Blunt Talk offers further proof of Patrick Stewart’s brilliance

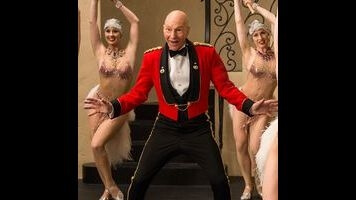

Sometimes it’s like Blunt Talk is daring itself to find a situation where Patrick Stewart cannot be funny, just to watch the old starship captain succeed anyway. Is Patrick Stewart funny when he’s unfolding a toilet seat cover? Yes. Is Patrick Stewart funny when he’s likening his own newsroom to “Stalin’s Russia”? He is. What about when he’s watching some preschoolers sing a song? Still funny. In his role as the narcissistic cable news host Walter Blunt, Stewart can do no wrong, and as such Blunt Talk leans on him to carry an otherwise hit-or-miss ensemble. He shoulders this burden with an élan that buoys the whole enterprise.

Blunt Talk is the creation of Bored To Death impresario Jonathan Ames, who developed this series after Seth MacFarlane (who serves as executive producer) expressed a desire to build a new show around Stewart. Walter Blunt bears some resemblance to Ted Danson’s magazine editor on Bored. Both men are drug-abusing media figures with an air of self-confidence and a trail of failed romances behind them. But where Danson’s character was inclined to hunker down with his vaporizer when events intruded on his idyll, Blunt is a happy warrior who believes he can always twist a narrative in his favor. This indefatigable spirit is showcased in the opening moments of Blunt Talk, when Blunt tries to talk himself out of a solicitation charge while hopping around on the roof of his vintage Jaguar.

That’s a zany setup, but Stewart also thrives in scenes that ask for less intensity. Although we only see glimpses of Blunt’s eponymous cable newsmagazine, the brief show-within-a-show scenes convincingly portray a TV host with the assuredness and creeping apathy that come from decades of experience. Blunt wraps up a segment on electronic child-tracking sensors by observing that he doesn’t much like the idea of “chipping” kids like they’re pets, “but I was also skeptical of the mobile phone, and I once did lose a dog.” With that, he shrugs off a complicated privacy issue so affably that it’s difficult not to laugh.