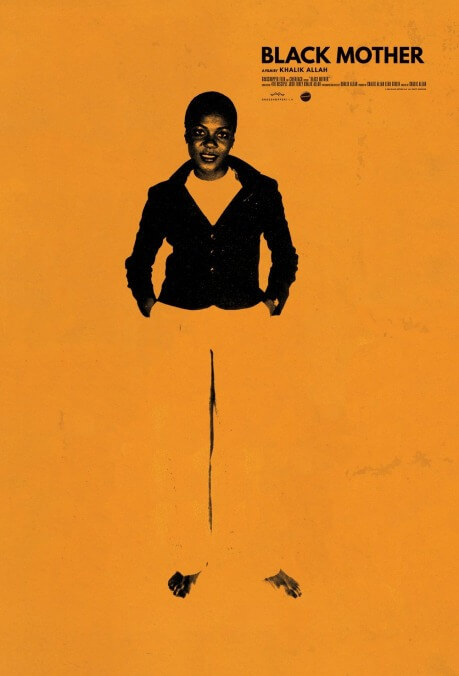

Black Mother is a personal, radical, expansive portrait of Jamaica and its people

Black Mother, Khalik Allah’s latest documentary feature, may be considered something of a homecoming project for its photographer-turned-director. Filmed in Jamaica over a period of two years (during which time he also contributed to Beyoncé’s Lemonade, specifically the New Orleans portions), the film is a return to his maternal ancestry. From the opening scene, though, which goes from a rendition of “Jamaica Home” to ultrasound footage of a pregnancy to audio of a man soliciting a sex worker, it’s clear that this isn’t going to be a staid autobiographical portrait. Indeed, though the film incorporates personal VHS home video footage as one of its many presentation formats—which also include Super 8, 16mm, and HD video—the presence of the director’s family is minimal, bordering on incidental. Rather, the film is an expansive snapshot of the Caribbean island nation.

Divided into three sections, each named for a trimester of pregnancy—thereby conflating black womanhood and Mother Earth—Black Mother doesn’t shy away from hefty subjects: the travails of sex work, the remnants of colonialism, and the enduring dominance of religion, to name but a few. But what distinguishes the film is Allah’s superb eye and talent for portraiture, first showcased in his 2015 documentary Field Niggas, which explored U.S. racial tensions and police brutality through a series of slow-motion portraits taken on the corner of 125th Street and Lexington Avenue in Harlem. (One might productively consider his images alongside the head-on closeups in Barry Jenkins’ recent If Beale Street Could Talk.) Here, the director trains his camera on preachers and sex workers, street vendors and devout young women—all emblematic of his chosen topics, but presented with an autonomy that refuses easy condescension, judgment, or pity. As in his previous feature, Black Mother is almost exclusively composed of unsynced sound, so we might be hearing an anecdote of a man’s hand being cut off at one moment, a chorus of children singing “Jesus Loves Me” in the next. The effect is disjunctive and occasionally confounding—but intentionally so, as Allah’s methodology seems to prize what a viewer might initially take as error. It’s no accident that much of the film footage he includes is imperfectly scanned, such that any given frame often contains an intrusive sliver of the next.

As the images flicker before our eyes in a barrage of changing aspect ratios and formats—with visual artifacts, flares, and blemishes all retained—Allah’s tactile presentation reminds us, if nothing else, of what it means to be there, in the moment, filming a person just a few feet in front of you. His quicksilver editing patterns force us to recontextualize what we see, which is in keeping with a documentary that traffics in myriad juxtapositions and dichotomies. Equally adept at evoking religious spiritual fervor and a hustler’s urgency, Allah doesn’t play down such contradictions but rather delights in them, locating ample beauty in the nation’s bucolic natural landscapes, its places of worship (which number the highest per area of any country in the world), and its teeming, grimy streets.

There isn’t much in the way of a through-line across these 77 minutes. (Even RaMell Ross’ Hale County, This Morning, This Evening, for all of its free-floating, nonlinear poetry, still anchored its movements to the lives of two black men.) And though we do get snippets of history here and there—the origins of Rastafarianism, an account of National Hero Sam Sharpe, the Baptist minister who led the 1832 Christmas Rebellion—Black Mother can’t rightly be considered a collection of vignettes, either. As Allah’s images cascade before our eyes, we mostly come to recognize recurring faces and bold visual motifs (water, most prominently), and get an uncanny, discombobulating sense of moving through various spaces. (During the final passage, a brief coda dubbed “birth,” a hypnotic top-down shot of waves breaking on the shore, is a highlight.) Black Mother can at times feel nebulous, but the richness of lived experience that it captures, augmented by Allah’s transportive gestures, are more than enough to compensate.