More movies should take a lighthouse as their setting. For one thing, it assures some automatically striking imagery: a pale column rising from a cliff, stark against the blanket of blue above and the spiking unrest of the blue below. Plus, these lonely towers serve any number of symbolic functions. Man can be a lighthouse, instead of an island. The ocean can represent time and distance. The illumination at the top can cast a harsh beam of truth or a path forward through the dark. The lighthouse in Derek Cianfrance’s tony tearjerker The Light Between Oceans is a multipurpose symbol, amenable to the interpretive gymnastics of hustling English majors and film critics alike. But any reading that doesn’t incorporate World War I isn’t working hard enough.

“The war,” as characters invariably refer to it, has left Tom Sherbourne (Michael Fassbender) an empty vessel, as cavernously hollow as… well, take a guess. Haunted by what he’s seen and uncertain about how to move forward, Tom takes a solitary position manning the lighthouse on Janus Rock, just off the coast of Western Australia. “It’s quiet,” he says, somehow ignoring the wind whipping and the waves crashing all around him. Eventually, however, his cocoon of isolation is penetrated by a stranger: Isabel Graysmark (Alicia Vikander), a woman he meets in town and rather promptly falls in love with it. One scenic conversation on the bluff, the blazing red of a sunset as backdrop, is all it takes to make the feelings mutual. The lighthouse keeper has a wife, but there’s more heartache to come in both of their futures.

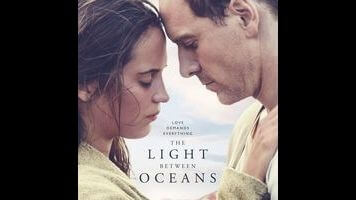

The Light Between Oceans sucks you in with the beauty of its landscapes, the elegance of its period detail, and the chemistry between two blindingly attractive stars who might actually be in love. (Fassbender and Vikander are, after all, an item in real life.) Yet for all its handsome pleasures, the film is also a curiously remote drama—great to gaze at from a distance, less so when studied up close. Part of the problem could be the challenge of adaptation. Cianfrance, of Blue Valentine and The Place Beyond The Pines, adapted Light from a 2012 bestseller by M.L. Stedman, and one can sense him struggling to contain its multitudes, to condense the full scope of its story to feature length.

Covered in a rush of montage, the sweeping romance on a windswept island is but a prelude to a major moral dilemma: A crying baby washes ashore in a dinghy, her father dead beside her, and Tom and Isabel—who have been unable to conceive—decide to keep the child as their own, not informing anyone on the mainland. This choice has repercussions that echo across the years—especially once Tom encounters a woman in town, played by Rachel Weisz, who lost her husband and infant at sea—and The Light Between Oceans keeps leaping forward to show how guilt and sorrow clings to its characters like moss on a rock. But the damage to their love story doesn’t land as hard as it might, because we barely know them as characters.

It’s a common problem of Cianfrance’s work, which always seems to be reaching for greatness at the expense of the good it could more realistically achieve. Adapting a years-spanning novel only seems to exacerbate his habit of privileging an ambitious structure—complete with significant jumps in chronology—over the nuts and bolts of scene-by-scene storytelling. As in his nonlinear bad romance Blue Valentine, Cianfrance looks for tragedy in the discrepancy between a couple’s blissful past and its ruined present, but the lack of concrete details about these people abstracts their drama. The Light Between Oceans paints Tom and Isabel’s romance in elliptical glances—a seductive strategy, but also one that leaves them feeling less like fully fleshed human beings than objects as symbolic as that lighthouse, the broken piano in their seaside home, or a metal rattle that becomes integral to the plot.

Maybe it’s just a literary issue. At a certain point, The Light Between Oceans seems almost single-minded in its pursuit of theme; by the time the nationality of the dead man in the boat is revealed, the film has made clear that we’re watching variations on survivor’s guilt—the idea that, in war and maybe life in general, staying alive (or emotionally fulfilled) is often a zero-sum game, dependent on choosing your own well-being over that of a stranger. Fassbender’s reliable, monolithic steeliness as a broken soldier makes sense in this context. But if the drama is purely abstract, Vikander didn’t get the memo. Even as her storyline takes on the baggage of metaphor, she plays the emotions real and raw and close—her Isabel visibly brightening as she reads her first love letter from Tom or crumbling as a terrible loss dawns upon her. Nothing symbolic there.