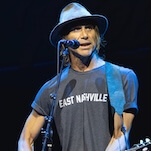

Bob Dylan, Blonde on Blonde

I've been itching to write one of

these ever since the Better Late Than Never feature started, 'cause I have a

doozy. Now, I know we all worry that we're missing something big. For some

reason—okay, let's just blame the Internet—we hold ourselves

responsible nowadays for knowing practically everything. The tribalism that

used to save us from, say, taking disco seriously, has gone away. Guys like

Nick Drake get dragged out of the archives and dropped on the college kid

must-know lists. Hell, people even talk about David Axelrod.

Except I'm not going to whip talk

about any of those people. Here's my confession: in all my life, and after

several years of writing about music, I have totally slept on Bob Dylan. I

don't mean that I didn't spend enough time on Dylan. I'm

saying that until a couple months ago, I had never played a Dylan record

straight through. I had zero interest in the guy. And I have no excuse.

It's not that I haven't had time:

I'm 34. It's not that I skipped the '60s: when I was a teenager in the pop

dustbowl of the late-'80s, I chewed through bands like the Beatles or the Dead.

And obviously I knew who the guy was. Dylan touched at least half the musicians

I ever listened to. He slipped weed to the Beatles and helped make the film Help!

so hilarious. He kicked Phil Ochs when he was down—and there's a guy I did listen to, thanks to my parents' copy of Pleasures of the Harbour. Even science fiction gives you no

escape: take Douglas Adams' mice quoting "Blowin' in the Wind," or the smarmy way

Cameron Crowe shoehorned The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan's sleeve

into Vanilla Sky, or—most bizarre of all—the Cylons

singing "All Along the Watchtower" last year on Battlestar

Galactica. Dylan's so heavy, he's intergalactic.

Baby boomers trip over themselves

talking about his genius. On HBO's In Treatment, Gabriel

Byrne enjoyed a quick smug moment of comparing him to Walt Whitman, and he's

not the first to stick Dylan in that canon. And that's his biggest problem: he

still belongs to the boomers. They discovered him, they claimed him as the

voice of their generation, and to this day they're insufferable about the guy.

One of my uncles—the one I stole so many Grateful Dead and Jethro Tull records

from, back in the day—put it this way: to get Dylan, you really had to

understand those times.

About Dylan, I'm an endless font of

ignorance. For my crash course I focused on 1966's Blonde on Blonde—one of the top ten greatest rock 'n

roll records ever, according to just about every critic over 50—and I prepped

with exactly two sources, the documentary No Direction Home, and Wikipedia. I learned some

pretty fascinating stuff. I had always pegged Dylan as an icon for

hippies—but I didn't know that he was the entertainment at Dr. Martin

Luther King's "I Have a Dream" speech. I knew the folkies got ticked when he made

it big and left behind the "topical song" movement, but hearing folks like Pete

Seeger talk about how a torch had been passed from Guthrie down to Dylan—and

how Dylan basically left it smoking in the Village somewhere, to be picked up

by pretty much no one of consequence—well, I can see how that hurt.

Most refreshing of all, I also

learned that Dylan's a bullshit artist. It's not because he kept making up his

biography, or pulled stunts like stealing all those Woody Guthrie records

before he came to New York, but because he's mastered the art of distorting

small facts to get to the big truth. And sometimes he gets caught. When someone

who knows him as well as Joan Baez nudges him off his pedestal, it reminds you

not to get too swept up in his mystique. In a clip in No Direction

Home, we see Dylan playing "Mr. Tambourine Man" for a workshop at the

Newport Folk Festival. As he unspools one endless, cosmic lyric after another,

you can almost catch him crack a smile—like he's saying, "I know, I

know." When you realize he's not sure where all this comes from either, it

makes you wonder about the rest. And that's about when you get hooked.

But Blonde on

Blonde has a pretty low bullshit content. For one thing, much of it's

about women, and when you go there for real, it's hard to get cocky. For

another, Dylan has said that Blonde on Blonde is "The closest I ever got to the sound I hear in my mind"—and the

honesty shows. Neither rushed nor lazy, it reminds

me of works like John Fahey's America, John Cassavetes' A Woman Under the Influence, or Dr. Seuss's One

Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish—a work with no sharp peaks or

ruts or concern for loose ends, that feels like one long train of thought.

Blonde on

Blonde has been praised for hopping across several genres—it's

pop, it's country, it's blues, it's surreal—and for how naturally the

styles blend into one another: after you get past the first two tracks, it

settles into a spacious, organic vibe that's far moodier than his previous

electric albums. The

record opens with "Rainy Day Women #12 & 35," which I started

skipping—it's too pat, and familiar from classic rock radio. It doesn't

hit its stride until track three, with "Visions of Johanna." You can hear a

harder, steadier version of it on the soundtrack album to No Direction

Home, and hearing that made me appreciate even more what a perfect

few minutes they caught here—the organic ramp-up, the way every lick from

the organ and guitar supports Dylan's voice, the lyrics that catch the

spotlight—"Mona Lisa musta had the highway

blues/You can tell by the way she smiles"—and the impressionistic lines

that stitch right into the absurd ones. It pulls off the great rock and roll

trick of sounding like the easiest, most natural thing in the world.