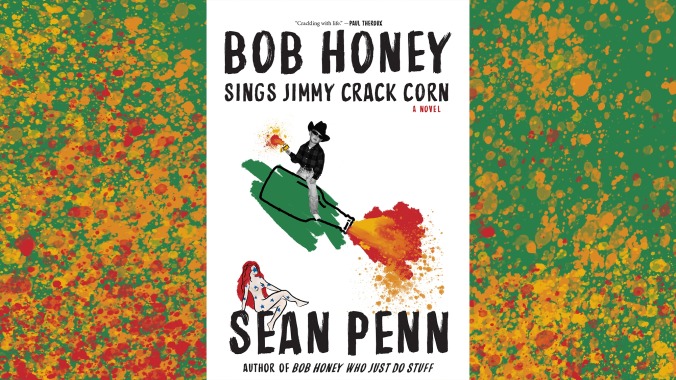

Bob Honey Sings Jimmy Crack Corn—and you won’t care—in Sean Penn’s second novel

Heaven help us, Hell spare us, Hollywood save us, Sean Penn has penned another novel, a sequel to last year’s Bob Honey Who Just Do Stuff. The actor’s flimsy fiction debut told the tale of the titular septic tank salesman who moonlights as an elderly death panel contract killer. Penn overstuffed that book’s 170 pages with thinly veiled commentaries on the war on terror, the federal government’s non-response to Hurricane Katrina, and a certain president—a “violently immature seventy-year-old boy-man with money and French vanilla cotton candy hair” nicknamed the Landlord. There were also alliterations aplenty, gratuitous Wallacian footnotes, and a particularly appalling epilogue in verse that refers to the #MeToo movement as “this infantilizing term of the day… this toddlers’ crusade.”

For any literary-disaster schadenfreuders who might have missed it, critics were quick to dish out more filthy pans than a rush-hour Waffle House. One article deemed Bob Honey the “worst novel in human history”; another called it “repellent and stupid on so many levels.” Others (read: Penn’s pals) compared the actor’s prose to Kerouac, Bukowski, Hunter S. Thompson, and other talented men who sometimes slap-dashed together dumb, if not arguably dumber, books. Bob Honey isn’t the worst novel ever written—it’s not even the worst novel written by a Hollywood star—but it is, to quote the great Jeff Spicoli, bogus. Last year the author responded to his critics on Conan in true Pennsian fashion: “I’m 57, my pool’s heated—you can say anything you like.” So let me offer this: I’m 39, my backyard’s way too small to fit a pool, and Bob Honey Sings Jimmy Crack Corn is a project that feels as unnecessary as the further adventures of Sam Dawson.

Done with murdering innocent seniors, Honey—and Penn—doubles down on his rivalry with the man he calls that “flim-flamming finger-fucker,” the Landlord. He postmarks a threatening letter promising a swift and violent demise, signing off with a sassy “Tweet me, bitch. I dare you.” It’s a line that also appears in the first Bob Honey, a sign that Penn doesn’t have much of anything new to do or say that he didn’t explore before. Once again, there’s an abundance of affected, adolescent alliterations mined from the most marginal mysterium of his moth-eaten Merriam-Webster’s, like:

- “It can be a pickle to sort a predisposition from a premonition, a fickle folly from a formidable phrase, or a pursuer from the pursued.”

- “The pencil piñata of a person bleeds the confetti of plagiarized pop paeans.”

- “Sycophants of social media suck the conventional cock of censors’ sensibilities volunteering complicity in common thought—they’re bought!”

As in the previous novel, Phil Ochs lyrics trickle in, sublime, incongruous raindrops shoehorned into a murky narrative. There are additional weak attempts at #MeToo takedowns. More sadism, more drugs, more Pynchon-light conspiracy theories, more puerile descriptions of female anatomy, more racism masquerading as bold humor. Penn piles on yet two more references to Ennio Morricone’s “Gabriel’s Oboe,” one of the great classical compositions of the late 20th century. Is it a personal favorite? The tinny sound that throbs between his celluloid ears? Who knows? Who cares! By book’s end, the Landlord is dead, Bob is president, and you will have a headache.

Roll the credits, which, after the traditional shout-outs of thanks and praise, smear the Bob Honey haters. “To the critics of Bob Honey Who Just Do Stuff, the few who understood it, and the many who never read it,” Penn writes in the acknowledgments. “Without you, I may have shelved my typewriter for good.” If that’s the case, I take it all back. For the love of literature, read this book, or else Penn might write another.