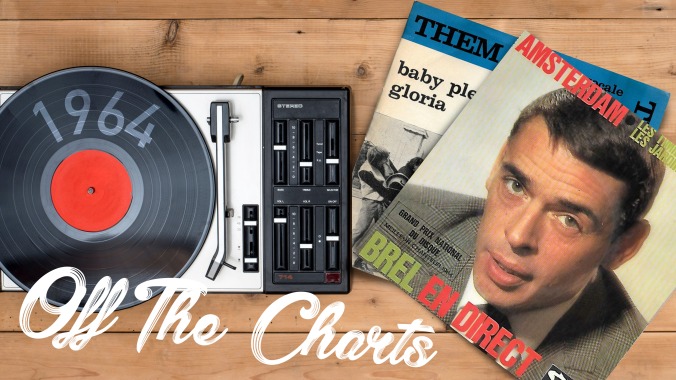

Beyond The Beatles: The protopunks, French classics, and ska pioneers of 1964

Image: Graphic: Nicole Antonuccio

The Year: 1964

Billboard Hot 100’s Top 20 Songs Of 1964

1. The Beatles, “I Want To Hold Your Hand”

2. The Beatles, “She Loves You”

3. Louis Armstrong, “Hello, Dolly!”

4. Roy Orbison, “Oh, Pretty Woman”

5. The Beach Boys, “I Get Around”

6. Dean Martin, “Everybody Loves Somebody”

7. Mary Wells, “My Guy”

8. Gale Garnett, “We’ll Sing In The Sunshine”

9. J. Frank Wilson & The Cavaliers, “Last Kiss”

10. The Supremes, “Where Did Our Love Go”

11. Barbra Streisand, “People”

12. Al Hirt, “Java”

13. The Beatles, “A Hard Day’s Night”

14. The Beatles, “Love Me Do”

15. Manfred Mann, “Do Wah Diddy Diddy”

16. The Beatles, “Please Please Me”

17. Martha And The Vandellas, “Dancing In The Street”

18. Billy J. Kramer & The Dakotas, “Little Children”

19. The Ray Charles Singers, “Love Me With All Your Heart (Cuando Calienta El Sol)”

20. The Drifters, “Under The Boardwalk”

“They’ve got their own groups. What are we going to give them that they don’t already have?”

That’s what Paul McCartney reportedly told journalists aboard The Beatles’ first flight from London to New York, just hours before being greeted by thousands of screaming fans at John F. Kennedy airport and infecting America with Beatlemania. His anxiety was understandable. After all, what were the odds a few pasty British dudes could make it in America, the land that birthed rock ’n’ roll and the artists whose music made The Beatles what they are? Record executives seemed to echo the same doubts. Despite their success in the U.K. and Europe, Capitol turned down not one but two opportunities to introduce The Beatles to the U.S. in 1963. That honor fell instead to two smaller labels, and the band failed to crack the charts. Capitol didn’t give in and pick up “I Want To Hold Your Hand” until the band was booked for its fateful appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show and came equipped with its own free nationwide exposure. That’s not exactly a vote of confidence.

It’s safe to say things worked out pretty well for Mr. McCartney and his buddies, though. 1964 will forever be remembered as the year the Fab Four dominated American airwaves and shook rock ’n’ roll from its slumber. Paul was seriously overselling the state of mainstream American rock. As far as the charts were concerned, it’s true the fledgling genre fell into a sort of dark ages for the five years—nearly to the day—between “The Day The Music Died” and The Beatles’ arrival. Surf rockers twanged out the occasional hit, Dion and Del Shannon scored with singles that somehow sounded like throwbacks to a heyday that had barely passed, and The Beach Boys worked their way up the charts, eventually landing the top single of 1963 with “Surfin’ USA.” But beyond that, it was slim pickings. Country, Motown, girl groups, and crooners named Bobby dominated the airwaves. The Beatles’ conquest of 1964 marked a turning point, a hard delineation after which rock bands stormed the charts once again.

But the British Invasion is just one of the many important musical stories coming out of 1964. Rock may have lost its nationwide megastars during those five dark years, but it spent that time percolating in influential regional scenes. The prickly fruits of that gestation finally matured into garage rock and its gritty, blues-obsessed punk forerunners, like Tacoma’s The Sonics and Boston’s The Rockin’ Ramrods. In New York, Simon & Garfunkel stumbled their way toward stardom, and a satirical dance song brought Lou Reed and John Cale together, giving birth to a tandem and a style of guitar playing that would change rock history. In France, a teenage yé-yé icon came into her own and two of chanson’s greatest singers released masterworks. In England, two hard-edged bands missed the memo about that whole invasion thing but forged paths of their own. And that’s not even half of the important, impressive, and overlooked tracks we’ll be exploring in our alternate top 20 for 1964.

Note: Not all of this edition’s songs are available on Spotify.

Barbara, “Nantes”

Barbara, née Monique Serf, got her start in the 1950s singing Jacques Brel and George Brassens songs in small cabarets around Paris and Brussels. And though she released several albums of these interpretations, it wasn’t until she finally put out a collection of her own material, 1964’s Barbara Chante Barbara, that she began to take her place among these towering figures of French song. “Nantes” is the centerpiece to Chante Barbara, recounting with great poetry the singer’s unsuccessful attempt to see her long-absent father in his final hour. Like the best of French chanson, the song is absolutely gutting, with a wistful, lilting melody conveying the push-pull of emotions Barbara felt for her father, whose abuse and abandonment would loom over her entire three-decade catalog. By the end of ’64, Barbara was asked to open for Brassens himself at Paris music hall Bobino, and by the venue’s following season, she was headlining her own run of sold-out shows. [Kelsey J. Waite]

Jacques Brel, “Amsterdam”

There’s no hard numbers on this, but it’s probably safe to say a lot of people (in the English-speaking world, anyway) came to Jacques Brel’s “Amsterdam” through one of two paths: the musical revue Jacques Brel Is Alive And Well And Living In Paris from 1968, and David Bowie’s translated cover of it, first released as a B-side to the “Sorrow” single from September 1973. (There are a number of other cover iterations, including one by Scott Walker in the late ’60s.) But Brel’s original version has plenty of fans on its own, the spare and poetic tale of sailors on shore leave in the Dutch city boasting a repetitive and simple (but enormously effective) melody, rolling with the rhythm of a sea shanty—accordion and all—but told with the vibe of a Parisian salon at 3 a.m. Brel never released a studio version of the song, instead leaving the live version found as the lead track on Enregistrement Public à l’Olympia 1964 his only document of it. [Alex McLevy]

Butlers, “She Tried To Kiss Me (All I Could Do Was Run)”

Partially in thanks to the guidance and friendship of Marvin Gaye, Frankie Beverly finally reached national fame in the ’70s as the charismatic lead singer of Maze. Before that, he spent his teenage years bouncing between short-lived doo-wop groups, eventually founding The Butlers at the age of 17 and making his first recordings. The band, which would survive into the ’70s and eventually evolve into the smooth soul of Maze after relocating from Philadelphia to San Francisco, debuted with its hottest single of all, “She Tried To Kiss Me (All I Could Do Was Run).” Beverly’s doo-wop roots are at the song’s heart, but they’re buried under a thick wall of raw, clattering snare drum. That element alone transforms what would’ve been a fine upbeat doo-wop tune into a breakneck Northern soul classic. [Matt Gerardi]

The Debs, “Danger Ahead”

The British hipsters who drove the Northern soul boom of the late ’60s and early ’70s fetishized rarity as much as today’s vinyl-worshipping Brooklynites, which helps explain how ultra-obscure girl group The Debs became a favorite at Northern English soul nights. Released on the independent label Double-L Records, “Danger Ahead” was produced by ex-Motown producer Bob Bateman, who by that time had moved to New York to work with Capitol Records and Wilson Pickett. That accounts for the clean-yet-soulful Detroit sound of this midtempo number, co-written by the late James Shaw—better known on the Atlanta scene by his stage name, The Mighty Hannibal. [Katie Rife]

The Primitives, “The Ostrich”

Lou Reed was cranking out future cut-outs when this riff on fleeting dance crazes—with its tongue-in-cheek, head-burying instructions—caught the ear of his Pickwick Records bosses. “The Ostrich” didn’t impress the band recruited to record the song, but Reed’s decision to play it on six strings all tuned to D made an impression on one of the hired hands: Welsh expat John Cale. Their thudding, screeching single was all but immediately grounded, but a creative partnership was just taking flight. As with most things involving The Velvet Underground, the impact of “The Ostrich” was its afterlife: in the “do it do it do it” ad libs it handed down to “Sister Ray,” and the namesake for the idiosyncratic tuning that provided the drone of “Venus In Furs” and “All Tomorrow’s Parties.” [Erik Adams]

Prince Buster, “Al Capone”

What Al Pacino in Scarface was to gangster rappers of the ’90s, Al Capone was to Jamaican musicians of the 1960s. With the sound of gunshots and screeching tires, ska pioneer Prince Buster pays tribute to the quintessential Chicago gangster on a (mostly) instrumental track that sprinkles scat-inspired vocals over scratchy guitars, bouncy bass, and jazzy horns. The rhythmic vocal style Prince Buster and his fellow emcees used to keep the party going at the “sound system” street parties where songs like “Al Capone” got most of their play—at the time, “respectable” Jamaican radio stations played exclusively foreign music—not only played a key role in the development of the offbeat rhythms of ska, but they also arguably laid the groundwork for the hip-hop revolution a decade later on the streets of New York City. As for Prince Buster, he wouldn’t get a hit until three years later, when British teens started adopting the Jamaican “rude boy” style—propelling the swaggering “Al Capone” to No. 18 on the British charts with it. [Katie Rife]

Professor Longhair, “Big Chief”

Professor Longhair’s piano style is essentially the textbook definition of “rollicking,” a wild, vamping take on the instrument that’d go on to define New Orleans jazz. Despite having some success throughout the ’50s, he was about ready to hang it up in 1964, when, on a whim, he recorded “Big Chief,” a song written by Earl King about his mother. Longhair’s impish, compulsively danceable piano figure is balanced by Smokey Johnson’s fleet-footed drumming, and that’s King himself whistling and singing the pidgin English lyrics. It’s an infectious track that flopped upon release, but a decade later, it and the rest of Longhair’s recordings were rediscovered and embraced. Today the song’s inseparable from Mardi Gras. [Clayton Purdom]

Paul Sindab, “I Was A Fool”

This era is littered with countless soul singers who’ve been forgotten by all but the most avid 45 collectors, many of whom only have one or two hidden gems to their name. But New York vocalist Paul Sindab’s short discography—nine songs released across a handful of labels—is almost nothing but gems, a collection of spirited soul cuts anchored by his electrifying voice and range. His most impressive performance of all might actually be on his first record: 1964’s “I Was A Fool.” Where other Sindab favorites, like the effervescent “Do Watcha Wanna Do,” leave his voice competing with crowded arrangements, the slinky, Latin-tinged groove of “I Was A Fool” gives him plenty of room to show off. And that’s exactly what he does, matching the song’s quiet cool during the verses but building to hair-raising high-pitched belts for the choruses, each one accentuated by a killer, sample-worthy drum fill. These days, Sindab reportedly lives a life far removed from show business—he’s said to be raising emus on a farm in Austin—but thanks to a pair of obsessive crate diggers who recognized his greatness, he made a one-time return to New York at the age of 72 to grace a new audience with his should’ve-been hits. [Matt Gerardi]

Raymond Scott, “Little Miss Echo”

The melodies of Raymond Scott are subliminal childhood shorthand, thanks to their ubiquity on cartoon soundtracks. And if the electronic lullabies of Scott’s Soothing Sounds For Baby series would’ve taken off, you’d have the big-band era’s most eccentric composer bouncing around in your head from birth. The undulating loops and infinitely sustained chords of “Little Miss Echo” would’ve sounded alien coming out of Johnson-era hi-fi sets; they’re essentially early, early, early experiments in ambience and minimalism, performed on instruments of Scott’s own design. But by the time the infants of 1964 had come of age, the context for such work would’ve grown up along with them. Ambient might officially begin with Music For Airports, but it was born with Soothing Sounds For Baby. [Erik Adams]

Bessie Banks, “Go Now” (January 1964)

The Moody Blues reached international stardom with their second-ever single, the blue-eyed-soul breakup ballad “Go Now.” But the song was written to be the breakthrough hit for a different artist, New York City soul singer Bessie Banks. Penned by her ex-husband, Larry Banks, a former member of the moderately successful doo-wop group The Four Fellows, an early demo of the song caught the ear of legendary hit-makers Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, who decided to pair Banks with veteran backup singers Dee Dee Warwick (sister of Dionne) and Cissy Houston (mother of Whitney), re-record the track, and release it on a subsidiary of their newly founded Daisy Records. Tragically, despite Banks’ full-throated, heartbreaking performance and all the stars being aligned to turn the song into another Leiber and Stoller smash, “Go Now” failed to make a splash on a national level. Worse, the Moody Blues released their cover version in less than a year’s time, overshadowing Banks’ superior original for decades to come. [Matt Gerardi]

The Rockin’ Ramrods, “She Lied” (April)

Following a pair of stomping, goofy surf-rock instrumentals released in 1963, the Rockin’ Ramrods cut “She Lied,” a thunderous protopunk kiss-off. The wall-of-sound guitars seem determined to pummel the listener into submission, with unfazed, pissy lyrics scorning an untruthful ex. It was enough of a hit in the group’s native Boston that it got picked up for a short stint opening for the Rolling Stones throughout New England. [Clayton Purdom]

Downliners Sect, “Be A Sect Maniac” (June)

Downliners Sect existed way out on the fringes of the same U.K. beat movement that birthed all the biggest British Invasion bands. What singer Don Craine and his crew lacked in imagination or even musical talent, they made up for with the frantic, infectious energy they poured into their shambolic reworkings of primordial rock ’n’ roll numbers and blues stompers. “Be A Sect Maniac” follows the latter approach, shamelessly repurposing the Bo Diddley beat into a goofy de facto theme song that has Craine croaking over jittering guitar and harmonica. This raucous approach to R&B won them success elsewhere in Europe, but the band’s individualistic streak led to a series of commercial flops—the freaked-out country tunes of Country Sect, the teenage-tragedy EP Sect Sing Sick Songs—and held it back from achieving the same kind of success that contemporaries like the Yardbirds and The Rolling Stones managed. But the Sect were punk before punk, and the same attitude that doomed them ultimately made maniacs out of tons of like-minded Brits who’d rise to stardom a decade later. [Matt Gerardi]

The Standells, “Help Yourself” (July 1964)

The Standells’ career fits nicely into two eras: before Ed Cobb and after Ed Cobb. In 1965, the band signed with Capitol’s Tower Records and were paired with Cobb, a songwriter and producer. They repackaged themselves into colorful mop-topped garage rockers and hit big with “Dirty Water,” a song written by Cobb after a trip to Boston and later immortalized as one of the city’s sports anthems. Prior to their “Dirty Water” moment, though, The Standells blended in with the legions of young suit-and-tie wearing Beatles-likes, playing clean-cut pop and blue-eyed R&B that was as indistinct as their look. The band’s second-ever single, a cover of bluesman Jimmy Reed’s “Help Yourself,” is one of the few gems buried in that rough patch. Reed’s original is as spare as electric blues gets, just his howling voice, a guitar, and a chugging snare. But led by a loose, swaggering performance from drummer and vocalist (and former Mousketeer) Dick Dodd, The Standells fleshed “Help Yourself” out into an energetic rocker full of handclaps, background shouts, and a hot-as-hell organ solo. It’s no “Dirty Water,” but it was the first real sign The Standells had a hit like that in them. [Matt Gerardi]

Wendy Rene, “After Laughter” (August 1964)

When Memphis native Mary Frierson signed to Stax Records as a teenager—first with quartet the Drapels, then solo—Otis Redding would be the one to christen her Wendy Rene. “After Laughter” was the first to be released under the moniker, and though it played well locally, it, like her subsequent dance-craze single “Bar B Q,” never took off nationally, and Frierson left the music business altogether in 1967 not long after fatefully backing out of the same Wisconsin trip that claimed Redding’s young life. Thirty years later, “After Laughter” was resurrected when Wu-Tang Clan sampled it for the 36 Chambers track “Tearz,” and it’s since been reworked by upwards of 50 different artists and counting. It’s easy to see why: There’s something otherworldly about this cut, something sublime in the combination of Booker T. Jones’ staccato organ progression, those wounded background harmonies, and Frierson’s devastating vocal performance. [Kelsey J. Waite]

Simon & Garfunkel, “Bleecker Street” (October)

Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel had already sort of hit it big in 1964, scoring a top 50 hit with “Hey Schoolgirl,” released in 1957 under Tom & Jerry. The childhood friends reunited years later for the sober folk collection Wednesday Morning, 3 A.M., half of which consisted of sober, somber folk covers. But the record’s first original composition, “Bleecker Street,” showed Simon already in full command of his songwriting powers, casting images of lonely poets and shadows in warm, delicate melodies. It was a later track on the record—“The Sounds Of Silence”—that a producer would convince the duo to re-record with full band accompaniment a few years later, launching them into stardom, but “Bleecker Street” required no greater adornment. [Clayton Purdom]

The Sonics, “The Witch” (November)

The Velvet Underground gets all the credit for launching the punk generation, but iconic American garage rockers The Sonics inspired more than their share of unbridled rock ’n’ roll as well. Frequently cited as a crucial influence on punk for the heaviness and aggressive simplicity of their music, like the Velvets, the Sonics were much more popular after the fact, and at the time of its release in November 1964, very few people outside of their native Washington heard the group’s debut single, “The Witch.” But acolytes have attempted to re-create its sloppy, frantic saxophone; driving, leaden drums; ragged vocals; and overdriven guitar in garages around the globe ever since. [Katie Rife]

Them, “Baby, Please Don’t Go” (November)

Them may be known best as the launch pad for Van Morrison, who formed the group in the early 1960s in Belfast. The Northern Irish group released relatively few hits, but its influence shaped both Van Morrison’s solo career and The Doors, who opened for Them during part of Them’s U.S. tour in 1966. “Please Baby Don’t Go” is one of many blues-rock covers of a Big Joe Williams song from 1935, and Them’s version borrows the core of Williams’ American-blues grit and builds on it with hard-driving garage rock sound and layers of piercing guitar lines and keyboards. (The studio version also features then-session-musician Jimmy Page.) The song reached the Top 10 in the U.K., but despite being marketed to U.S. audiences as part of the British Invasion, never cracked the American charts. The A-side of “Please Baby Don’t Go,” however, was “Gloria,” which twice hit the Billboard Top 100 chart. [Laura M. Browning]

RECOMMENDED FURTHER LISTENING

The Trey Tones, “Nonymous”

Karlheinz Stockhausen, “Kontakte”

John Fahey, “Poor Boy A Long Way From Home”

The Plebs, “Babe I’m Gonna Leave You”