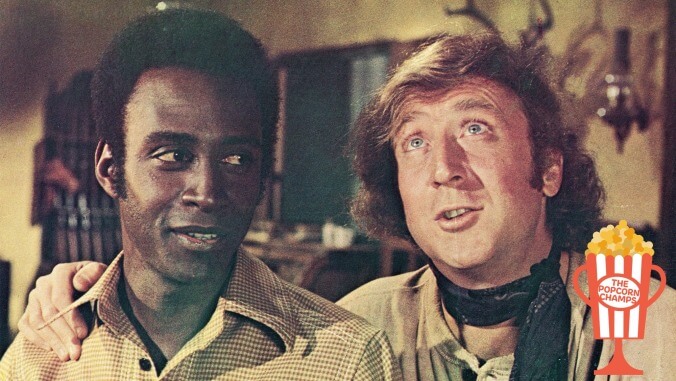

Blazing Saddles punched up—knocking out horses and a racist America in one swing

Image: Photo: Warner Bros.

John Wayne could’ve been in Blazing Saddles. When Mel Brooks was casting his absurdist Western parody, the film that ended up as the biggest hit of 1974, Brooks wanted Wayne to play the Waco Kid, the role that eventually went to Gene Wilder. Years later, Brooks told the story about the time Wayne read the Blazing Saddles script: “He says that he loves it—every beat, every line—but that it’s too blue, that it would disappoint his fans. He said, though, that he would be the first one in line to see it.”

If John Wayne is in Blazing Saddles, it’s a completely different movie. It’s probably not as funny; there’s no indication that Wayne could sell a joke with the same sort of quiet sparkle that Wilder always had. (Still, it’s fun to imagine John Wayne saying things like, “I must’ve killed more men than Cecil B. DeMille.”) But if Blazing Saddles has John Wayne, it might be an even more effective satire. John Wayne was the human representation of the Western—which made him, in some ways, the human representation of America. If he’d been willing to mercilessly skewer his own screen legacy, it would’ve gone down in history as one of the all-time great self-subversions.

By 1974, the Western, the dominant myth of American cinema, had already been subverted by plenty of other movies: Cat Ballou, Bonnie And Clyde, Sergio Leone’s Man With No Name trilogy, The Wild Bunch, Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid. It had been done, though never anywhere near as cartoonishly. But with John Wayne in the role, Blazing Saddles would’ve also subverted John Wayne’s own dumbass ideas about the way things should work.

Three years before Blazing Saddles came out, Wayne gave an interview to Playboy where he said stupid shit like this: “I believe in white supremacy until the blacks are educated to a point of responsibility.” And perhaps the greatest legacy of Blazing Saddles is that it’s all about that great American lie of white supremacy. Nearly all the white people in Mel Brooks’ movie are hooting, howling idiots, and nearly all of them are willing to destroy their own town if it means that they can continue to feel superior to the Black sheriff, the only person willing to help them. John Wayne told Mel Brooks that he loved the Blazing Saddles script. Maybe he did. But the Blazing Saddles script did not love John Wayne. In any case, instead of appearing in Blazing Saddles, Wayne spent 1974 making a barely-remembered Dirty Harry ripoff called McQ.

If you’re going to watch Blazing Saddles in 2019, your cringe muscles are going to get a workout. The film’s characters spray racial slurs all over the place. There are long, protracted, honestly funny-as-hell jokes built entirely around racial slurs. There are rape jokes, too. One of the film’s most celebrated scenes, Madeline Kahn’s seduction of Cleavon Little, is pretty much an extended running joke about German accents and dick sizes. (That scene’s final punchline was the one joke that Brooks was nervous enough to cut from the film: “I hate to disappoint you, ma’am, but you’re sucking on my arm.”)

Mel Brooks was understandably apprehensive about cramming his movie so full of racial slurs. But Richard Pryor, one of the film’s five co-writers, reassured him that it was okay, since the bad guys were the ones saying all the vile shit. (Brooks wanted Pryor to play the lead in the movie, but Warner Bros. didn’t think Pryor would be dependable enough to show up for work every day.) Pryor was right. Blazing Saddles is, in effect, a knowingly absurd comedy about how dumb racism is. A rapacious rich guy wants to run all the people out of a small town because the land’s about to be worth a lot of money, so he sends in a Black sheriff, knowing that the town’s residents will be too blinded by their own racism to look after their self-interests. Really, Blazing Saddles has as much to say about American capitalism as The Godfather does.

For months now, I’ve been looking at the history of hit movies, and only two of the films featured in this column before Blazing Saddles had any major characters of color: West Side Story, which was full of white actors wearing brown face to play Puerto Ricans, and Billy Jack, in which a white guy plays a character who’s half Native American. In the late ’60s, Sidney Poitier (who wasn’t in any of the movies covered in this column) became a major box office star, mostly by appearing in message movies about racism. But Poitier was literally the only one. Blazing Saddles isn’t just the first movie in this column with a Black lead. It’s the first with Black characters of any consequence at all.

The big debates happening in comedy right now are about whether comedians are allowed to joke about sensitive things—whether they’ll have their careers destroyed because they say the wrong things at the wrong time—and about the basic idea of punching down. There’s a persuasive argument that if you make jokes at the expense of people with less power than you, you’re an asshole. By that standard, Blazing Saddles has aged beautifully. It’s not perfect—the anarchic musical number at the end has more gay jokes than anyone needs—but for a 1974 comedy about race, it’s remarkably non-shitty.

And Blazing Saddles gets away with a lot because it’s also unbelievably funny. Mel Brooks anticipated the five-jokes-a-minute pace of something like The Simpsons by nearly two decades. Blazing Saddles is full of dumb jokes that achieve transcendence just because of how brutally unashamed they are and how quickly they keep coming. Some of those jokes are etched in the cultural memory now: Mongo knocking a horse out with one punch; Sheriff Bart kidnapping himself; a symphony of farts around a campfire. And they’re funny even if you know they’re coming. I don’t know how many times I’ve seen Blazing Saddles, but this time, I still had to pause at “Mongo only pawn in game of life.” I needed time to recover.

Blazing Saddles is also notable for its sheer, overwhelming love of chaos and for its willingness to utterly obliterate the fourth wall. Early in the film, the villain Hedley Lamarr turns to the camera and asks, “Where will I find such a man?” And then: “Why am I asking you?” By the time Blazing Saddles reaches its riotous conclusion, a gigantic fistfight has spilled out of the fictional town and onto the Warner Bros. lot. Slim Pickens has punched a guy out while declaring, “Piss on you! I’m workin’ for Mel Brooks!” And the characters have all gone to see Blazing Saddles in the movie theater.

Brooks was not the first screen comedian to make fun of the fact that he was a screen comedian. Playing the film’s crooked governor, he really just does a horny riff on Groucho Marx, a guy who’d been doing the same thing decades earlier. And Brooks was not the only person making insane, rule-shattering comedies in the ’70s; so, too, was his contemporary and fellow Groucho admirer Woody Allen. But scenes like that drawn-out brawl are way beyond anything that Allen was doing. They cross over into straight-up Bugs Bunny territory.

Blazing Saddles was a cultural phenomenon, but I’m not sure how much it really says about what was happening in American society, or even in the film industry, in 1974. It’s a comedy about racism that came out at a time when America was at least beginning to grapple with the fallout of the Jim Crow era. It’s a film that makes fart noises in the general direction of authority, and it hit theaters the same year that Richard Nixon resigned the presidency in disgrace. Maybe those things had something to do with its success. But I think Blazing Saddles made as much money as it did—about $120 million against a budget of less than $3 million—simply because it was so fucking funny.

Before Blazing Saddles, Mel Brooks had defused mines in World War II, told jokes at Borscht Belt resorts, pioneered sketch-comedy TV, and co-created a popular sitcom. He’d directed a couple of movies, including The Producers, but he’d never had a huge hit. But in 1974, Mel Brooks knew exactly what would make people laugh. On the Blazing Saddles set, Brooks’ best friend Gene Wilder pitched the idea of Young Frankenstein to him. Young Frankenstein came out by the end of 1974, and it was another of the year’s highest-grossing pictures. (On this list, it comes in at #4, behind Blazing Saddles, The Towering Inferno, and The Trial Of Billy Jack.)

Mel Brooks and Gene Wilder both went on to have legendary show business careers. Brooks won the full EGOT, and he still works now when he feels like it. Richard Pryor didn’t get to appear in Blazing Saddles with Wilder, but the two went on to make a string of successful buddy comedies. But Cleavon Little, the deft and charming Black actor who played the lead role in Blazing Saddles, never got to headline another film. Little had supporting roles in a few forgotten B-comedies and eventually starred in the second season of the early-’90s Fox sitcom True Colors. (He replaced a departing Frankie Faison.) Little died of stomach cancer in 1992. He was 53.

Judging by his work in Blazing Saddles, Cleavon Little was funny and talented enough to deserve a legendary career of his own. He never had the chance. In ’70s Hollywood, people were not offering lead roles in good movies to Black actors. As far as I can tell, Mel Brooks is the only person who ever really gave Cleavon Little an opportunity. That’s the problem with Hollywood history, and with American history in general: too many John Waynes, not enough Mel Brookses.

The contender: Other than the Mel Brooks joints, the blockbusters of 1974 were mostly disaster pictures: The Towering Inferno, Earthquake, Airport 1975. But the film that won Best Picture, and the year’s number six earner, was an actual straight-up classic, The Godfather: Part II.

In a way, it’s surprising that The Godfather: Part II wasn’t the same sort of cultural phenomenon that the original had been two years earlier. It’s just as great as the first film, and even though its story is split into two different narratives in different times, it does everything a sequel should do. It brings back all the best-loved characters of the first movie—even, thanks to flashbacks, the dead ones—and it expands the first film’s world, using that setting to tell richer and deeper stories.

In the case of The Godfather: Part II, it gives us Robert De Niro, maybe the only actor who could convincingly play the younger version of Vito Corleone, scraping and struggling and killing to pull his family out of poverty. And then it shows that same family, decades later, succumbing to the moral decay that may have always been inevitable. The Godfather: Part II is probably the most basic pick I could possibly make, but there’s a reason why some things are universally beloved.

Next time: This column will be taking the rest of November off, but it’ll be back in December with Jaws, the film that inaugurated a new era of blockbuster moviemaking. And around then, I’ll also have the 2019 editions of Age Of Heroes and A History Of Violence, my running columns about (respectively) superhero films and action cinema.

GET A.V.CLUB RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Pop culture obsessives writing for the pop culture obsessed.