Betting it all on 311

It’s been 16 years since 311 last had a hit, but they’ve kept busy. In the time since their lovers alt-rock take on The Cure’s “Lovesong” crossed over, the quintet has established a biennial Caribbean cruise, licensed their name to a number of craft beers, and created strains of marijuana. Just last year, they launched their own line of CBD gels, drops, and pet-relief products. They’ve also released six albums; all but one of them—2019’s Voyager—debuted in Billboard’s top ten. Somewhere after the last fade-out of “Amber” from modern-rock radio, the band became a five-sided figurehead around which a large, robust, and active base of fans congregate. These are people who hear “I cannot handle all you negative vibe merchants, is that all you have in you, perchance?” as instructions for living the good life.

Their charming-ish holiday—March 11, a.k.a. 3/11—is now a major destination event held on even-numbered years in tourist-friendly cities like Las Vegas and New Orleans. 311 fans (many of whom call themselves “the Excitables”) descend en masse clad in their favorite pro teams’ jerseys with “311” stitched into the number plate, and the band plays marathon sets; 2004’s topped out at 68 songs in a little over four hours. This year, for the band’s 30th anniversary, they took over the Park MGM in Las Vegas, playing 102 songs over three nights with no repeats. If you want more beats for your buck, you’re in luck.

For years, co-singer Nick Hexum would end 311 concerts by saying, “Stay positive and love your life.” In 1997, he dropped the phrase into the song “Jupiter,” canonizing it as something like the entirety of the law and the prophets for Excitable disciples.

This year, for the band’s 30th anniversary, 311 took over the Park MGM in Las Vegas, playing 102 songs over three nights with no repeats.

“It came from a warm wish of what I would want on my tombstone,” Hexum told The A.V. Club a few weeks before 311 Day 2020. “It’s what I would want people to take away if I could sum it up in one sentence.” If you’re the kind of person who still has opinions about bands whose popularity peaked 20 years ago, the degree to which you agree with that statement probably reflects how you feel about 311’s music today. There’s a cheery simplicity to the phrase that feels grating in light of the ever-widening gyre.

But it’s this worldview that has made 311 one of the oldest active bands still composed of its original members. The handful who have been around longer (ZZ Top, U2, Radiohead, De La Soul) have enjoyed critical praise and industry support that 311 never has or will. They have never been nominated for a Grammy. They’ve never come anywhere near the Pazz & Jop; The A.V. Club once went out of its way to call 311 “soulless quasi-funk” in a review of another band. They will never be inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame. There will be no well-regarded Netflix documentary. They do not change their set lists up night after night, and they do not jam. They’re never going to die, as I know all too well. So I went to Vegas to learn how to live.

The Park Theater is a 6,000-capacity rectangle arranged so the long side abuts the stage; the farthest-back seats seem like they’re right on top of the band, making it feel remarkably intimate for a venue of its size. In normal circumstances, this would be to our advantage as a crowd. But today is March 11, 2020. Earlier this evening, the NBA canceled the remainder of its season following Rudy Gobert’s positive test for COVID-19. A few moments later, Tom Hanks and Rita Wilson announce that they’ve been infected. A few moments after that, the doors open, and 311 fans begin to stream into the venue. My tickets are on the floor. General admission. The pit.

If anyone in the crowd is worried about their physical proximity to a mass of people, they don’t show it. Gen Xers and older millennials file into place in front of the stage, hopping from foot to foot in anticipation. One guy whose bald spot and hairline are in a race to the middle of his head is telling a fresh-faced kid who looks to be in his mid-20s how hype 311 shows were in the ’90s. His excitement is real, but it feels like he’s managing expectations. Two nights from now, I’ll see a bearded guy with wavy, shoulder-length hair in flowing robes decked with marijuana leaves: Weed Jesus, someone explains. He gives me a polite, baked smile.

Today is March 11, 2020. Earlier this evening, the NBA canceled the remainder of its season. A few moments later, Tom Hanks and Rita Wilson announce they’ve been infected. A few moments after that, the doors open, and fans stream into the venue. My tickets are on the floor. General admission. The pit.

The crowd chatters about how the band might structure these three concerts. The most popular guess is that they’ll devote each night to 10 years of 311 history: three decades, three nights. Every single person who floats this idea immediately says they hope this isn’t what happens. There is a consensus, at least among the people I’m near, that half of the second night and all of the third night would be a drag. I’m inclined to agree, but it’s strange to hear the band’s biggest fans, all of whom shelled out at least $300 to be here, write off fully half of their discography. One guy says he hopes they play “Down” first, just to get it out of the way.

Instead, the set opens with “Freak Out,” a reliably charging standard from 1992’s Music. Instantly, joints appear. Small pipes are liberated from their hiding places and packed, passed, and gladly accepted—virus, I guess, be damned. All around me, the crowd is bouncing as Hexum and Doug “S.A.” Martinez’s vocals cross one another before they come together and command us to “Jump to the beat, then J-U-M-P.” I suspect it’s extremely unwise to be jumping around in a packed crowd, but it’s impossible to stand still in a group of people who are in perpetual motion without getting bowled over or looking like an asshole, so I jump, too.

When the band launches into “Beautiful Disaster,” I take it as a sign that I should dig out the joint of the same name that I picked up at a dispensary off The Strip and see what it has to teach me. I take three or four puffs, smirk to myself, then take a couple more. And I am very stoned. As the band sails into the long, contemplative intro of “Let The Cards Fall,” everyone passes around decks of playing cards, and when the build finally breaks into a charge for the opening verse, everyone throws their cards in the air. Jacks, fours, aces flutter around me, and I watch as they drift through the theater, smiling. It feels good to be here, in this peacefully worked-up crowd, and to glide on as Hexum raps about following my bliss every day. I wander back in the crowd, trying to catch my breath and create a little space for myself, and I hear, clear as a bell, the voices of everyone around me singing along to the chorus of “Do You Right,” not loudly, but clearly, the way you do in church—and then it hits me.

I am a month or so shy of my 17th birthday, and the mushroom tea is treating me kindly. I turn around to watch the balcony of the State Palace Theatre, a mushy wedding cake of a venue on Canal Street in New Orleans, as it seems to bounce along with the crowd. We almost didn’t get this concert: The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 were only a few weeks earlier, imperiling our right to do this, to be out having fun, doing teenager shit. All around me, I hear the voices of people singing in a way that seems to replace the actual sound being made by 311 guitarist Tim Mahoney, so the simple three-note shuffle that is the intro and break in “Do You Right” is all human voices. I turn back to make sure and, yes, Tim is right there, playing us. This is my fourth 311 concert. The first was in the same room, on March 11, 2000. By the time I finish high school, I’ll lose count of how many times I’ve seen them.

For middle-school boys in Lafayette, Louisiana, in the mid-1990s, heaviness was the most valuable of musical currencies. Based on the way I’d heard people talking about 311, I assumed they made Pantera look like R.E.M. I was in sixth grade, ready to trim my emotional baby fat, so I made it a point of tracking them down as soon as possible. Sometime in 1996, when I finally cracked open a copy of 311, a.k.a. the Blue Album, and dropped it in my CD player, I was stunned by Martinez’s opening salvo in “Down”: “Chill!” Chill?

I got over my disappointment at being peer-pressured into liking something so upbeat. Then I got extremely over it. The connection I had with 311 felt cellular. Hearing them activated something in me that had to that point been dormant, a strange and private sense of self that I could only access through their music. I recognized that this was for me in a way that nothing else I’d ever before experienced had been for me. 311 was the first band I ever felt was mine.

Nick Hexum knows the feeling. He says The Clash rolled through Omaha when he was 14. It was 1984, the waning years; Topper Headon and Mick Jones were already out of the band, which was then two years into touring Combat Rock. Nevertheless, Hexum told me, “When Joe Strummer came out with his blond mohawk, I literally got weak in the knees. I was overwhelmed. I’d been obsessing on this moment for so long. He came out and just ripped into ‘London Calling,’ and there were tears streaming down my face.” There were other formative shows, but they were all mainstream, middle-of-the-road acts like Hall & Oates and Men At Work. The underground wasn’t coming to Omaha yet; seeing The Clash at the nadir of its cool was all it took to change Hexum’s life.

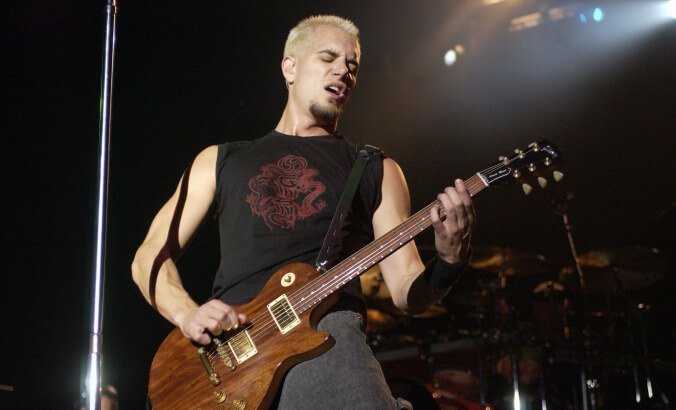

Strummer’s omnivorous taste—and, by 1984, his radio-friendly translations of edgier genres—would inform Hexum’s approach to songwriting. When 311 emerged with Music, they were already figuring out how to marry the heavy energy of chunky Midwestern rock with the rubbery rhythms of funk. What instantly separated them from the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Jane’s Addiction, and other punk-funk bands of that era was the particular genius of Mahoney, who was an equal devotee of diamond-sharp jazz players like Pat Metheny, the flamethrowing of Dimebag Darrell, and the hairpin turns of James Brown’s legendary guitarist Jimmy Nolen. Rather than grunt his way through the drop-D punishment riffs favored by the rap-metal bands 311 was sometimes lumped in with, Mahoney played rhythm guitar in essentially the same way George Porter of The Meters played bass: groove above all else. Even at its most aggressive, 311’s music is inviting and open; the emphasis on groove compels you to move your body in tandem with the rhythm, to step with it. “Nod your head to this,” Hexum commands in “Applied Science,” and it’s impossible not to, no matter how you feel about the song. It’s the communal experience he and Martinez were rapping about come to life through guitars.

As a music critic, I’m not blind to the many, many faults in 311’s music… But it’s equally dishonest to ignore the things that 311 did and occasionally still do that work for me.

So it’s something of a surprise that their best record is also their most insular. When it was released in 1997, Transistor jammed 21 songs onto a single CD, filling it to the absolute margins. It’s full of extended jams and starlit melodies shrouded in rich weed smoke, and it was considered a flop after the chart-storming success of the Blue Album. 311’s recorded understanding of reggae often comes across as watered down and influenced more by The Police than “Police And Thieves,” but Transistor uses their twinned devotion to Jamaican music and classic rock to profound effect. They understood that the imperial gases of dub could fill the massive sound stages of Dark Side Of The Moon and float them far beyond the band’s Midwestern roots. Despite what the band and their fans claim for it, it’s not a dub record, but it does use the principles of space, repetition, and deletion to glide into the galaxy in a way few, if any, radio-oriented rock albums have ever done. They were in awe of where it brought them, and the sights they share on “Inner Light Spectrum,” which builds into a muffled groove of distant cowbells and e-bowed guitar, or “Running,” which nicks an intro from Mahavishnu Orchestra and a solo from Jerry Garcia, are as arresting as the view of Earth from space.

As a music critic, I’m not blind to the many, many faults in 311’s music: the faux swagger, the annoying slap-bass, the perpetually reverberating pock of the snare drum Chad Sexton insists on tuning extremely high. [Which is not, as originally identified, a piccolo snare—Ed.] Even as a megafan, I couldn’t hear a line like “If dealing with punks was school, I’d have a Harvard degree” without wincing. But it’s equally dishonest to ignore the things that 311 did and occasionally still do that work for me.

Since moving to Los Angeles in 2016, I’ll put on Music or Grassroots every once in a while, just to see how it makes me feel. My hope is always to discover that, with time and perspective, 311 has secretly become great. I am always let down. But I’m struck by the fact that they set the musical priorities that have guided my listening to this day: the primacy of groove, the importance of empty space, the conviction that music is for the body as much as the mind, and the easy transit of sound and sensation between those two poles. Other bands could have given me all that, and plenty have. But 311 got there first.

By the time I wander over to the Park MGM on Thursday afternoon, people are streaming up and down Las Vegas Boulevard, some with yardstick-length daiquiris in hand. As far as I know, night two of 311 Day 2020 is on. The clerk at CVS who rings up my tallboy of Pacifico tells me it’ll kill the coronavirus: “Alcohol for the throat, not for the hands.”

I plant myself at the very back of the floor when it becomes increasingly clear that the band will not be addressing the pandemic or encouraging us to make a little room in the pit. The closest they come to referencing it is Hexum thanking the crowd for being there in spite of everything without specifically saying anything about the virus, which feels painfully irresponsible. (When asked about its decision to move forward with 311 Day 2020, the band’s management team said in a statement: “We relied on the official recommendations of state and local authorities in deciding to proceed with the shows, including the statements of the governor of Nevada, the mayor of Las Vegas, and the Nevada health commissioner on March 12.”) It’s impossible not to wonder whether the as-yet unstated need to stay positive and love our lives precludes looking at the situation with clear eyes.

Nothing the band does sounds right. “Sick Tight,” a song that sounds exactly like and is as good as the title implies, reminds me just how corny they allow themselves to get: “311, you want to get next to them / My name is Nick H-E-X-U-M,” goes one especially rough couplet, while Martinez soberly proclaims, “Houston, we have a problem, all this TV has made us dumb” in “Other Side Of Things,” a song written 10 years after Apollo 13 and 20 after Amusing Ourselves To Death. A cover of Bob Marley’s “Lively Up Yourself” does not inspire me to do so.

Which isn’t to say there aren’t highlights. They extend the intro to the simmering jazz-funk of “8:16 a.m.” and loosen the song up a bit, then take their time spinning into a gorgeous “Inner Light Spectrum.” “Use Of Time,” a Transistor standout that coats Pink Floyd’s “Wish You Were Here” in dubby dust, gives way to a five-minute drone, of all things, which starts out soft and dark and is shot through with hot lines from Mahoney. An interlude with Hexum’s 10-year-old daughter, Echo, playing piano to her dad’s guitar accompaniment—and the full-throated chant she gets from the crowd in response—is a genuinely touching reminder of how deeply the fans and the band identify with one another. I’ve never felt more disassociated from the small but noisy part of me that still feels some sense of loyalty to this band. I get the sense that everyone else feels like they’ve gradually grown old with one another and is committed to hanging on for as long as they can.

Nathan Allen says 311 changed his life, and he’s so convinced of it, I find it impossible not to believe him. Like many of the older fans I meet, he was a devotee of Nirvana and Rage Against The Machine in the early ’90s, but the more time he spent with 311, the more things began to shift. “I got tired of negativity,” he says. He shows me the 311 tattoo on his forearm and makes a point of saying he’s not the kind of guy who would normally get a band’s logo stamped on his body; 311 just had that kind of effect on him. “I started realizing how much poison that outside energy can bring to your life, and the more you surround yourself with good energy, the more that gives back to you, and it’s just a snowball effect.”

The feeling of being out of step with the prevailing cynicism has been part of 311’s story from the very beginning. In the late ’80s, Hexum, who had graduated high school early, moved to L.A., but was disillusioned by the bourbon-fueled excess of the Sunset Strip. When 311 got together in 1990, he tells me, “We wanted to be outside, we liked reggae music, we wanted to have more joy in our lives.” Across their 30-year discography, he’s rarely felt the need to talk shit; a not-quite-comprehensive list of people who make negative appearances in 311 songs includes “mean people,” a house sitter who racked up a massive phone bill while the band was on tour, and, most famously, the naysayers. The song “Hostile Apostle,” from From Chaos, takes to task rockers whose “skulls and piercings and will to destroy” lead kids down the wrong path, one marked by “one emotion, one tempo, and no real feeling.” The issue isn’t anger, in other words, or darkness, but in building one’s entire life around the “poison” Nathan Allen works to avoid—the monotony of cynicism is as dull and damaging as a beat that never changes.

Something Hexum said in our interview has stuck with me. I asked him why he thinks people give 311 fans so much shit for their relentless positivity. He sighed, then said that it had always been important to him that 311 be sincere above all else, and that this sometimes makes people uncomfortable. “I remember Rolling Stone or somebody, when they reviewed the Blue Album, they called ‘Misdirected Hostility’ ‘an anti-depth rant,’ as if to say, if you’re negative, you have depth, but if you’re positive, then you’re shallow. And I’m like, ‘I’m talking about my inner struggle to try to find things I like about this life, and not just give in to the call of the void.’”

Near the very end of night three, the band plays a graceful version of “1, 2, 3,” a slow-mo reggae tune draped with a George Harrison guitar lead. When Hexum wrote it in 1994, he was responding in part to what he saw as the nihilism of the time, and in part to the anxiety of feeling like you need to belong to your era. “It’s all right to feel good,” goes the chorus. “It’s all right for nothing to be wrong.” Hexum sings it like a lullaby, like he’s aware of how brittle a foundation such good feelings can be, even as he was just beginning to build his life atop them.

This is the implied message behind so much of 311’s music, and it’s the reason why it remains vital for so many people. It is immensely difficult to stay positive in the best of times, and the struggle between the desire for life to be good and the acknowledgment of the many ways in which it’s not is fundamental to what it means to be alive. Trying to stay positive can feel intellectually dishonest: It suggests you haven’t considered all the facts. But in a world of limitless facts, it feels equally dishonest to discount the many good things that still exist. “They’re very specifically not about blind positivity,” a fan named Saralyn Bliss tells me. “It’s not about trying to pretend like it’s all rainbows and kitty cats. It’s about real life.”

Being given the permission to wholeheartedly accept the good things in your life, whatever you understand them to be, is a powerful thing. But when Nathan Allen tells me that his refusal to live his life in fear kept him from skipping 311 Day out of concern for the pandemic, I get hung up on the idea that looking into the sun, even for just a few minutes, blots out your ability to see the rest of the world clearly. Still, the broader ethical implications of being a vector for the virus notwithstanding, I’m envious of Allen’s general demeanor—and Bliss’, and Hexum’s—which at its core is, You don’t have to let valid criticism destroy the things you love. Throughout my time in Las Vegas, and in the weeks before and after, I feel like I, too, have wandered sun-drunk into the desert.

Being a 311 fan is not terribly different from going to church. The fact that it seems, from an outside perspective, to be totally out of touch is precisely what makes it so necessary for the people who are there.

There is something a little ridiculous about 311, a silly anomaly in five guys from Omaha who still have traces of Midwestern accents after spending 30 years in California, pursuing and evangelizing an island-tinged form of optimism. Unlike any other band I can think of, 311 seems to mean more in their twilight years than they did during the boom. The music is diminishing, as most will concede, but their continued existence, their willingness to plow through hammy rap-rock in the name of bringing their people together, and Hexum’s ability to shrug off his cloak of consummate professionalism to sing a song as utterly idiotic as “Juan Bond,” gives their fans a space to slip into their own weirdest, most-at-ease selves. The self that can’t show up at a nonprofit or a law firm, yes, but also the self that knows it lives in a world of cynicism, anger, and fear, and thus has to keep its head down. The self that is subject to those very same things, and which, as a result, needs to be perpetually renewed. In this way, being a 311 fan—and being in 311—is not terribly different from going to church. The fact that it seems, from an outside perspective, to be totally out of touch is precisely what makes it so necessary for the people who are there.

As I stumble through the casino floor late on Friday night, nobody else looks tired. In the coming week, California and New York will enter quarantine, and the world will begin to contract. These are the waning moments of free American life. I pass middle-aged women in matching Atlanta Falcons jerseys, both numbered 311. Dudes in backwards caps and knee-length plaid shorts. Guys in tank tops revealing greening tattoos. Girls in bell-bottoms with casino-carpet patterns. The “my ma gave me a dollar and dropped me off at the Park & Ride” suburban rocker crowd. Ed Kowalczyk types. The very last person I notice, before I leave the Park MGM in search of a slice of pizza and clean air and wide-open spaces, walks past me with a stoned and sanctified grin. Weed Jesus is heading back into the crowd.