As those paying attention will quickly realize, that someone is Ingrid (Ellen Dorrit Petersen), the movie’s main character. Ingrid has recently lost her vision, an affliction that began with what looked like a smudge on her contact lens and ended with blindness in both eyes. Now she spends every day indoors, alone with her thoughts, struggling with basic household tasks—a spilled meal is a minor crisis—and waiting for her husband (Henrik Rafaelsen) to get home from work. Most of the time is passed sitting by an open window and letting her mind wander; Ingrid’s hours are occupied with daydreams, nervous delusions, and the elaborate stories she conceives—and narrates—in her head. “It’s not important what’s real if I can visualize it clearly,” she says early on.

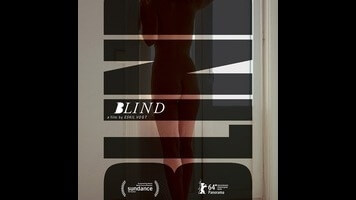

Blind is the feature directorial debut of Eskil Vogt, who co-wrote all three of countryman Joachim Trier’s movies—Reprise, Oslo, August 31st, and the forthcoming Louder Than Bombs—and proves here that he’s as responsible for the success (and the voice) of those films as his regular collaborator is. Vogt, who also penned the script, specializes in streams of consciousness; he builds movies around voice-over confessionals and montage overviews of lives both real and imagined. In Blind, he has great fun revising the narratives within the narrative, sometimes mid-scene. Early on, one of the subjects of Ingrid’s overactive imagination—Elin (Vera Vitali), a single mother who’s moved from Sweden to Norway—doesn’t bat an eye when her preteen son swaps genders in the space of a single cut. Neither does lonely porn addict Einar (Marius Kolbenstvedt) notice, several minutes later, when the café where he’s catching up with an old college buddy begins transforming periodically into a moving bus. By this point, Vogt has started openly and playfully bending the reality of his supporting characters’ worlds.

All this nesting-doll storytelling might feel hollow if Blind didn’t possess such a solid emotional foundation. It’s easy to get invested in Ingrid’s imaginary friends, fumbling for connection in an outside world she creates, because they’re reflections of her own anxieties—the fear that her disability is driving her husband into the arms of another woman. Self-pity might not sound like the most compelling of character traits, but Petersen, the film’s lanky Nordic star, finds the grace notes in Ingrid’s private struggle against despair. Vogt, likewise, takes what could have been a claustrophobic drag and opens it up through humor and insight. You’d have to be a bit nearsighted yourself to miss the movie’s charms.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.