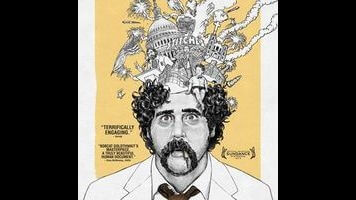

Bobcat Goldthwait pays tribute to a comedy mentor with Call Me Lucky

If it accomplishes nothing else, the new documentary Call Me Lucky should bring some welcome attention to a man who’s been under the radar for the past few decades, mostly by his own design. The film’s subject is Barry Crimmins, a stand-up comic who made a minor name for himself back in the ’80s, when he almost singlehandedly created the Boston comedy scene. One of the comics he helped discover was the very young Bobcat Goldthwait (whose nickname was inspired by Crimmins’ at the time, Bear Cat). Now Goldthwait has returned the favor by directing this biographical portrait, which reveals Crimmins as a figure who’s lionized by his peers, despite having been largely forgotten by the general public. As in the narrative films he’s made (Sleeping Dogs Lie, World’s Greatest Dad), Goldthwait stays behind the camera, but his long personal history with Crimmins provides him with access that no other filmmaker would likely have been able to get, given how ferociously the man guards his privacy.