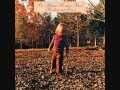

Brothers And Sisters found The Allman Brothers Band wandering into uncertain territory

Permanent Records is an ongoing closer look at the records that matter most.

In virtually any other band in the world, Dickey Betts would have been the alpha dog, a superlative guitarist with the creativity to push his bandmates to new heights. But Betts happened to be a founding member of The Allman Brothers Band, which already had its leaders, the mercurial Duane Allman and his brother Gregg. In the fallout from Duane’s death in a motorcycle crash, The Allman Brothers Band struggled to recenter its identity, and Betts sought to assert himself more, with mixed results.

If the band’s third studio album (not counting their seminal live At Fillmore East) Eat A Peach was an epic Southern wake for their dearly departed leader, then the follow-up record, Brothers And Sisters, finds the group in a more contemplative mood. Still mourning Duane’s absence, and with the additional hurt caused by bassist Berry Oakley’s death—in an eerie coincidence, again in a motorcycle crash—The Allman Brothers Band turned inward to search out new directions in which to take the band’s sound.

At the core of Brothers And Sisters lies a basic creative tension between the competing visions of Gregg Allman and Dickey Betts. Of course, the band’s sound had always been driven by difference, primarily the gap between the styles of Duane Allman and Betts. What makes the early Allman records special is the interplay between the two guitarists, who create complementary lines even while offering radically different sounds. Allman brings the fire, with his rough, playful bluesy sound, while Betts acts as the ice, his more methodical, technical style giving a slickness to even his trickiest licks.

Together they create a sound greater than the sum of its parts, pushing each other while maintaining a basic balance. This is equally true of songs where Duane takes the lead (as in “Whipping Post”) as it is of Betts’ own compositions, like the silky, jazzy “In Memory Of Elizabeth Reed.” On Eat A Peach, which features Duane on a few tracks that he recorded before his death, the difference in tone is apparent between the two halves of the record; the album-closing tracks “Blue Sky” (written by Betts) and “Little Martha” (written by Duane Allman) represent the harmonic interplay of the two guitarists at its best.

With Duane gone, the delicate equilibrium soon became skewed, and Brothers And Sisters manifests the fundamental imbalance left by Duane’s death. Though Gregg Allman had always been the group’s primary songwriter, Duane had been its soul, and absent his steadying presence the album wavers back and forth between the starkly different sensibilities of Gregg and Betts. For the first time Betts was able to stretch his wings as a songwriter, penning four of the album’s seven tracks. At the same time both he and Gregg struggled to imagine a sound for the band minus Duane. This makes Brothers And Sisters a less transcendent album than any of the band’s previous efforts, but it also turns the record into the group’s most historically fascinating work, a snapshot of a band caught mid-transformation, with no clear idea of the best path to follow. The results, though uneven, have their own magic.

It’s one of history’s little ironies that The Allman Brothers Band produced their biggest, most iconic hit after the death of their most important member. Then again, it’s easy to hear why “Ramblin’ Man” slides down a little easier than some of the band’s more challenging songs.

Taken on its own merits, “Ramblin’ Man” is a great song, and it shares a lot of DNA with other classic Allman songs. Yet scratch beneath the surface, and the song feels distinctly less memorable than tracks from the earlier records. Betts mimics the band’s dual lead guitar sound, subbing in session player Les Dudek for Duane, and while Dudek keeps pace admirably, the harmonies feel too rote, too locked into their pattern to go in adventurous directions.

That predetermination bleeds over into the lyrics and Betts’ vocal performance as well. There should be real pathos to Betts crooning lines about being born, fatherless, in the back of a Greyhound bus, but his dispassionate voice glides right over these details. The song has obvious predecessors in the Allman catalog, most notably “Midnight Rider” and “Melissa,” but while those songs elicit deep emotions thanks to Gregg Allman’s husky voice, “Ramblin’ Man” struggles to become more than a good tune smoothly played.

Or contrast it with the song that comes right before it on Brothers And Sisters, the Gregg Allman penned album opener “Wasted Words.”

Musically less interesting than “Ramblin’ Man,” and lyrically overstuffed, “Wasted Words” nonetheless makes great use of Allman’s crusty voice to lend gravitas to lines like “I ain’t no saint and you sure as hell ain’t no savior.” There’s a desperation on display that marks the song as springing from the blues side of the band’s lineage, but also a frustration that points to confusion.

Despite the gap between the two songs, both in style and mood, “Wasted Words” and “Ramblin’ Man” share an important connection: a preoccupation with rootlessness that winds its way through all of Brothers And Sisters. While Allman’s song wallows in the disorder brought on by disillusioned hope, Betts’ tune explores the more hopeful possibility that, in the midst of rambling, one might still stumble across life’s pleasures.

This dichotomy, between hopeful and anxious uncertainty, carries over into the other songs on the album. Allman’s only other composition on Brothers And Sisters, “Come And Go Blues,” aches with the same agony as “Wasted Words.”

Here the lyrics show a mind tormented by vacillation. “Oh, if only you would make up your mind / Take me where you go, you’re leaving me behind,” he pleads, as Chuck Leavell’s piano inserts a rhythmic urgency into the petition. Though addressed to a fickle lover, “Come And Go Blues” works equally well as a pained meditation on what the future holds. Brothers And Sisters catches the band on the cusp of great changes, but none of the members feel quite sure if the changes bode well for them or not. “Come And Go Blues” anchors the album in a sense of foreboding, as The Allman Brothers Band twists in the winds of fortune.

Betts, meanwhile, maintains at least an air of confidence in the face of uncertainty. Certainly a straightforward jam like “Southbound” points to his innate sense of direction: when cut adrift, you can always return home, to the South. But even when the destination is less sure, as in album closer “Pony Boy,” Betts keeps his chin up, alive to the playful possibilities of the future.

“Pony Boy” is one of the strangest songs ever recorded by The Allman Brothers Band, and it becomes especially odd in context—why close the album with such a wispy, seemingly slight song? The offbeat sound starts with the instrumentation, with Betts picking up a Dobro for the song, a resonator guitar that lends the tune a distinctly country twang. Of all the members of the band, Betts had always been the most indebted to country sound, but here he lets loose, with the twang affecting even his voice, which becomes a tad more gravelly than usual.

“Pony Boy” would not sound out of place at a square dance, and the song has an infectious energy about it, even as it remains low key throughout. Though the song advocates a party ethic, its lackadaisical attitude exists side by side with an uncertainty about the future. The dance all night moral of the song fits uneasily with the presence of the singer’s “Ole man” and the unstoppable creep of morning. The song ends upbeat, with Betts confident in his pony’s ability to guide him home safely, but the album gradually fades into silence, suggesting a future that could go either way.

Brothers And Sisters lurches back and forth between confidence and anxiety, with the two moods mostly failing to mingle. The album thus feels like two halves of the band’s character are being pushed centrifugally apart from each other, a sort of foreshadowing of the breakup that would strike a few years later. On one song, however, the center seems to hold. Appropriately, the song is the album’s only instrumental number, “Jessica.” Though the band’s lyrics occasionally approach elegance, the poetry of The Allman Brothers Band resides primarily in the music itself, and “Jessica” finds the band temporarily reconciling through a shared, cohesive sound.

On the whole the song has the relaxed vibe associated with Betts, who wrote it. Carried along by a guitar lick as smooth as butter (aided again by Dudek, now on acoustic guitar, whose sound blends more comfortably here than on “Ramblin’ Man”), the song ambles from high point to high point, affording plenty of solo opportunities for the band members, with Chuck Leavell’s piano once more a highlight. In seven fleet minutes the song channels the band’s most freeform, virtuoso live performances, and The Allman Brothers Band feels Duane’s absence a little less.

What makes “Jessica” successful, though, is the urgency which pokes its head through the calm surface. If Betts tends to sacrifice emotional depth to technical proficiency, “Jessica” curbs this habit. Betts’ guitar still sails along the surface of the song, but the full sound of the rest of the band reveals a depth underneath. Gregg Allman’s organ playing—usually less distinctive than his vocals, but here a powerful part of the equation—pulses in the background, reminding the listener of the turmoil below. The band’s great dual drummers, Butch Trucks and Jaimoe, pound away at various percussion instruments, including congas. And Lamar Williams, brought in to replace Berry Oakley on bass, lays down a solid foundation. In spite of all the tension and grief, for a few brief minutes in “Jessica,” the band transcends its own troubles to recapture its old sound.

Such harmony would not last, sadly. The Allman Brothers Band had a few more albums in them before breaking up (then reforming, then breaking up again and reforming off and on, up to 2014 when the band finally called it quits for good), but Brothers And Sisters, as wavering as it can be, represents the last gasp of greatness of the group as originally formed. Lurching from mood to mood, never settling into its own skin, Brothers And Sisters contains the raw talent and rough edges of a great band set adrift by tragedy.