Blade paved the way for the Marvel blockbusters of the new millennium

Stan Lee always wanted to make movies. In the ’60s and ’70s, the comic book writer helped to create dozens of characters, and he also laid the groundwork for hundreds more to come into existence. He’d always had the idea that these characters belonged in movies. By 1981, he’d moved away from Marvel’s New York offices to Los Angeles, where he hoped to get some of these movie ideas off the ground. It didn’t work out.

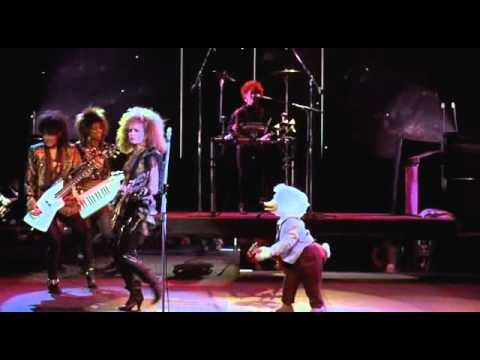

By 1998, the only Marvel movie to get any kind of proper release had been Howard The Duck, the legendary 1986 flop in which the titular anthropomorphic duck fights a giant stop-motion alien monster, fends off the advances of a horny Lea Thompson, and plays a guitar solo. It is a movie intended for children, full of duck-related puns, that nevertheless features multiple shots of naked duck-lady boobs. This was a big-budget cinematic failure of grand and dizzying proportions, and it did not exactly have studios lining up to turn Marvel characters into the stars of major motion pictures.

A few other Marvel movies did get made. The Punisher became a not-bad 1989 vehicle for Dolph Lundgren, the type of movie where the hero ends up fighting mobsters and ninjas. Captain America and The Fantastic Four both got hokey and ultra-cheap adaptations, movies that are near-unwatchable by today’s standards. The Punisher and Captain America both went straight to video in the U.S. The Fantastic Four never even came out. While this was happening, Marvel’s competitors at DC had launched two global-blockbuster movie franchises for Batman and Superman. Even the underground comic The Crow became a successful movie before Marvel got its shit together.

As a ’90s kid who read comic books, I found this to be a perpetual source of irritation. I didn’t care about DC, and I did care, deeply, about Marvel. And yet the only time the people at Marvel had any success adapting their characters for the screen was in the pretty good early-’90s X-Men Saturday-morning cartoon. There were reasons for this. Marvel was tied up in corporate hell, going bankrupt and passing from one owner to the next. The company sold off rights of characters to companies that just weren’t equipped to do anything with them, especially given the capabilities of the era’s special effects. Sometimes, Marvel would sell rights to a company that would promptly go out of business itself, thus throwing those rights into legal limbo. The interest was there; James Cameron once tried valiantly to get a Spider-Man movie made. But nobody managed to get anything done. Until Blade.

Blade was never a major character for Marvel, even after he became the star of a successful franchise. Marv Wolfman and Gene Colan had created the character in the early ’70s, making him just one member of a team of vampire hunters in their series The Tomb Of Dracula. Blade wouldn’t get his own series until 20 years after his debut, and he wouldn’t become a half-vampire daywalker in the comics until 1999, after he’d already been one in the movies. Reading comics, I’m pretty sure I’d only encountered Blade as an occasional teammate of Ghost Rider in the Midnight Sons imprint. As a character, he had no name recognition. He was a C-lister.

And yet New Line, after making a bunch of money with Friday, had seen commercial potential in a story about a black hero, and the screenwriter David S. Goyer, who’d gotten his start writing stuff like Death Warrant and Demonic Toys, and who would later become the architect of DC’s cinematic universe, had some ideas for the character. It’s a miracle that a Blade movie ever got made in the first place, and it’s even more of a miracle that it ended up being any good. But it was extremely fucking good.

In my previous A.V. Club column, A History Of Violence, I wrote about Blade as an action movie. Within that genre, it’s an absolute classic, a fast and cheap American studio B-movie that integrated the tricks and physicality of Hong Kong martial arts movies and helped prepare the world for The Matrix. In the superhero realm, though, it might be even more important. Blade established a foothold for Marvel, which turned out to be huge. But after the slack-jawed silliness of the Joel Schumacher Batman movies, it also showed a different way to present superheroes on screen, one that was theatrical and over-the-top but still hard and physical and grounded. And Blade also did some things better than any superhero movie, before or since, has ever done.

With Blade, Goyer and Stephen Norrington, the British director whose only previous credit was the horror flick Death Machine, constructed a world with a dazzling efficiency. Blade shows us a whole hidden society: a vampire world with its own politics and prejudices and grudges, operating in plain sight, with the cooperation of human authorities. That vampire society is divided. There’s the old guard, which wants to keep its delicate balance with the human world intact. The younger vampires, meanwhile, just want to lure unsuspecting doofuses into underground raves where blood pours from the ceiling. And then there’s Blade, the obsessed half-vampire bogeyman who has turned vampire eradication into his reason for being.

The movie reveals its world piece by piece. Blade doesn’t devote its entire first act to its hero’s origin story. Instead, we’re halfway into the movie before we even learn how Blade has his powers, and we only get that story in a quick monologue from Whistler, Blade’s grizzled sidekick. When Blade first shows up—appearing suddenly at a blood-rave without a drop of hemoglobin on him, the entire room cowering at the sight of him—we know all about him that we need to know. And so the movie throws us headlong into action, giving us a truly great fight scene before Blade so much as says a single word. (If only more superhero movies had that sense of momentum.)

Blade isn’t a superhero, at least in the way it’s traditionally understood. He doesn’t have an alter-ego. He doesn’t wear a mask or a cape or a costume, though maybe there’s something ostentatious in the way he lets his leather duster billow out behind him. He offers very little in the way of the witty repartee that’s become so prevalent in superhero movies today. He’s driven by revenge, not any sense of duty. He’s into killing, whether it’s vampires or the human familiars who work for vampires. He’s a larger-than-life character, and he’s gloriously absurd in that late-’90s movie way, with his tribal tattoos and his leather pants and his ever-present Oakleys. But the movie treats him with total seriousness, and it would fall apart if it didn’t.

In Wesley Snipes, Blade had a star who was willing to fully invest himself in the movie’s goofy vision. Snipes talks as little as possible, radiating laconic contempt and impatience like Clint Eastwood circa Dirty Harry. He smiles to taunt the vampires he’s about to kill. He moves with economical ferocity, and the movie is smart enough to take full advantage of his martial arts skills. He also has the weathered, growly Kris Kristofferson as Whistler, the anti-Alfred and the best sidekick in superhero-movie history. (Goyer created Whistler for the movie, but he later showed up in the comics, a rare screen-to-page transition.) Snipes and Kristofferson had both accomplished great things in their careers. Snipes had played Nino Brown! Kristofferson had written “Sunday Morning Coming Down”! On some level, they must’ve been chasing paychecks in Blade. But they never gave that impression. Instead, they come off as actors with complete ideas about who their characters are.

As the villain Deacon Frost, the young vampire iconoclast who wants to resurrect an ancient blood god, Stephen Dorff doesn’t have the same level of commitment as Snipes or Kristofferson, and he dates the movie every time his spiky-rumpled-bangs haircut shows up on screen. But he’s a blast to watch anyway, and his motives make sense, something that remains all too rare in superhero-movie heavies. Frost had been a comic book character, a sort of mad vampire scientist who can clone himself. But the movie remakes him completely. Here, he’s a pariah within the stuffy elder-vampire society, a flashy kid whose blood-rave parties threaten to draw too much attention. They discriminate against him because he was bitten rather than born a vampire. He hates them because they want to maintain peace with humanity rather than freely preying on whomever, whenever. He’s got a bloodthirsty late-’90s model-waif girlfriend and Donal Logue as a flamboyant henchman. And he’s got enough swagger that you almost want to root for him.

Blade was a movie without a huge budget, and some of its early-CGI effects haven’t held up all that well, though they’re leagues beyond, for instance, the pixelated puke of 1997’s Spawn. (Credit Norrington with reworking Blade’s finale when he realized that its digital blood god looked terrible.) Nobody expected it to be good; I went to see it opening weekend figuring that it might be pretty funny. Within minutes, I knew I was watching something special. Blade went on to make money and to spawn two sequels (including one absolute classic, Guillermo del Toro’s Blade II). And while it didn’t revolutionize superhero movies, it paved the way for movies that did.

The superhero-movie era didn’t begin in earnest until two years later, with X-Men. That was a summer blockbuster, not a mid-budget surprise success, and yet X-Men learned some things from Blade. Its heroes and villains were all people with goals and ideas that made sense within context. They all lived in an alternate world with its own easily explained rules and customs. Hugh Jackman played Wolverine as a gravelly, grim, sometimes-funny take-no-shit warrior, a character not dissimilar from Blade. And finally, the movie studios figured out how to turns comic book characters into effective movie avatars. Motherfuckers stopped trying to ice-skate uphill.

Other notable 1998 superhero movies: There’s really only one other superhero movie from that year, and weirdly, it’s another Marvel adaptation written by David S. Goyer. That would be the made-for-TV movie Nick Fury: Agent Of SHIELD, in which the role of Marvel’s seen-it-all global super-spy goes to, of all possible people, David Hasselhoff, who’d already made cheese-TV history with Knight Rider and Baywatch but who had not yet become a professional self-mocker. Hasselhoff actually works hard to invest his Fury with some hard-bitten authority, and Goyer’s script sticks as closely as possible to the SHIELD/Hydra battles of the comics. But it’s a cheap, charmless Fox production. Every set is some metal control panel with ladders and hatches and sparks flying, and the grim, artless gunfights and bleeping-digital-clock countdowns all go exactly the way you might think. This was clearly meant as the pilot to a TV show, and it’s probably good that the show never got picked up. Ten years later, Samuel L. Jackson would appear on screen as Fury for the first time. And 19 years later, Hasselhoff would get a quick cameo in Guardians Of The Galaxy Vol. 2.

Next time: An all-star comedy cast brings the lesser-known superhero-spoof comic Mystery Men to life.