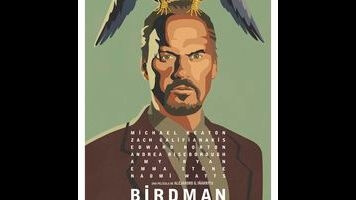

Birdman puts Michael Keaton back under the shadow (and cowl) of a superhero

For Michael Keaton, Birdman is some kind of gift from the movie gods, a license to have his cake and messily devour it too. It’s the casting coup of the year: aging former movie star who once played a winged superhero returns as an aging former movie star who once played a winged superhero. The role, custom-fitted to Keaton’s true Hollywood story, allows him to toy with his own faded celebrity and to step back (however briefly) into the vulcanized rubber of a crime-fighting getup. Invisible quotation marks flutter like bats around the actor’s head, fortifying his performance with context and subtext. Cursed/blessed with terrible facial hair, and always walking or yelling or arguing with himself, Keaton hasn’t seemed this alive in years. Maybe ever.

Same goes for Alejandro González Iñárritu, unlikeliest of directors to tackle a playful, self-consciously meta, showbiz comedy. Under his stewardship, Birdman is less a movie than a kind of grand magic trick, designed to dazzle and delight and make the audience feel exceptionally clever, but not to hold up to too much scrutiny. Beyond the incredible stunt casting, there’s a shamelessly impressive formal gimmick: Most of the film has been shot to resemble a single, unbroken take, the great Emmanuel Lubezki (Gravity, Children Of Men) masking cuts under cover of backstage darkness. This creates a sense of perpetual urgency, and for all the potshots it takes at Hollywood’s superhero obsession, Birdman has the crowd-pleasing instincts of a studio blockbuster.

Keaton’s “character,” Riggan Thomson, is mounting a Broadway show, a Raymond Carver adaptation he’s written, directed, and will star in—mostly, as everyone speculates, to prove that he’s not a talentless has-been. The film takes place over a few weeks, in and around New York’s famous St. James Theatre, as Riggan attempts to assuage the worries of a harried assistant (Zach Galifianakis), make nice with his resentful daughter (Emma Stone), and not completely embarrass himself on stage. Instead of jumping around in time, as he did with 21 Grams and Babel, Iñárritu condenses it, his ersatz long-take making a fortnight feel like one endless opening night. It’s not the only bend in reality: When not putting out fires, Riggan carries on contentious conversations with his masked alter ego; usually invisible, the taunting companion sounds more like Christian Bale’s gravel-voiced Dark Knight than Keaton’s whispery caped crusader.

Much of the cast seems to have been hired at least partially for the echoes their involvement creates. Naomi Watts, for example, plays a radiant, aspiring star; the Mulholland Drive connection is plain even before she locks lips with a raven-haired costar (Andrea Riseborough)—and imagining what David Lynch could have done with the material does no favors to Birdman. But beyond the intentional baggage brought aboard, nearly everyone on-screen is spectacular, none more so than Edward Norton. Cast as a famously difficult Method performer, the famously difficult Method performer channels all of his asshole reputation into this demanding, egotistical figure, the worst of Riggan’s many problems. He’s an extraordinary prick, but also unknowable: Norton’s scenes with Stone on the balcony of the theater reveal new dimensions to the character, as though he were reborn in her presence.

Speaking of rebirth, Iñárritu relocates an energy and passion—a sheer verve—that’s been missing from his work since Amores Perros. Perpetually gliding through the labyrinthine innards of the theater, often to a Punch-Drunk Love beat of percussive anxiety, he captures the hustle and bustle of the backstage world—the electricity in the air when a live performance is imminent. There are a few shades of Babelish self-importance: The scene where Riggan cuts down the spiteful, disingenuous methodology of an icy theater critic (Lindsay Duncan, the film’s very own Anton Ego) swells with righteous defensiveness. But couldn’t the man’s critique, predicated on her use of references as a crutch, be applied to the movie itself, which name-drops everyone from Roland Barthes to Justin Bieber? That’s the type of hypocrisy that Birdman seems to intentionally indulge, deflecting criticism by embracing its contradictions.

But is Riggan’s play any good? Does the actor have hidden reservoirs of talent, or is he the hack his detractors assume him to be? The film never deigns to decide on such matters, probably because it’s more interested in process than product: What’s going on in the artist’s mind, and bleeding its way into his real world, is more important to Iñárritu and his three cowriters. As for the war between stage and screen, Birdman calls something of a draw. The epic steadicam take(s) mimic the way theater operates, with the actors becoming immersed to a degree unobtainable through a standard shot/reverse-shot filming strategy. At the same time, Iñárritu and Lubezki create moments—like a late, literal flight of fancy—that only cinema can accomplish. For all the winks and nods and inside-baseball irony, Birdman gets airborne only when it’s celebrating, instead of skewering, its hero’s twin vocations. In those moments, the film is a gift to its audience, too.