Birds Of Passage traffics in cliché, wrapping a familiar crime yarn in fascinating cultural fabric

The first thing we see in Birds Of Passage, a drama set among the Wayúu people of northern Colombia, is a ritual courtship dance that seems to accompany a young woman’s coming-of-age ceremony. Entering a circle of family and friends, the man seeking the woman’s favor proceeds to run backwards, while she, face painted and wearing a cape-like fabric, charges toward him with the cape’s “wings” stretched out wide. It’s a memorable sight, suggesting that the film will explore a culture unfamiliar to most American viewers. Instead, however, Birds Of Passage quickly veers onto a well-trod path, becoming just the latest portrait of a bloody war among drug dealers and distributors. Unique background elements provide flavor, but apart from the drug of choice here being marijuana rather than cocaine, what unfolds could hardly be less rote.

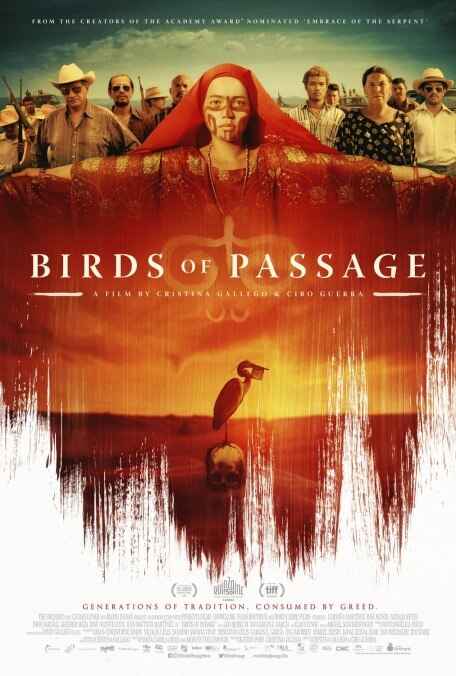

Directed by Cristina Gallego and Ciro Guerra, who previously collaborated on the Oscar-nominated Embrace Of The Serpent (though only Guerra was credited as director on that one, with Gallego as producer), the movie has been divided into five “cantos,” or songs, spanning 1968 to 1980. After dancing with Zaida (Natalia Reyes) in the opening sequence, Rapayet (José Acosta) is told that he’ll need to come up with a hefty dowry: 30 goats and 20 cows, plus some expensive jewelry. Desperate, he forges an alliance with a neighboring, apparently different-yet-related group, trading coffee for weed and then selling the latter to some Peace Corps hippies. This arrangement quickly blossoms into the same illicit business model recently seen in such films as American Made and Loving Pablo, with gringos flying the drugs out in small planes and leaving giant bundles of cash in return. Rapayet and Zaida wed and start a family, which of course only means that there are more ready victims on hand when things inevitably turn violent.

Gallego and Guerra clearly want to show how the advent of the drug trade destroyed previously peaceful indigenous communities, and they make a point of noting longstanding customs—like a taboo against harming a “word messenger”—that get tossed aside in the name of greed and revenge. The more Wayúu-specific Birds Of Passage is, the more compelling. Its broad strokes, however, frequently amount to Embrace Of The Cliché. “I knew you didn’t have it in you,” sneers a man being held at gunpoint by his best friend, following a brief interlude of trigger-free tension. Anyone care to guess what occurs half a second later? Plus, all of the tragedy that befalls these characters over more than a decade is generated by not one but two impulsive idiots in the time-honored mold of De Niro’s Johnny Boy (with Rapayet as the pragmatic Charlie). The film needs this figure so badly—to gun down business partners for no good reason, or to rape the weed supplier’s beloved daughter and kick off a cascade of vengeance—that it starts grooming a replacement even before the first one gets killed! That sort of generic macho posturing, borrowed from dozens of previous action movies, turns fascinating cultural elements into mere window dressing for a standard-issue trafficking body count.