People were emulating that, and so were we. I was drawing a lot of inspiration from fantasy novels, sci-fi, sci-fantasy. But the first song that we ever wrote that we kind of went, “Okay this is different, this is good,” and had kind of a folky edge to it was “Skyline Pigeon,” which was pretty good. It was fanciful, it was romantic. It was a really good song. And then along comes “Your Song,” and I think that’s when we went, “Okay, I think we found our own voice with this.”

AVC: My co-worker Mary Kate is from Philadelphia, so she wanted me to ask you about “Philadelphia Freedom.” You’ve said before you didn’t write it about tennis or patriotism or anything like that, so what did you write it about?

BT: Well, I didn’t. [Laughs] We were very good friends—still are—with Billie Jean King, and the Philadelphia Freedoms was a tennis team. Elton wanted to write something for her, but I said, “I ain’t writin’ a song about tennis. Because it’s not really rock n’ roll, man!” I mean, how do you write a song that’s serious about tennis? And at the same time that we were doing this, the Philadelphia sound was very, very prominent, so it made sense to incorporate that. But I have no recollection of why I wrote what I wrote. I just wanted to write something that was anthemic. It was actually more nationalistic than necessarily just for one town. It’s more about the American spirit than just Philadelphia. And I believe that Gene Page did that, who was a big arranger for all the Philly records. Philly records were huge at that time, so we wanted to do something that was a solution to not just the city, but was also kind of a national thing, and also bringing in the Philly sounds. But lyrical content—I can’t even remember the lyrics, which is not unusual for me. As I say in the book, I got three out of six questions on Jeopardy! on our songs wrong.

AVC: One song that I had kind of discovered while preparing for this was from your Honky Chateau album. You have this song called “I Think I’m Going To Kill Myself,” which just cracked me up because that’s something I say once a day.

BT: [Laughs] I think you’ve answered your own question there, really. Those things are just thrown off the cuff. We probably said the same thing back then, you know, “Ugh, I think I’m gonna kill myself.” It just a jokey thing about teenage angst, simple as that. There’s no deep, deep backstory. You just write those things.

AVC: I had kind of thought of that mindset as an internet-age thing, and to see a song from 1972—

BT: Exactly. You have to put yourself back there, but what’s good about that is you say it every day, well, we were saying it back then too! Everything old is new again.

AVC: Maybe my favorite of your songs is “The Bitch Is Back.” I think I had read that your wife at the time had said it about Elton?

BT: I think Elton had just gotten back from a U.S. tour or something and was in a cranky mood and we were all at the house and I think she may have coined it. I can’t remember now, but somebody said it anyway. Just joking, “Oh, the bitch is back.” It’s something somebody said, so you pick up on that. Again, it’s something I said in the book, I make copious notes all the time. I did back then certainly. I’d hear a phrase like that and I’d go, “That sounds like a song.” And when you hear something like that, you know it’s not going to be a ballad. You know it’s going to be a sort of straight-ahead rock n’ roll song.

You know, people always ask me, “When you give Elton a lyric, do you have an idea of what it should sound like?” And I say, well sometimes the title alone dictates what kind of song it’s going to be. You know, if you write “Saturday Night’s Alright For Fighting,” it’s not going to be a delicate ballad. And the same way, if you write, “Don’t Let The Sun Go Down On Me,” you know it’s not going to be a full-tilt rocker either. Even with “Philadelphia Freedom.” You read that and go, “This sounds anthemic.”

AVC: Are there any songs you’ve gotten sick of hearing after 30, 40 years?

BT: No, I don’t get sick of them. If they stop playing them, I don’t like that. [Laughs] I’m not going to get sick of hearing them. I’m not sick of any of them at all. I could probably do without hearing “Crocodile Rock” or “Don’t Go Breaking My Heart” on a tape loop 24 hours a day, but they’re great throwaway pop songs, and we’ve written those as many as we’ve written those with longevity. Our songs keep coming back, which is really very emotionally satisfying because it seems like they have a timeless quality to them.