Better late than never: Falling in love with Yankee Hotel Foxtrot on its 20th anniversary

Two decades later, the record feels ageless, with wrenching and brutally honest lyrics that still ring true

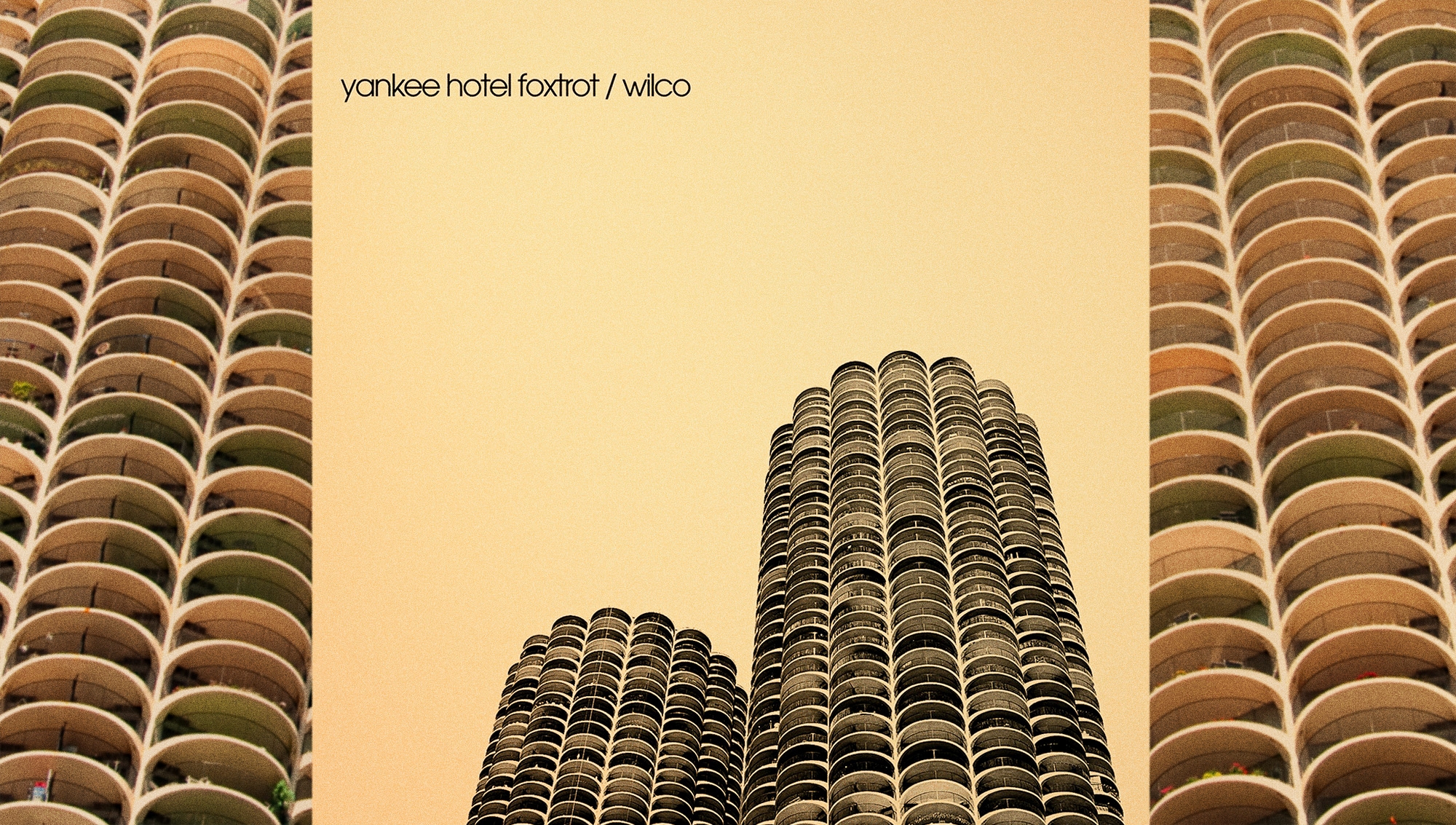

Image: Graphic: Karl Gustafson

In Better Late Than Never, A.V. Club writers attempt to fill the gaps in their overall pop culture knowledge and experience.

There’s an episode in the first season of Joe Pera Talks With You where the fictionalized version of “Joe Pera” listens to The Who’s classic “Baba O’Riley” for the first time. He becomes so enamored with the song that he declares his love for it during the church announcements. He calls in radio stations asking them to play it for him, dancing erratically around the room, like he’s never heard a better piece of music; at one point, he even invites the pizza delivery guy to join in on the fun. When I watched that episode, I wondered if I’d ever feel as elated discovering an old-yet-new-to-me musical piece. That moment came when I finally listened to Wilco’s Yankee Hotel Foxtrot in the summer of 2021.

It’s as surprising for me as it might be to any Wilco fans reading this that it took me this long to listen to Yankee Hotel Foxtrot. Wilco is a band to whom people I’ve met over the years have spoken at length about having a strong emotional connection—and, to a certain degree, it worried me to think I might not connect with its music on the same level. But I found the record at a serendipitous time: A month prior to listening to it, I’d experienced a breakup. Things had ended abruptly, marred by miscommunication, unprocessed feelings, and anxiety.

The record—written by Jeff Tweedy in part about miscommunication and the struggle of processing emotions—feels ageless after twenty years, with lyrics that feel like a glimpse inside the mind of someone who cannot verbalize their feelings. But to reduce Tweedy’s thoughtful, poetic lyrics to someone who is simply incapable of having a secure, healthy relationship would be a disservice—no matter how tempting it is.

Wilco’s fourth record, Yankee Hotel Foxtrot, was borne in a pivotal moment for the band. Drummer Ken Coomer and Tweedy weren’t seeing eye-to-eye in the band’s direction, with enough friction to have him replaced with Glenn Kotche in the midst of planning the LP. The band was coming off the heels of its critically acclaimed 1999 record, Summerteeth, but wanted to try something new. Thus emerged Yankee Hotel Foxtrot, an album that opened possibilities for sonic experimentation that Wilco hadn’t yet attempted. That gamble of creating something different paid off.

Upon first listen, it was cathartic to hear the opening track, “I Am Trying To Break Your Heart,” where Tweedy sings about conflicted feelings in a tumultuous relationship. In the lyrics, it’s clear the couple cares about each other, unable to fully break free from a dynamic that doesn’t work, but he knows he’ll hurt his partner in the end.

“What was I thinking when I said hello?”, questions Tweedy, carrying the burden of knowing he broke his partner’s heart. But he’s torn between the indecision of closing the chapter after an on-and-off relationship, or sticking around because there’s still some emotional attachment: “What was I thinking when I let go of you?”

The confusion of his emotions is matched with the instrumentation, as Wilco combines busy sounds, including synths, piano, bells, percussion, and guitar. It almost feels like you don’t know where to focus your emotions. It’s overwhelming, yet melodic. It’s disorienting, yet oddly comforting—just like the dynamic that Tweedy sings about.

His lyrics expertly capture conflicting feelings, often seeming like he’s attempting to make sense of them in real time. That sentiment is expressed in “I’m The Man Who Loves You,” with Tweedy struggling to find a way to understand his thoughts and put them into words, allowing him to explain to his partner how he feels:

All I can see is black and white and white and pink with blades of blue /

that lay between the words I think on a page I was meaning to send to you /

I couldn’t tell if it’d bring my heart the way I wanted when I started /

writing this letter to you

Can’t he just hold his partner’s hand and show her how much he cares and loves her, rather than go through the brain-wracking process of putting those emotions into words? It’s a relatable feeling.

The pacing of the song is arranged in a way that sounds like the way scattered thoughts trickle in, with a rapid, thumping beat. You can tell he knows how he feels deep down: It should be as simple as that. But the lyrics also come from an anxious source, that understands that love isn’t clear cut. It’s a sentiment delved into throughout much of the record, including songs like “Radio Cure” and fan-favorite “Poor Places.”

“Radio Cure” is gentle and entrancing, with synths that replicate the sound of radio airwaves. But it addresses a more concrete difficulty in the relationship: distance. It can be interpreted as metaphorical distance, with Tweedy keeping his partner at arm’s length, as he sings, “Oh, distance has no way of making love understandable.” But it also feels literal and very personal, since Tweedy openly had marital struggles after being on the road so much for Summerteeth. It’s a reminder of what happens when a couple is driven apart due to work or other commitments, incapable of spending time understanding each other and giving proper affection.

In ”Poor Places,” similarly, Tweedy addresses the effects of depression, and how mental health struggles create a disconnect in his relationship. There are references to depending on alcohol to cope. He wants to be there for his partner (“I really want to see you tonight”) but it’s not possible because of that forced distance. Again, “Poor Places” takes a more pared-down approach; the synths are still busy, and we hear the voice from the radio, repeating the album’s name. Plus, the inclusion of the “Yankee Hotel Foxtrot” recording hints at this track being the album’s thesis: There are limitations that are simply out of his control, disconnecting Tweedy’s desires from the actions he takes.

But the most emotionally charged track is closer “Reservations.” It feels like the kind of intimate, quiet argument a couple would have about one partner’s inability to commit. “How can I convince you it’s me I don’t like / and not be so indifferent to the look in your eyes / when I’ve always been distant and I’ve always told lies for love” is such a vulnerable admittance. It’s easy to succumb to anxiety—especially when a relationship hits roadblocks—and have those reservations.

What gives “Reservations” a particularly heavy quality is how the music matches the intensity of the lyrics. The echoing synths accompanied by piano can shatter you to your core. The haunting instrumental interlude adds even more gravitas. Closing the record, it’s understood that part of the reason why there’s so much miscommunication and confusion in the narrative told on Yankee Hotel Foxtrot is because there’s so much bubbling under the surface for Tweedy’s lyrical voice. Love is messy. It’s a gamble. It’s difficult to show your most vulnerable self to someone, exposing the ugly parts hidden inside.

Catching Wilco perform Yankee Hotel Foxtrot on the band’s anniversary tour, I found myself moved to tears when it performed “Reservations.” Even the rowdiest audience members fell into deep silence, soaking in the weight of Tweedy’s words.

But Yankee Hotel Foxtrot isn’t all about those deeply emotional conversations about relationship dynamics. There’s the lyrically ambiguous classic “Jesus Etc.”, that despite being written before 9/11, eerily contains the line, “Tall buildings shake / voices escape singing sad sad songs / tuned to chords strung down your cheeks / bitter melodies turning your orbit around.” Its melancholic imagery is paired with dazzling string arrangements; it’s easy to see why this is one of the band’s biggest songs.

“Kamera” is another standout. It doesn’t feel as lyrically heavy as much of the rest of the album, but still hints at Tweedy’s distress, as he sings, “Phone my family / tell ’em I’m lost on the sidewalk /and no, it’s not okay” in the chorus. But those sentiments are disguised with lively guitar and twinkling synths.

Then there’s “Heavy Metal Drummer,” feeling almost like an outlier on the album. While most of the songs take a gentler approach, “Heavy Metal Drummer” is poppy and effervescent, with Tweedy yearning for the days of his youth, playing KISS covers, “beautiful and stoned.” It may not be the best song Tweedy’s ever written, but there’s something infectious about its sound, making you want to stay in that moment of energizing nostalgia before having to face the current harsh reality.

The beauty of Yankee Hotel Foxtrot, I’m realizing, is that while there are so many Wilco fans who have a strong attachment to the story of making the record, you don’t need to know details of Jim O’Rourke’s production, or the late Jay Bennett’s contributions to the compositions, to love and understand it. Tweedy’s writing for himself, but the lyrics stand the test of time because they resonate so strongly with anyone who’s struggled to vocalize their emotions as they grapple with depression, anxiety, and self-doubt. And beyond the lyrics, it has a very distinct, alluring sound that makes you want to stay longer with the record. It can be played on loop without it being bothersome in the slightest.

Yankee Hotel Foxtrot almost didn’t get released, between Reprise Records being unhappy with the record, and Wilco initially choosing September 11, 2001 as its premiere date. What would’ve happened if Tweedy hadn’t taken matters into his own hands, self-releasing the album in the midst of finding a new label? It’s difficult to think where the group, or its fans, would be without Yankee Hotel Foxtrot, regardless of when it entered our lives.

A couple of rows ahead of me stood a father with his pre-adolescent son, embracing him as they watched the show. I thought about the gift of passing on such a powerful record through generations. Yankee Hotel Foxtrot is an album that seemingly finds us when we need it the most. Every fan has a different story of their emotional attachment to it—but the impact is the same for all.