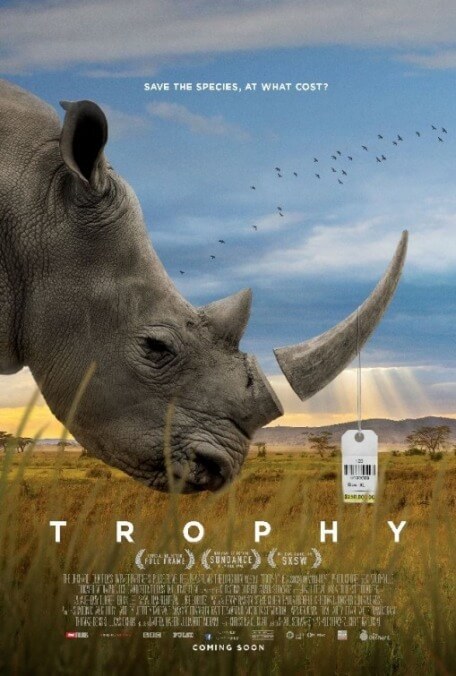

Which sounds more painful to watch, for those sensitive to animal suffering: a deer being shot for sport, or a rhinoceros being forcibly held down and having its horn sawed off? Trophy, a documentary about the uneasy, seemingly oxymoronic junction of big-game hunting and conservation efforts, kicks off by showing both of these events, and speedily reveals that neither situation is as clear-cut as it might initially seem. The group of folks who mutilate the rhino do so in an effort to save its life—the amputation is painless (no different, really, than clipping one’s fingernail; both are made of keratin), and the animal, until its horn grows back, is theoretically of no value to the poachers who would otherwise kill it. Such measures are financed, in large part, by hunters like Philip Glass (not the minimalist composer), who pay enormous sums in order to travel to Africa and bag “the big five”: elephant, lion, leopard, cape buffalo, and rhino. Is it acceptable to let rich people kill a few animals for “fun” if their cash might potentially save many others?

Trophy ostensibly maintains a neutral point of view, allowing people on both sides of various issues to make their best case. Some of their arguments will fall on deaf ears. John Hume, the man leading the team that de-horns rhinos, argues strenuously throughout the film that bans on the sale of ivory should be lifted, because they ultimately hurt rhinos more than they help them; he spends a lot of time being yelled at by angry protestors. Glass, meanwhile, justifies his love of hunting by quoting scripture (specifically a passage in Genesis about God giving human beings dominion over the animals) and brags that no bureaucrat can take his pleasure in a kill away from him. (He also insists that only a fool would believe in evolution, just to burn one last bridge with a certain cross-section of viewers.) Various other interview subjects come and go, without any individual ever really attaining a position of authority. This approach is at once admirable and frustrating, acknowledging complexity to a degree that amounts to a big shrug.

Indeed, Trophy’s tendency to wander is its greatest liability. There’s some digressive outrage directed at what are called “canned hunts,” in which the animal to be shot has essentially been pre-captured and remains confined in a small area, with no real chance of escape. There are legitimate reasons to decry this practice (though the notion that it’s “not sporting” seems a tad silly—the human having a rifle that can kill at a great distance isn’t exactly sporting either), but the issue is tangential at best to Trophy’s larger concerns, and feels like a cul-de-sac from which the film emerges with great clumsiness. It’s also slightly unfortunate—though admittedly no fault of director Shaul Schwarz (assisted by Christina Clusiau)—that Trophy covers a lot of the same ground as did recent Netflix documentary The Ivory Game. This film is more rhinocentric, with elephants and their tusks addressed fleetingly by comparison, but the battle against poachers and the free market is similar enough to make one doc fairly redundant if you’ve seen the other. What’s abundantly clear is that every other species on Earth is at our mercy, and that there are no easy answers when it comes to determining the most compassionate form of our so-called dominion.

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)