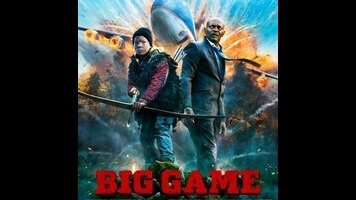

If nothing else, Finnish writer-director Jalmari Helander has a knack for cooking up premises so absurd that they can’t help but intrigue. His debut feature, Rare Exports: A Christmas Tale, posited Santa Claus as a Cthulhu-like figure served by feral elves. His follow-up, reportedly the most expensive Finnish film ever made, finds the president of The United States (Samuel L. Jackson) getting shot down over Lapland by an oil heir who intends to hunt him for sport, with his only chance at survival coming in the form of a local boy who has gone into the wild as part of a family rite of passage. But aside from a handful of appropriately ludicrous vistas—a rocky field strewn with the bodies of Secret Service agents whose parachutes failed to deploy; Air Force One resting half-submerged in a mountain lake—Big Game fails to live up to the kookiness of this set-up. Instead, it opts for ’90s action movie clichés and generic coming-of-age-isms. Helander’s inelegant, exposition-heavy English-language dialogue doesn’t help matters.

On the day before his 13th birthday, Oskari (Rare Exports’ Onni Tommila) is given an ATV loaded with supplies and a hunting bow, and sent off to bag an animal that will prove his manhood. Meanwhile, in the skies above, lame duck President William Moore is en route to a pre-G8 summit in Helsinki. Air Force One takes a hit from a surface-to-air missile, its security sabotaged by veteran Secret Service agent Morris (Ray Stevenson). Moore is loaded into an escape pod (entry code: 1492) while Morris escapes in a parachute as the plane descends in flames into the Finnish wilderness. In case there was any doubt about Helander’s frame of reference, it should be pointed out that the escape pod and the parachute ramp, both fictional, figure in Air Force One and that Moore ends up on the ground short of footwear, like Die Hard’s John McClane. (Jackson, of course, co-starred in Die Hard With A Vengeance, though reportedly Helander’s original choice for the role was Mel Gibson, a reference that comes loaded with its own subtext.)

Big Game’s fixation on recreating the feel of a ’90s American blockbuster verges on the academic. The action sequences ape the clearer visual grammar of the Clinton era, complete with those cuts from wide shot into long-lens medium that used to accompany an explosion. Moments of bad comedy—like an extended early sequence where Oskari mistakes the escape pod for a UFO, and its occupant for an alien—feel like studied imitations of Hollywood corniness, as does the bond that develops between Moore and Oskari. (Jackson and Tommila, however, effectively underplay their roles, though the same can’t be said for the rest of the cast.) Helander is clearly interested in playing around with the mythology of popular culture, and here he picks two macho, self-mythologizing traditions—the American action movie and Finnish hunting—and places them side by side. What he doesn’t do is subvert them, or get them to interact in any meaningful way. Recognizing and recreating clichés is one thing, but when you don’t do anything novel with them, they remain just that—clichés.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.