Bohemian Rhapsody sings when it digs into Queen’s eccentric creative process

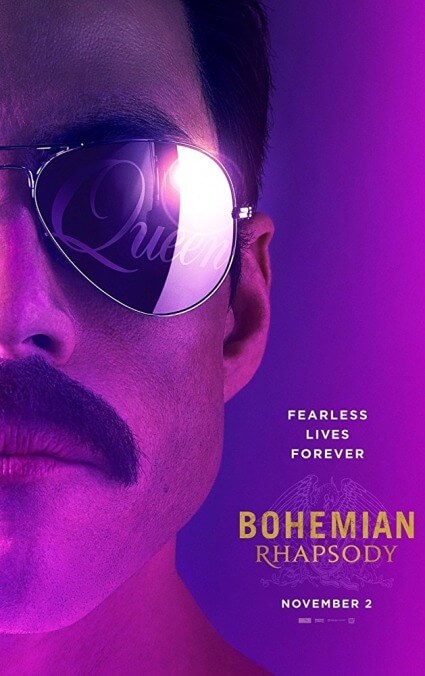

Many musical biopics depict their subjects’ output as monumentally, revolutionarily important. So there’s novelty to how much time Bohemian Rhapsody dedicates to the comparable strangeness of Queen’s songs. The movie puts forth that Freddie Mercury (Rami Malek) had a stage presence unlike any other singer, which helped vault the band to massive popularity. It also suggests that Mercury’s dynamism bought them a lot of leeway to follow their weirder impulses, even (or especially) in their biggest hits. Malek’s imitation does something similar for the movie, allowing the filmmakers to dig into the idiosyncrasies of Queen’s creative process.

This biography of Mercury (and to a much lesser extent, his bandmates) doesn’t chart any innovative narrative courses, or even pick up on the recent trend of zeroing in on a few important moments from an eventful career; it’s not the Queen equivalent of I’m Not There or Love & Mercy. But there are multiple scenes keyed to the creation of particular (and impressively disparate) tunes: the audience-participation genesis of “We Will Rock You,” the minimalist riff-based funk of “Another One Bites The Dust,” a frenzy of tape whirrs and clunks as the band pieces together the epic “Bohemian Rhapsody” itself, chased by a lengthy scene where EMI executive Ray Foster (Mike Myers) explains in no uncertain terms that he will not allow such an overlong monstrosity to be released as a single.

This scene is on-the-nose even before the former Wayne Campbell makes a wink-wink remark about how a different single choice will allow “kids [to] crank up the volume and bang their heads.” Also on-the-nose: the moment where Mercury actually says, out loud, “We need to get experimental,” the moment where Mercury announces that “We’ll mix genres, we’ll cross boundaries,” and the moment where someone tells Mercury, “You’ve got a gift.” Bohemian Rhapsody is not a subtle movie, nor is it a very good one. But it runs through the greatest hits with a lot of energy.

Whose energy that is, it’s harder to say. Malek certainly gives it his all as Mercury, affecting a toothy English accent and lip-syncing with sweaty abandon; the performance may feel more imitative than revelatory, but even having the presence to hold the screen as Mercury for an entire film is something of an achievement. The movie’s behind-the-camera situation, meanwhile, justifies every vague use of “the filmmakers,” as Bryan Singer directed for several months before he was fired and replaced by Dexter Fletcher, who’s already at work on another ’70s-centric musical biopic, this one about Elton John.

Maybe a future commentary track can clarify whether the multiple cat reaction shots were in Singer’s original storyboards or unique to Fletcher’s vision of the film. As-is, there aren’t many visible seams. The movie follows Mercury from light conflict with his Parsi parents to his fateful meeting with guitarist Brian May (Gwilym Lee), bassist John Deacon (Joseph Mazzello), and drummer Roger Taylor (Ben Hardy) to a standard rise-fall-rise trajectory. The filmmakers are consistently more expressive working in montage than they are during the more dramatic scenes. It turns out that Singer is better at conceiving moments of reflection and unexpected grace for superheroes than he is for a real-life rock star.

Early worries that Bohemian Rhapsody would downplay Mercury’s sexual orientation turn out to be relatively unfounded; when Mercury tries to tell his long-time romantic partner Mary Austin (Lucy Boynton) that he’s bisexual, she gently but firmly dismisses it as a half-truth, and Mercury doesn’t really question her perception, though he clearly adores her. It’s later implied that the loneliness of life as a sorta-closeted man (even an enormously famous one who performs with flamboyant abandon) leads to Mercury being manipulated by his personal manager and occasional lover Paul Prenter (Allen Leech). All of these relationships, as well as Mercury’s eventual AIDS diagnosis, are compelling in an efficient, boilerplate sort of way—more self-consciously dramatized from the biopic songbook than fully felt or inventively reimagined.

Eventually, the movie circles back to a climactic performance at Live Aid, the massive 1985 famine-relief benefit concert to which Queen was added late in the game. The set is reproduced nearly in full, with a lot of momentum and excitement (and perhaps too many cutaways to a massive computer-generated crowd). Like a lot of depictions of rock music on film, Bohemian Rhapsody lacks both the stylistic daring of a music video and the outright euphoria of a proper musical, but it gets closer to both with the Live Aid sequence, sort of a cinematic equivalent of that old saw about bands who might sound underwhelming or off-putting on their studio records: You really gotta see ’em live. Bohemian Rhapsody’s one bold gambit is its willingness to minimize the importance of the albums (the movie is outright dismissive of plenty of tracks) or songwriting (often depicted as extremely assured screwing around) in favor of presenting this mismatched band as an experience. In the best scenes, the filmmakers make the case that Queen’s musical decisions grew out of the musicians’ restless inability to fit in with either pop conventional wisdom or, sometimes, each other. The rest of the movie fits in all too well.