Both of Frank Ocean’s new albums are more singular than you think

For all of the immersive experiences surrounding a new Frank Ocean record—make that two new Frank Ocean records—the end product is surprisingly singular. In his visual album, Endless, stark black and white footage shows three different versions of him simultaneously constructing something in a warehouse. None of the Franks are in any kind of hurry; their faces remain stoic, their working pace measured (they frequently check their phones) until they’ve sawed, spray-painted, and assembled a spiral staircase in the middle of the room. Once the project is complete, one of them nonchalantly ascends. The film starts over before he gets to the top, and the credits roll.

It’s an obvious message on the perfectionist work habits of a musician like Ocean, whose follow-up to 2012’s Channel Orange has been hinted at then delayed many times over. As stated by artist Tom Sachs (who was a consultant for the project) in his recent explanation of Endless, creating art as meticulous as Ocean’s “simply takes time.”

That idea alone would be slightly fascinating if not for Endless’ length. At almost 45 minutes with only the subtlest of changes in tone and action, the video becomes a chore to sit through. And the music—the “album” half of the equation—only makes the visual component more interesting in fits and starts. Because Ocean’s cinematic abstractions are already so minimal, it’s the more fully developed compositions that prove to be most arresting, especially the lush yet pained rendition of The Isley Brothers’ “(At Your Best) You Are Love” that kick-starts the moment when Ocean gets to work. The opening momentum carries through “Alabama,” where, in multilayered vocals, he remembers family dysfunction while growing up in New Orleans as well as being honest through his writing rather than his interactions with people. Though brief, it’s one of the few tracks on Endless that feels both lyrically and musically complete. As the album progresses, however, it only renders the accompanying short film more abstract and boring, with undercooked ambience, half-finished verses, and robotic descriptions of Apple products.

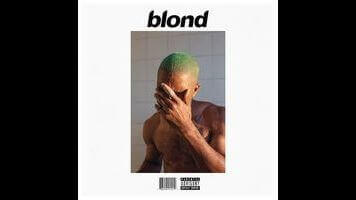

Of course, no one thought Endless would be the final result of Ocean’s creative journey over the past four years, and if the visual album is all about process (and perhaps contractual obligation), the main course, Blond(e), has deeper roots in a product. For the most part, the musicality—much sparser than the maximalist sonic feasts of his earlier work—still holds the same synesthetic power of the past, even for those who don’t claim to have the ability to see sounds. The palm-muted guitar of “Ivy” has a glow that can best be described as burnt orange, the piano keys of “Pink + White” (featuring Beyoncé) alternately light up in the colors of the song title, and the staccato chords of “Nights” spark in bursts of neon purple.

Even the more transitional tracks—interludes not labeled as such are a staple of Ocean’s at this point—have a deliberate warmth. At first, “Be Yourself,” “Facebook Story,” and the hidden back half of rambling closer “Futura Free” only seemed unified in that they’re spoken recordings of people who aren’t Ocean: The first is a concerned anti-drug phone call from his friend’s mother, the second a social-media breakup tale from French producer SebastiAn, and the third a roughly recorded series of interviews with Ocean’s little brother, Ryan. Upon closer inspection, the same sentimental electric-piano line links each fragment, stitching them together into an emotionally comforting quilt. Suddenly, they’re all brief respites from Blonde’s preoccupation with romantic longing.

And that’s where Blonde and Endless start to dovetail in their respective aesthetics, with the former’s lyrics having the same type of narrow focus as the latter’s visuals. Despite the pop-up shops, despite the differing tracklists, despite the 360-page zine, despite the alternate masculine/feminine titles, and despite the loaded context that already comes with such a hyped release outside of the immersive experience, Blonde stays focused almost exclusively on one thing: love of the unrequited or secretive variety. At first, it appears this won’t be the case. Over wobbly bass, opener and first single “Nikes” muses on a variety of topics, from groupies wanting a stable relationship to dead rappers and the merits/diminishing returns of hedonism. But by the time the party clears out, it’s just Ocean left standing among the piles of glitter, addressing a lover who won’t love him back. “We’re not in love, but I’ll make love to you,” he sings. “I’ll mean something to you.”

That more or less becomes a mantra for the rest of the album. Whether he’s writing about the same person or several people from his past, there’s no long-term follow-through to any of the romance. In “Ivy,” neither party (both of them teenagers) is mature enough to vocally recognize his true feelings. Later on in the soft blues of “Self Control,” Ocean laments how his ex (or maybe part-time) lover views him as someone to be kept hidden and fleetingly enjoyed, going as far to compare himself to a UFO. He keeps many of these words laced with expressions of thankfulness, an echo of his groundbreaking Tumblr post where he revealed that his first true love was a man and that getting his heart broken allowed him to grow as a person. He learns similar lessons in “Ivy” (“The feeling still deep-down is good”), “Pink + White” (“You showed me love, glory from above”), and “Self Control” (“I know you gotta leave, leave, leave”). He even brings a tiny dash of humor to the heartbreak in “Solo” by injecting wordplay into the title (“solo,” “so low,” like that) and masturbation double entendres into the verses.

As Blonde gets closer to the finish line, the same themes get explored again and again with a more collagelike musicality. The entire first half of side two (if the album ever actually does get sides) consists of sketches rather than traditional songs, most of them jumping from section to section in a brief runtime. There’s a reprise of “Solo” rapped at machine-gun pace by André 3000, followed by the discordant sound experiment of “Pretty Sweet,” the “Facebook Story” interlude, and a broken-up, hollowed-out cover of Burt Bacharach’s “(They Long To Be) Close To You” (simply titled “Close To You”).

The downside to this pastiched whirlwind is that, when coupled with the constant pining of the lyrics, Blonde’s back half largely becomes overkill. Maybe that’s the point—to keep ratcheting up the weight and frequency of heartbreak until the listener feels exhausted—but one can’t help but long for some new ideas after finishing “White Ferrari.” With its pixelated subversion of The Beatles’ “Here, There And Everywhere” followed by a gently strummed outro, it’s the emotional apex of the album, the natural conclusion to its romantic travails. But the well-wishes to the one (or ones) who got away continue—albeit in a busier, more segmented fashion—with both “Godspeed” and “Seigfried.” At this point, the music has become so moody, murky, and inward (there’s a reason guest stars like Kendrick Lamar and Beyoncé are relegated to walk-on roles), the story borders on obsession and solipsism. As if he’s aware of all the alienation and repetition, Ocean even tells listeners they could have changed the track on “Futura Free.”

Maybe it’s pointless to want a Frank Ocean album to be fun or at least stay warm until the very end. But when the same ideas keep getting recycled—even through his evocative lens of nature, nightlife, and nostalgia—the transcendence ends up giving way to numbness in the home stretch. Still, the guy deserves credit for achieving transcendence in the first place on most of Blonde, even if, like Endless, it could use an editor.