Boppin’ them on the head: 17 terrifying bunnies from pop culture

Not all bunnies are cute. Here are 17 terrifying rabbits from pop culture.

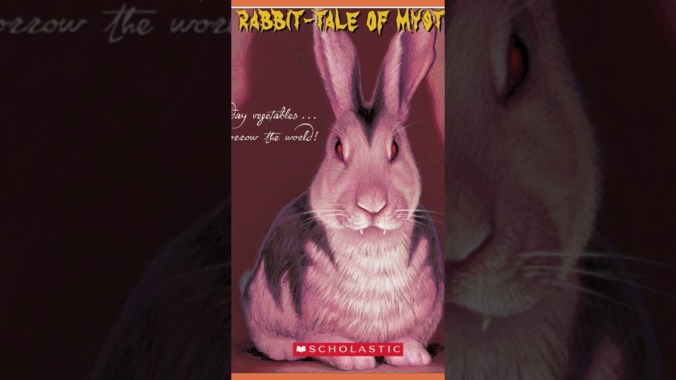

There’s nothing less likely to be evil than an adorable, fuzzy little bunny—or is there? Every year, Easter rolls around and providing both person-sized rabbits giving out candy and animated bunnies twitching their noses. But something about all that fuzzy innocence has inspired some creators to paint it black—to make that which is cute, evil. In Bunnicula, a young-adult novel version of this horror, a pet dog describes the household’s newest arrival, a vampiric bunny. (The protagonists keep finding eerily white vegetables, suggesting Bunnicula has sucked them dry. This does not, however, make the vegetables into more bunny vampires, though they are “staked” with toothpicks just in case.) The novel is more tea-cozy domestic comedy than horror story; it allows Chester the cat to believe in Bunnicula’s vampiric powers, while otherwise portraying him as a silent, odd, fanged bunny who has a weird way of eating vegetables. Bunnicula ends up squarely in the realm of dark comedy—even though Bunnicula is mostly harmless, the bunny’s powers are never explained. The novel becomes about living with the mystery (as did the several Bunnicula books that followed), rather than solving it.

The Muppets have never shied away from the macabre if they could milk it for laughs, and this featuring a rabbit-monster singing “Stand By Me” is no exception. After using Ben E. King’s classic song as a way to lure in his prey, the singing Muppet (who only introduces itself by saying: “Hi, I’m a bunny!”) smashes victims on the head with a giant carrot before gobbling them up. While the “bunny” is less scary than goofy, the clip still showcases the wholesale slaughter of innocents, including one of the defenseless animals begging for its life. “Stand By Me” is either hilarious or horrifying, depending on who’s watching, and the coda featuring comical curmudgeons Statler and Waldorf doesn’t dispel the feeling that it comes from the darkest corners of the Henson vault.

The makers of the direct-to-video slasher film Easter Bunny, Kill! Kill! arrived late to the holiday-themed horror genre, after many earlier movies (Christmas Evil; Silent Night, Deadly Night; Santa’s Slay) had already beaten the novelty value out of seeing a guy in a Santa suit seriously misbehaving. EBKK features a single mother and her mentally challenged, Easter-loving son, whose only friend is his pet bunny. Meanwhile, somebody in their neighborhood is running around jacking convenience stores while wearing a decidedly un-cute rabbit mask. The two plot threads converge when Mom’s new boyfriend invites a conga line of lowlifes into the house to spoil the kid’s holiday. They are met by an angry, avenging spirit in the rabbit mask, who uses a variety of implements to paint the walls red with their blood, rather than coloring eggs.

In both book and film form, General Woundwort, the leader of a fascist dictatorship rabbit warren in Watership Down, is a terrifying dude. He keeps rabbits in cowering subjugation, essentially holds sway over everyone by being huge and scary-looking, and isn’t afraid of taking on a dog should the moment arise. He’s the main villain of Richard Adams’ novel, and the animated-film adaptation of the book gave the general a raggedy look that let viewers know he’d been in thousands of fights—and won all of them—so the heroes had best not come at him unless they had the goods to back it up. Long-standing rumors—denied by Adams—speculate that the warrens of Watership Down are based on various nations’ responses to the threat of Nazism. It’s easy to see why those theories arose in the first place: For all intents and purposes, General Woundwort makes a compelling Hitler figure in rabbit form, a creature who will trade all freedom for the promise of security and must be stopped at all costs.

Sure, it’s a comedy video, but the Easter Bunny of “The Easter Bunny Hates You” is still pretty scary. For example, a woman spots the title bunny beating someone up across the street and turns away in horror—but when she turns back, he’s lurking right in her window. If you’re at just the right, impressionable age, that could be some premium nightmare fuel. And even if you’re not, do you really want to contemplate a world where a man-sized rabbit runs rampant through the city, beating the shit out of people every spring?

When he wrote his science-fiction novel The Year Of The Angry Rabbit, Australian author Russell Braddon understood that the idea of giant, mutant rabbits running wild over the countryside was an inherently amusing one. He penned the book with tongue firmly in cheek, as more of a social and political satire than anything else. Naturally, when Hollywood got its hands on the property, someone somewhere (presumably director William F. Claxton, producer A.C. Lyles, or screenwriters Don Holliday and Gene R. Kearney) said, “Killer rabbits?! Scary!” and proceeded to more or less approach the idea completely straight-faced (starring Janet Leigh, no less). That, of course, is what makes Night Of The Lepus so terrible—and so terrific. Few cult movies are as purely enjoyable to watch as this one, as normal-sized rabbits wreak havoc on miniature sets, interspersed with occasional footage of people in rabbit costumes battling the other actors. The only problem here is that MGM got rid of the original title, the absolutely perfect Rabbits.

Inspired by a carving on the façade of Notre-Dame (a knight fleeing from a rabbit, which represents cowardice), the white rabbit that guards the Cave Of Caerbannog is a perfect bit of comic misdirection in a film that proves to be hilariously self-aware. Though Tim The Enchanter’s description of the beast strikes fear into King Arthur’s band of Grail-seekers (Robin even soils his armor), once the seemingly harmless little bunny appears, they all presume it’s a mistake. Suddenly full of confidence, Arthur orders Bors (director Terry Gilliam, in a cameo appearance) to swiftly dispatch the rabbit—except the little creature turns lethal and immediately severs Bors’ head. An all-out assault on the beast only gets more men viciously killed, leading to Arthur’s infamous “Run away!” order. Unable to slay the rabbit in hand-to-hand combat, the party resorts to using one of Brother Maynard’s relics, and another lasting symbol from the film: The Holy Hand Grenade Of Antioch, a device that mocks the globus cruciger as a Christian symbol of authority prevalent in the Middle Ages.

In “The Endomorph,” an episode of the TV anthology series Metal Hurlant Chronicles, mankind is at war with a race of monsters bent on wiping out our entire species. In a bunker, a few survivors cast nervous looks at a little boy cuddling his pet bunny and talk about how they need to make it to “the Mechadrome,” which has the power to transform “the young and innocent” into “a Golem” large and ferocious enough to become mankind’s savior and champion. In the end, all the adults are killed off and the leader of the genocidal monsters faces down the little boy a few feet from the Mechadrome, taunting him for having failed to reach his destination. But in the heat of battle and the thrill of apparent victory, the general has failed to anticipate the likelihood of a twist ending. Suddenly, the bunny rabbit, now the size of King Kong, comes lumbering out of the mists. The conquering armies are soon reduced to crumbs beneath the toes of his giant, stomping bunny feet.

A gangster/heist picture with a rough-and-tumble cast including Ray Winstone, Ian McShane, and Ben Kingsley may be the last place anyone would expect to find a scary bunny, but director Jonathan Glazer and his writers stuck one into Sexy Beast anyway. Winstone’s Gal Dove, a retired criminal living the good life in a Spanish villa, receives word that his fearsome former colleague Don Logan is en route to recruit him for one last job. After a day of hunting rabbits, Gal dozes off and dreams of being stalked by a hideous bunny-demon wielding an automatic weapon. Although a somewhat incongruous moment in the film, as anxiety-conjured images go, it’s definitely a memorable one.

In Bill & Ted’s Bogus Journey, the murdered duo find themselves tossed into a hell of their own making, experiencing an eternity of terrors conjured from the recesses of their own minds. For Keanu Reeves’ Ted “Theodore” Logan, his tormentor arrives in the form of the Easter Bunny—a bouncing, squawking hare who’s an embodiment of all the repressed shame of Ted’s misspent childhood, as well as just a generally creepy little fucker. Considering the Easter Bunny is a sanctioned home intruder with an eerily unexplained access to brightly colored eggs who’s seemingly granted his magical powers by the spilling of Christ’s blood, Ted is right to be scared of him.

Putting a family of clothes-wearing, human-sized rabbits into a three-camera sitcom sounds like a recipe for absurdist humor. Perhaps not surprisingly, it becomes the stuff of nightmares in David Lynch’s hands. Just one of many unsettling non sequiturs nestled into the three-hour mindfuck that is Inland Empire, the untitled sketch depicts a suited hare entering a living-room set and exchanging nonsensical banter with his wife and child. (The laugh track responds uproariously to such random lines as “What time is it?” and “There have been no calls today.”) Maybe it’s the typically Lynchian soundtrack, or the rough texture of the digital imagery, or the cutaways to a woman sobbing on the other side of the television screen, but the whole sequence elicits a vague, overwhelming unease. Wherever the dread comes from, “Bunny, I’m Home”—as we’ve chosen to call it—is the most uncomfortable distortion of sitcom tropes since the Rodney Dangerfield scenes in Natural Born Killers. And even those didn’t feature frighteningly blank-faced rabbit people.

Centered on a family held hostage by a mischievous little boy with reality-altering powers, Joe Dante’s contribution to the Twilight Zone movie is probably best appreciated as a showcase for some truly inspired Rob Bottin special-effects work. Plenty of wildly imaginative set pieces are packed into that penultimate segment, but for sheer, primal effect, nothing beats the scene in which Kevin McCarthy performs his famous hat trick. The money shot of the nervous, amateur illusionist yanking that monstrous rabbit creature out of his tiny black hat probably ruined magic shows for more than a few traumatized kids in the audience. Yet the real power of the scene lies in the suspense of its build-up, in the sweaty nervousness McCarthy conveys as he waits to see what his demonic little relative has waiting for him. The beastly creature itself is just a bonus.

The members of the experimental pop outfit Animal Collective specialize in merging the pleasant with the unsettling. The band’s sound draws equally on sunshiny Beach Boys harmonies and warped, acid-freakout sound manipulation; the video for “Little Fang” by AC offshoot Avey Tare’s Slasher Flicks looks like a Sesame Street segment directed by Rob Zombie. In 2004, Tare laid the groundwork for his video depicting a day with the spawn of Captain Spaulding by donning a ratty bunny suit and hopping around like a maniac. A psychedelic retelling of “The Tortoise And The Hare,” the “Who Could Win A Rabbit” video pits that fable’s adversaries against one another in a road race that the hare just can’t win, all feral taunting and attempts to choke his rival notwithstanding. But Tare’s character doesn’t get truly frightening until the coda: Chopped up and feasted upon by the tortoise, the hare has his head plated and his mouth stuffed, one of the most disturbing images served up by a band that can’t get enough of monsters and horror-movie goop.

This monstrous bunny from Donnie Darko is, perhaps, the iconic terrifying bunny: “Frank,” a human-sized figure with a rabbit mask, appears to Jake Gyllenhaal’s Donnie in dreams and visions with portents of coming doom. At the beginning of the film, he tells Donnie when the world will end, and later coerces him into burning down his teacher’s house. The film’s cult status relies, to some degree, on its sudden, switchback ending—Frank turns out to be someone’s Halloween costume, and Donnie was dead the whole time. The movie portends that every living thing dies alone, but hopefully, no living thing has to die with that horrific bunny as the last thing they see. Quick, cue up Gary Jules’ version of “Mad World.”

The films of cult Czech director Jan Švankmajer, particularly Alice, play it loose and free with Lewis Carroll’s hallucinatory vision from Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland, but the hallmarks are all present: a strangely Abe Lincoln-like Mad Hatter, the decapitation-crazed Queen, and, of course, the White Rabbit. Alice first meets the little monster as a taxidermied eyesore in a glass box. The live-action Alice sees the rabbit and this phantasmagorical nightmare world through stop-motion animation, making the whole experience surreal and disjointed. The on-the-lam rabbit, dressed in oddly foppish attire, constantly leaks sawdust stuffing as he rushes to meet the queen. With Alice in hot pursuit and zero malice, the White Rabbit is for no discernible reason a psychopathic asshole to her and anyone he meets. He pelts her with rocks, cuts her with weird objects, and chops off heads. He’s a mean little beastie. By the way, never let a friend talk you into watching it, or any of Švankmajer’s work, on hallucinogens.

The White Rabbit isn’t the only character from Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland and Through The Looking-Glass that received an evil reboot: The March Hare, though always somewhat mad, becomes downright evil in Syfy’s miniseries Alice. The series reimagines Wonderland for the present day; the March Hare becomes Mad March, a porcelain-headed cyborg assassin with a marked Brooklyn accent. He tortures the Mad Hatter until the Hatter punches him in his repurposed cookie-jar head.

Savage Steve Holland somehow conned a major studio and an already dramatic-leaning John Cusack into his film One Crazy Summer, a looking glass of random chaos that plays like an acid-fried Zucker Brothers pilot. The introduction to One Crazy Summer is, literally, a deranged, animated bunny popping out of the Warner Bros. logo, as the audience is plunged into the id of the struggling cartoonist and basketball prodigy Hoops McCann (Cusack), animated by his own hand as a lumbering rhino. The Rhino sets off to find “love,” portrayed as a diapered, blind baby cupid with sunglasses. Immediately into his journey, the Rhino meets the “cute and fuzzy bunny gang” who, he assumes in his good-guy naiveté, will help him find love. The drunken and hostile bunnies instead beat and insult him, plaguing him throughout the film until—in ’80s movie logic—McCann saves singer Demi Moore’s family home, and true love defeats the cute and fuzzy bunny gang—for now.

GET A.V.CLUB RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Pop culture obsessives writing for the pop culture obsessed.