The film opens in Amsterdam, where ‘Ndrangheta lieutenant Luigi (Marco Leonardi) is brokering a drug deal with some South American compatriots. During the meeting one compliments him on his Spanish, which suggests that when it comes to business, Luigi is an internationalist—he likes moving in foreign circles. His older brother Luciano (Fabrizio Ferracane) is more locally minded: While Luigi and middle sibling Rocco (Peppino Mazzotta) have embraced their heritage as criminals, he’s stayed behind in the south to work the land and tend to a flock of goats. It’s a simple existence that doesn’t seem to make him happy so much as keep his more volatile tendencies under wraps.

The tension between these two family businesses, both steeped in tradition, will be felt throughout Black Souls, most acutely in the character of Luciano’s teenaged son Leo (Giuseppe Fumo), who is drawn to the excitement and material satisfactions of his uncles’ lifestyles, and wants to join their ranks as soon as possible. Leo’s attempt to show off his bad-boy bona fides results in an impromptu family reunion in the tiny mountain town of Africo Vecchio, which is depicted by Munzi with a dreary lyricism: The physical beauty of the landscape belies the paralyzing boredom of idyllic village routines. It’s dull, but it’s also dangerous. The sunshine and salty ocean air seem to preserve tribal grievances long past their practical expiry date.

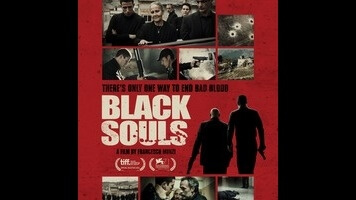

Black Souls has been conceived as a tragedy rather than a thriller, and the tone is appropriately melancholic. Munzi has cast the film wisely (the three leads all seem to have dropped from the same subtly rotten family tree) and he’s skilled at using widescreen compositions to suggest the feelings of the people on-screen, clustering lustrous bodies and faces within the frame so that we can perceive the intimacy between them (or a lack thereof). This is a very well-made movie, and yet aspects of it also feel secondhand; Leo’s impetuousness too strongly evokes Sonny Corleone and The Sopranos’ Jackie Jr., while the juxtaposition of organized crime and quotidian, everyday reality feels similarly derivative. (One film that comes to mind is Ben Wheatley’s far more baroque Down Terrace, which also takes the form of a family tragedy, albeit tilted towards farce.) Black Souls is chilling, but it’s also familiar. The characters might not see what’s coming, but the audience can spot it a mile away.

![Rob Reiner's son booked for murder amid homicide investigation [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/15131025/MixCollage-15-Dec-2025-01-10-PM-9121.jpg)