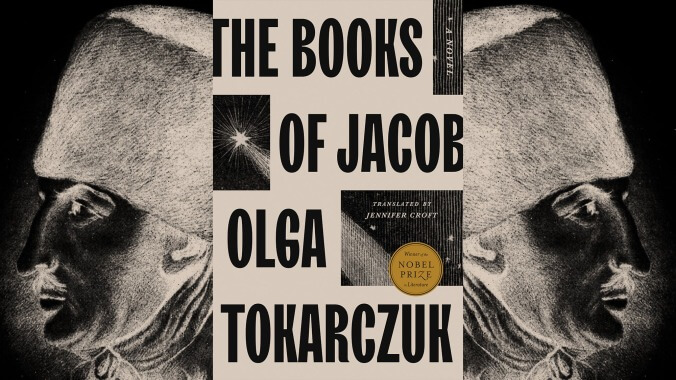

In The Books Of Jacob, a Nobel laureate tells the epic story of a self-proclaimed messiah

Originally published in Polish in 2014, Olga Tokarczuk’s 965-page magnum opus at last makes its way into English

Image: Graphic: Natalie Peeples

Books are always arriving at the wrong time in Olga Tokarczuk’s The Books Of Jacob. The 18th-century Eastern Europe and Mediterranean through which this novel charts its course is a thoroughly multilingual environment. It’s not uncommon for characters to juggle Polish, German, Yiddish, Turkish, and Ruthenian within a single conversation. Accordingly, writing moves at a much slower pace, and printing is often a matter of great personal cost. Official edicts take years before they’re translated into popular language, and heretical books are subject to censure and often burned. The Books Of Jacob also details prescient volumes that arrive too soon, and for that amount to prophecy. It’s appropriate then, that it should take a monumental amount of time, and deft translation work from Jennifer Croft, for this 965-page novel, which first appeared in the author’s native Poland in 2014, to make its way into English.

It comes with the recommendation of the Nobel Committee for Literature—which, in another example of bibliographic mistiming, retroactively awarded Tokarczuk the 2018 prize a year late, due to resignations at the Swedish Academy amid a #MeToo scandal. In the Anglosphere, little of Tokarczuk’s work had been made widely available at that time, and most reporting on the prize was devoted instead to 2019 laureate Peter Handke’s controversial support for Slobodan Milošević. The Books Of Jacob appearing now feels like a long-promised setting to rights, an occasion for English readers to experience a genuine global artistic event: the publication of a genre-broadening contribution to the historical novel.

For her subject matter Tokarczuk takes on the real-world figure of Jacob Frank, a Polish Jew who, beginning in the 1750s, claimed to be a messiah before leading his followers down a path of mysticism, apostasy, and often-dangerous adventure. Believed to be a reincarnation of the previous messianic claimant, Sabbatai Tzvi, Jacob Frank preaches a doctrine of liberation from the Talmud, Mosaic Law, and nearly every other cornerstone of conventional Jewish faith. In extraordinary times, according to Frank’s teaching, it falls to the messiah to transgress the old law and so herald the new. Scandalously, the Frankists convert to Christianity and face excommunication from the Jewish community. Only shortly thereafter, they’re accused of Christian heresy, and Frank is put in front of a tribunal. Religious disputation and changing political winds then find these true believers alternately embraced, embattled, imprisoned, or on the road within the roughly 40-year span of The Books Of Jacob’s principal action.

The magic of the novel is that an encyclopedically researched account of a fringe schismatic denomination from nearly three centuries ago should feel so wildly contemporary. At times, the long and abstract asides on Kabbalism can seem remote from modern readers’ concerns. But when the true believers establish their communitarian peasants’ republic on the site of a town abandoned by its previous inhabitants after a bout of plague, something of our own times’ apocalypse is brought into relief. The Books Of Jacob is studded with similarly affecting moments, in which both the proximity and the distance of the past are thrillingly, simultaneously affirmed.

In a certain sense, Tokarczuk is concerned with letting you see the sweat on her product. The book concludes with a note on sources, and every period detail reads as faultlessly placed. The Books Of Jacob projects verisimilitude. Simultaneously, fictional composites exist alongside the historical personalities. Novelistic convention is subtle here, but ever-present. Frequently present, too, are reproduced paintings, lithographs, maps, and long blocks of direct quotation. Archival documents and pure invention share page space in a way that invites commentary and endless interpretation, putting into formal play the very questions of allegorical and mystical meaning that feature as the novel’s content.

Reality becomes increasingly difficult to parse from fabrication, and the power of narrative, it’s clear, lies in the resonances and connections that artifice can reveal between known facts. As one late passage has it, “Over time, moments occur that are very similar to one another. The threads of time have their knots and tangles, and every so often there is a symmetry, every once in a while something repeats, as if refrains and motifs were controlling them, a troubling thing to notice.”

Within the Enlightenment period that Tokarczuk presents, much progress was made in the study of optics. Jacob Frank’s preaching is depicted alongside Benjamin Franklin’s invention of the bifocal, the publication of Newton’s physical observations of light, and the popularization in Europe of the camera obscura—a technological precursor of the photograph. The suggestiveness of this choice in images for The Books Of Jacob is rich, as light and its manipulation come increasingly to be explained in the terms of the incipient Scientific Revolution. One story that the book has to tell is then of the undecidable encounter between eons-old faith and a growing rationalism.

At the same time, it’s a virtue of mysticism to be contradictory and puzzling, and in Jacob Frank, Tokarczuk has a hugely confounding figure. Most of the novel observes him in a broad third-person. Occasionally, there are diaristic asides from Frank’s disciple and biographer, Nahman of Busk. Perhaps the most interesting and reaching of the perspectives on offer here is that of Yente, Jacob Frank’s comatose grandmother: Hovering somewhere between life and death after a debacle involving an amulet, she dispassionately observes the entirety of the plot as a disembodied spirit. She synthesizes the diversity of otherwise random events, cutting out of them an intelligible figure. In this way she most resembles the author, as The Books Of Jacob’s art is restoring and activating that recognizably human movement that’s always present beneath the inert, static material of facts.

The Books Of Jacob’s choices can sometimes be daunting. The book’s scale; its hugely populous cast of named characters; its reverse-ordered page numbers, done in honor of Hebrew convention; and the intense pitch of human suffering so often achieved—it all makes for less than hospitable reading. In many ways, it’s the contents of the past itself that’s the source of this difficulty—obdurate as it is, and liable to unpredictable change. If there’s one thing that Joseph Frank, the messiah, is concerned with imparting, it’s the provisionality of all earthly things. In her clear-sighted rendering of enormous historical momentum, pitilessly displaying the dissolution of both national borders and whole systems of belief, Olga Tokarczuk achieves much the same objective.

Author photo: Lukasz Giza

Drew Dickerson lives in Providence, Rhode Island.