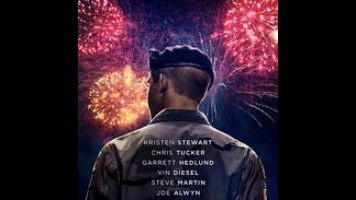

Not every Ang Lee movie explores a facet of American history, but periodically he reaches into this nation’s past and delivers a fresh perspective on, say, ’70s suburban ennui or ’60s idealism. Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk takes place in an era that for many will barely qualify as historical, signified by cruder cellphones and an active Iraq War. In the fall of 2004, after “Mission Accomplished” but well before withdrawal of troops, Billy Lynn (Joe Alwyn) returns home. He’s not there for good, but to appear with his fellow Army squad members in a Thanksgiving Day halftime show. They’ve all been hailed as heroes in the media following a particularly harrowing battle that happened to be caught on camera.

The movie, adapted from a novel by Ben Fountain, follows Billy during this trip stateside, with a few flashbacks whisking him and the audience back to the time of that fateful armed conflict. Billy has ambiguous feelings about his heroism and what the war has done to him, while his sister, Kathryn (Kristen Stewart), less ambiguously implores him to seek treatment for PTSD, which could excuse him from returning to active duty. Loyalty to his fellow soldiers, including the gruff Sgt. Dime (Garrett Hedlund), keeps Billy from embracing this option.

The soldiers are also pursuing a possible movie deal (the details of which seem vaguely tone-deaf to the process of movie deal-making), which puts them into contact with manager figure Albert (Chris Tucker) and potential bankroller Norm Oglesby (Steve Martin). Lee isn’t quite going to Informant! levels of using comedians in non-comic roles, but Tucker and Martin certainly contribute to the eclecticism of a cast that also includes Vin Diesel as one of Billy’s brothers in arms (with the very Diesel-y guttural-noise name of Shroom). But the story of Billy Lynn doesn’t match the appealingly odd ensemble. It has the dinner-table conflicts, raw soldiers’ nerves, and implied lamentations about the gaps between media-approved heroism and the realities of the battlefield of other modern war movies. Sometimes it recalls nothing loftier than the half-forgotten (but good) Kimberly Peirce film Stop-Loss.

It’s not the storytelling that’s supposed to up Billy Lynn’s game, though. To shoot his relatively intimate 2004-set drama, Lee has used cutting-edge technology: digital video that captures images at 120 frames per second of 4K resolution, in 3-D to boot. It’s a leap forward from the oft-derided techniques Peter Jackson used to make his Hobbit trilogy—so far forward, in fact, that no one is really sure if they want to leap along with him. The movie will only be projected at 120fps at all of two theaters in the United States (some theaters will show it at 60fps, while Lee has also prepared a traditional 24fps version).

Lee used 3-D as well as it’s ever been used in Life Of Pi, so he deserves the leeway to tinker with whatever tech he wants to try out, and the 120fps version of Billy Lynn is something to see (technically, anyway; practically, it’s not especially available to be seen in its native form). The format has been touted by some filmmakers as particularly immersive and vividly realistic, and while the clarity and brightness of the 3-D image is astonishingly window-like at times, this description isn’t entirely accurate. Movies that look like ultra-HD live broadcasts don’t actually look more like real life, because the images are still shown on a screen out of scale with the viewer’s actual physical settings, with all the neat stuff (cuts, camera movements, etc.) unavailable in real life. Illusion is a built-in part of movies, even those aiming for realism, and in attempting to diminish one kind of distance (Lee wisely has his actors go makeup-free, or at least makeup-light, because their faces can be seen so clearly in this format), the movie just creates another, arguably weirder distance.

As it turns out, that odd concoction of intensity and distance works well for certain sections of Billy Lynn. During the actual halftime show, as Lee’s camera pushes behind the scenes in a wide tracking shot, the 120fps version’s resemblance to a live broadcast makes a lot of sense, blowing the spectacle up into a kind of supersized, borderline surreal discomfort, complemented by details like clueless civilians attempting to use military lingo. When exploding fireworks throw Billy’s mind back to the combat scene in Iraq, the battle looks both real in its terrifying urgency and broadcast-ready in its live-feed video texture. It’s both realistic and removed. Whether this is Lee’s intended effect or not, it works in a way quite unlike any other movie.

But before these two nested showpieces, where PTSD, confusion, hostility, and yearning all simmer under Billy’s skin, much of the movie feels familiar. The 120fps cinematography, with its tendency to make camera movements look less natural and more noticeable, sometimes ushers that familiarity over the line into staginess. This is an uncharacteristically unsubtle work from Lee—yet in the end, it’s not ineffective. The almost invasive close-ups allow newcomer Alwyn to go small, even when Billy Lynn swings a little broad, and he holds the movie together when the more famous supporting cast doesn’t get enough to do. The movie’s heartbreak lingers, as Lee makes a convincing case that the wounds of over a decade ago, whether they feel immediate or distanced, may not heal so easily.

![Rob Reiner's son booked for murder amid homicide investigation [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/15131025/MixCollage-15-Dec-2025-01-10-PM-9121.jpg)