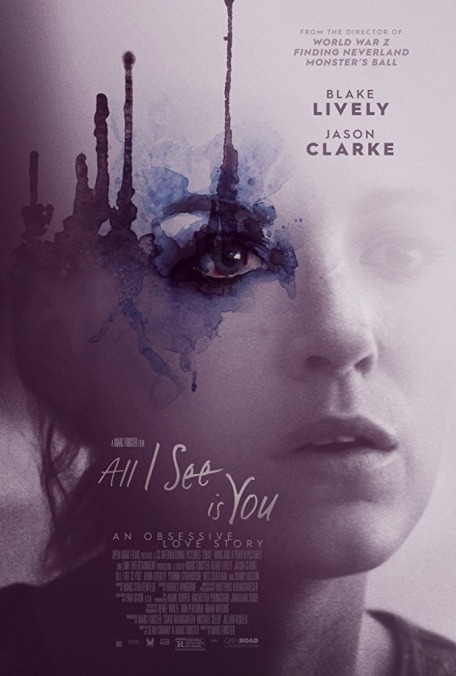

Blake Lively tries to bring clarity to the overly stylized All I See Is You

Did Green Lantern permanently cure Blake Lively of any interest in paycheck blockbusters? For someone who got famous on a CW teen soap, Lively has shown an eagerness to make movies for adults, taking supporting roles in films like Café Society, The Town, and Savages; even her recent summer movie feels more elemental and old-fashioned than most. Lively’s concise work as a big-screen lead has been arguably even more idiosyncratic, if not entirely successful. After the eternal-youth drama The Age Of Adaline, Lively now stars in All I See Is You, a nebulously classifiable sort-of thriller-drama from director-cowriter Marc Forster.

She plays Gina, a woman who was blinded during a childhood accident, and now lives in Bangkok with her husband James (Jason Clarke). Gina has grown accustomed to a sightless life, but she and James are still excited to hear about a surgical procedure that could restore vision in her right eye. With James pressing the doctor on what they might do if the operation fails, a more subdued Gina gives it a try. Sure enough, she starts to see better; point-of-view shots show her vision gradually emerging as if from a slowly clearing mist.

Misty POV shots are some of the less ostentatious tricks up Forster’s sleeve. More or less from the jump, when the movie depicts sex scenes through a kaleidoscopic barrage of tiny images, flashbacks through seconds-long cutaways, and details through impressionistic close-ups, the style of All I See Is You speaks in sensory overload, not unlike a Danny Boyle movie. It’s also not unlike one of Forster’s least-seen previous films: the 2005 oddity Stay, an outlier in a filmography that includes several adaptations of bestsellers, multiple additional movies about writers, and an efficient if little-loved James Bond installment.

Stay hung its entire story on a ludicrous dead end of a twist; All I See Is You burns itself out more deliberately, and less fantastically. The movie takes its time—not an unwelcome quality as Gina adjusts to her newly restored sense. Its story, and Lively’s performance along with it, hinges on the question of whether this kind of change can in turn cause a shift in personality, priorities, and desires. Clarke’s performance, meanwhile, hinges on the question of whether James will react to these potential changes with testiness or full-blown irritation.

As discomfortingly familiar as it is to see an older, less charismatic male performer paired with a younger, more vibrant one, All I See Is You does address this gap through the insecurities James feels as his wife explores the newly expanded boundaries of her world. Unfortunately, it does this by prodding Clarke into a grumpiness that acts as a limiter for the movie’s ambitions. The other characters, like Gina’s sister Carla (Ahna O’Reilly) and her button-pushing husband Ramon (Miquel Fernández), become plot points on a confused map of sexual dysfunction. The movie has a lot of sex, and tries to engage with how, with restored sight, Gina becomes alternately fascinated and uncomfortable with the feeling of being watched—or being watched while remaining hidden, as in a scene where she blindfolds her husband as she videos their attempted tryst.

It’s an interesting moment that James and the movie keep returning to and reexamining through fractured lenses of heavy style, searching for a deeper meaning that never fully emerges. Questions linger throughout, many derived from a larger one: Is All I See Is You a portrait of a marriage in crisis, or a heightened, twisty thriller version of the same? This isn’t a criticism of a movie that “doesn’t know what it wants to be”—frankly, more movies should be this exploratory and uncertain about what genre they slot into. It’s when See gets decisive in its final moments that it falls apart—or, more accurately, dissolves into its own stylized mistiness. Lively has become an expert at creating the impression that at some point, the movie behind her will come together. All I See Is You comes closer than Adaline, but its adult intentions don’t go far enough.