Breathe is the Theory Of Everything that 2017 never asked for

Certain movies are so pervasively influential that filmmakers citing them as an inspiration are immediately suspect. Who can really trust, for example, any new director who fancies himself (or herself, but come on: himself) the author of the next Reservoir Dogs, Harold And Maude, or Full Metal Jacket? But Andy Serkis, the talented actor specializing in motion capture creations, has found something far worse. His movie Breathe seems to want nothing more than to be The Theory Of Everything for a slightly newer generation.

This might sound reductive, comparing one sorta biopic of an English guy in a wheelchair to another sorta biopic of an English guy in a wheelchair. But it’s not superficially similar subject matter that makes Breathe so familiar, but rather its similarly bizarre approach to storytelling. Like its spiritual sibling, it skips through a long time line with a shocking lack of narrative momentum, purportedly building an inspirational story on the bedrock of a loving relationship while really just explaining that a guy who didn’t give up also had a wife. Both play like something several degrees removed from real movies, like outlines of pitches or schematics for a hypothetical awards movie (which Theory somehow actually became).

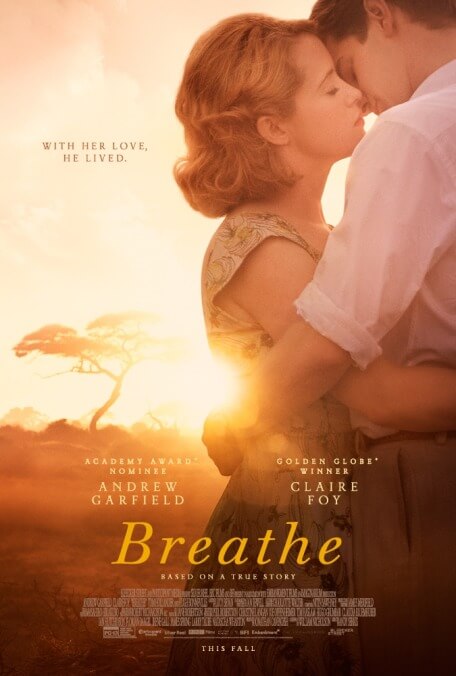

Breathe also plays a little like a prequel, because it’s about how Robin Cavendish (Andrew Garfield) was able to get into a wheelchair at all. Serkis whisks the movie through Robin’s 1950s courtship of Diana (Claire Foy); they meet during the opening credits, and before long the two are married and Diana is pregnant. They’re on a trip to Africa when Robin falls ill with polio and becomes paralyzed from the neck down, requiring a machine to keep him breathing. Doctors, who in this movie exist primarily to issue stodgy, doomsaying proclamations, estimate that he has just weeks to live. But Robin ignores his doctors’ stodgy, doomsaying insistence that he must stay in their facility to receive end-of-life treatment and moves home, with the support of Diana.

Robin also receives help from his close friends, including Teddy Hall (Hugh Bonneville) and his twin brothers-in-law David and Bloggs (both Tom Hollander). After an at-home mishap with his breathing machine, he gets to thinking about other options and eventually is able to leave the house on an elaborate wheelchair with a built-in breathing mechanism. Soon he takes longer trips. Later he gives a speech about it (to a roomful of stodgy, doomsaying doctors, naturally). This is about all there is to the movie.

Breathe’s producer would probably say that the story is about a triumph of the human spirit that helped revolutionize care for thousands of others like him. One reason he might say that is that he is Jonathan Cavendish, the real Robin Cavendish’s son. The younger Cavendish has crafted a nice-looking, warm-spirited tribute to his father, but he has not exactly made a movie. Garfield, who is no stranger to roiling with inner turmoil, spends a surprising amount of his screen time grinning merrily and facing obstacles with gentle good humor. He is a wonderful role model and a pretty boring character; the same goes for the fiercely loyal Diana. Garfield and Foy both give admirably unfussy performances—their emoting is restrained and occasionally touching, told more through gesture than histrionics. There just isn’t much to tell. Robin becomes more or less unflappable within about 30 minutes of screen time and stays that way to the would-be tearjerking end.

Breathe does have an ace in the form of cinematographer Robert Richardson; occasionally the film pauses to allow Richardson and Serkis to linger on particularly lovely compositions, like a pull-back from a slow-motion scene of Robin at home with his young son that has a painterly quality, or a silhouetted early slow dance between Robin and Diana that fairly glows with Old Hollywood romanticism. A whole movie of these moments would have been something special, or at least something less like The Theory Of Everything.