Bogart goes boldly unhinged in the essential noir In A Lonely Place

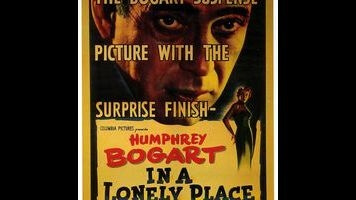

Nicholas Ray’s 1950 film noir masterpiece In A Lonely Place barely reaches the one-minute mark before its protagonist, Dixon Steele, tries to start a fight with a total stranger on the street. Since this as yet unidentified but clearly pugnacious character is played by Humphrey Bogart, it’s natural to assume that he’s a gangster, or a retired boxer, or maybe a private dick. The very next scene, however, reveals Dix to be a fairly successful Hollywood screenwriter—someone whose primary weapon is his imagination. Further reassessments will be required over the course of this remarkable film (it joins the Criterion collection on Tuesday, May 10), which doesn’t advance a plot so much as it poses a question: What sort of man is Dixon Steele? The 1947 source novel, written by Dorothy B. Hughes, provided one disturbing answer; the movie takes a radically different direction and somehow winds up at a more devastating destination.

Ironically, the most complicated narrative In A Lonely Place offers is the one that a young hat-check girl, Mildred, describes to Dix at his courtyard apartment. She’s just read the novel he’s been asked to adapt, and agrees to tell him the story so that he can decide, with minimal effort, whether or not to take the job. If this was a ploy to get into her pants—as Mildred herself suspects at one point—Dix apparently decides not to bother; she leaves without incident, and is seen doing so by Dix’s new neighbor, Laurel (Gloria Grahame). When Mildred’s corpse is found on the side of the road later that night, Laurel serves as Dix’s alibi, kicking off a passionate romance between the two. The cops continue to suspect and investigate Dix, however, and Laurel soon finds herself wondering, as evidence of her fella’s hair-trigger temper emerges, whether she may be in love with a murderous sociopath.

The film itself wonders, too, in numerous scenes that Laurel doesn’t even witness. Bogart would finally win an Oscar the following year, as Charlie Allnut in The African Queen, but In A Lonely Place arguably features his finest performance—at the very least, it’s his most unnerving. Dix demonstrates no emotional reaction, apart from mild irritation and amusement, when initially questioned about Mildred’s death; it’s as if he’s been informed that the car parked next to his earlier that night now sports a mysterious dent. He only gets exercised later, when discussing the case with friends (one of whom is a detective working the investigation). There’s something deeply discomfiting about seeing Bogart, the epitome of cool, practically lick his lips, wide-eyed, as he narrates a plausible scenario of Mildred being strangled by the driver of a moving vehicle. Whether or not Dix is describing his own actions—as Laurel admits, she has no idea what he may have done after she briefly saw him that night—there’s something seriously wrong with the guy.

Echoes of Hitchcock abound here. The basic scenario recalls Shadow Of A Doubt (substituting a lover for a hero-worshipping niece), and there’s a late reveal that nonetheless arrives earlier than expected, altering the tenor of the film’s climax significantly—a strategy that Hitch would employ a few years later in Vertigo. If anything, though, Ray maintains an even chillier remove. When Dix kisses Laurel at the height of her suspicion, she can’t keep her eyes closed, but Ray refrains from cutting to a close-up of her frightened expression, shooting the whole thing at a medium distance that heightens her feeling of being trapped. The film’s ambitious goal is to gradually make the question of whether or not Dix killed Mildred—which constitutes its entire narrative—seem almost irrelevant. When the answer arrives, it’s both too soon and much too late, and In A Lonely Place ends on a bleak, defeated note that makes its title an understatement.