Boris Without Béatrice struggles to modernize a myth

King Tantalus, from whose name we get tantalize, was condemned to spend eternity in the lowest level of the Ancient Greek underworld, up to his chin in waters that drained whenever he opened his mouth to drink, while branches of delicious fruit hung low over his head, swaying out of reach whenever he raised his hand. This was cruel—though, to be fair, Tantalus was being punished for chopping up his son, Pelops, the namesake of the Peloponnese, and trying to serve the cooked pieces to the gods, who were only able to glue Pelops back together and revive him after Demeter had scarfed down one of his shoulders. Just as with the serial killer and con man Sisyphus, who was cursed to push a boulder up an incline only to watch it roll back down, it’s the divine punishment that gets remembered, but not the crime. But they are pessimistically inseparable in Greek myth, which told of a world of hubristic, psychotic mortals and mean, moody gods.

Denis Côté (Vic + Flo Saw A Bear, Curling) frames the deadpan and slightly surreal Boris Without Béatrice as some sort of modern-day take on the Tantalus myth, but it might be more accurate to call it the French-Canadian writer-director’s homage to the mythological and audiovisual preoccupations of Jean-Luc Godard: the blank walls, the susurrating foliage, the reciting women, the random gunshots, the tracking shots through factory floors, the figures framed through balcony doors, the car stuff. Leaving behind the working-class, Quebecois-backwater settings of his previous fiction films, Côté pictures the cursed king as one Boris Malinovsky (James Hyndman), a prickly, philandering Russian-Canadian industrialist; the Beatrice of the title is his catatonically depressed wife (Simone-Élise Girard), who is taking an extended “leave of absence” from a senior government position at the couple’s country home.

While she spends her days staring out the window, looked after by a full-time caretaker (Isolda Dychauk), Boris carries on with what one presumes must be business as usual: scolding neighbors and cashiers, meeting up in hotels with his mistress (Dounia Sichov), driving around in a black Mercedes. Enter an enigmatic, sherwani-wearing stranger (the great French actor Denis Lavant), who invites Boris to the sort of late-night, abandoned-rock-quarry rendezvous usually associated with mob hits to inform him that it’s his selfishness that’s making Beatrice sick. This might not be the most exciting way update the mythic cycle of taboo, frustration, and cosmic jurisprudence; the story of Tantalus’ punishment, which gets recited here, is a shockingly exaggerated allegory of guilt, the king left eternally unfulfilled by his crime.

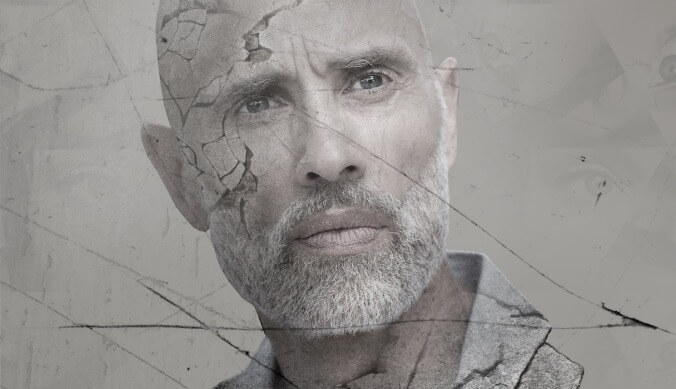

Yet it comes close to turning into a cogent statement on free-market mores, with an antihero who refuses to share his success, but feels responsibility for his failures. With his imposing Yul Brynner chrome dome and perfect air of superiority, Hyndman creates a strong focal point for Côté’s otherwise caustic and affected style. But the movie is undermined by its conceptual maundering and impersonality; it can be clinical and opaque one scene, conventional and over-determined the next. The simple truth is that, unlike the Godard films it loosely models itself on—very personally developed collisions of classic texts, relationships, and money like Contempt, King Lear, Hail Mary, and the underrated Oh, Woe Is Me—Boris Without Béatrice never feels like the work of an artist who actually believes in everything he’s doing.