Bruce Dern traces his career progression from “fifth cowboy from the right” to American icon

Welcome to Random Roles, wherein we talk to actors about the characters who defined their careers. The catch: They don’t know beforehand what roles we’ll ask them to talk about.

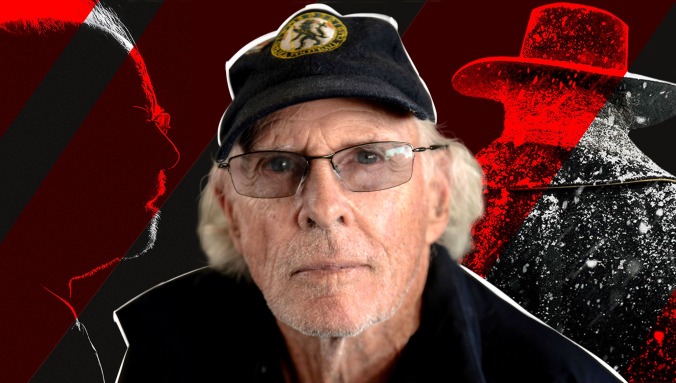

The actor: At 81, Bruce Dern belongs to a generation of actors that’s slowly fading away. He learned his craft from masters like Elia Kazan and Lee Strasberg, honing his chops on the stage alongside Paul Newman and Geraldine Page in Sweet Bird Of Youth. Dern did his time on TV by appearing on such iconic series as Gunsmoke and Wagon Train, but it was on the big screen where he truly made his mark, earning infamy for killing John Wayne in The Cowboys, winning praise from Alfred Hitchcock for his work in the director’s final film, Family Plot, and scoring his first Oscar nod in 1979 for his performance in Coming Home.

It would be nearly 35 years before the Academy Of Motion Picture Arts And Sciences favored Dern with another nomination, and while he didn’t take home the glory for 2013’s Nebraska, he received some of the best reviews of his career. Since then, Dern has continued to do the same thing he’s done throughout his 60-year career—work steadily—and has several new films forthcoming, but this week he can be found on HDNET Movies hosting Bruce Dern’s Cowboy Collection, which consists of 15 Westerns, including one of his own: Posse.

Posse (1973)—“Jack Strawhorn”

Bruce Dern: That was very interesting. Kirk Douglas was the director and starred in it with me, and he was very kind to me and very generous. It was a very good script. Unusual. And I think he’d only directed one movie before that, called Scalawag or something like that. It was good. The political side of it was hidden extremely well, but it was a guy who thought he was presidential material… and then he turned out to be more crooked than the crook!

AVC: One might argue that there could be some relevancy in today’s political climate.

BD: Oh, absolutely. In fact, when we were doing the movie, Kirk was a very dear friend of Henry Kissinger’s and Pierre Salinger’s. He went to see Kissinger in Washington, and when they went to the White House. Kirk was very impressed by the power he felt when he sat at the president’s desk. [Laughs.]

Wild River (1960)—“Jack Roper”

AVC: One of the other movies that’s part of the marathon is Pat Garrett And Billy The Kid, which…

BD: I’m not in that.

AVC: That’s what I was going to ask, since IMDB has you listed as “uncredited” in the film. So you’re not in it at all, then.

BD: No, but it’s been listed in my credits for a long time. I don’t know why. I’m not in it!

AVC: On the other hand, you also aren’t listed in Wild River, but you are actually in that one.

BD: Yeah, that was my first film. I was under contract to Mr. [Elia] Kazan. He had five of us: he had Rip Torn, Pat Hingle, Geraldine Page, Lee Remick, and me. I was kind of the baby of the group, I think, and Wild River… I was doing Sweet Bird Of Youth on Broadway, which was a Tennessee Williams play that starred Paul Newman and Geraldine Page, and Kazan directed it. And Gadge [Kazan’s nickname] asked me if would go down and do this movie, and he took me out of the play and I went and did that. That was interesting because, first of all, Montgomery Clift, Lee Remick, and Jo Van Fleet were the three stars of it, and Jo Van Fleet played a 92-year-old woman. Just four years earlier, she played a 60-year-old woman, and both movies were done when she was in her thirties! Because when she played this 60-year-old woman, she was 35, Jimmy Dean was 25, and she played his mother. That was in East Of Eden. Four years later, she’s added another 32 years. She was a fabulous, fabulous actress.

It was my first movie, and… I was guilty of probably one or two “Dernsies”—just little injections of dialogue or behavior that aren’t on the page—before Jack Nicholson ever named my little things that. But Kazan… I was with Mr. [Lee] Strasberg for nearly two and a half years, and then they said, “You can go to Hollywood now,” so when I went, Kazan said to me, “Now look, you’re going to go out there, and no one’s going to know who you are or appreciate you until you’re in your 60s.” And I said, “Jesus Christ, Gadge!” [Laughs.]

He said, “Look, you’re going to go out and be the the fifth cowboy from the right, okay? Get that through your head, because you are not a movie star. You have no individual identity, because you always seem to become the roles you play. So you’re not an obvious leading-man movie star. So you’ve got to accept that. But you will get your day when you’re older and they start realizing that you have the dexterity that you have.”

I said [Sarcastically.] “Well, that’s just fabulous news. Thank you for telling me that.” And he grabbed my shirt lapel, and he said, “You just make sure you’re the most unique, interesting goddamned fifth cowboy from the right anybody ever saw.” Which meant that I had a right to do a Dernsie now and then, because they’re never self-aggrandizing, they’re just to increase an audience’s level of who the character is, because he’s only got five lines! [Laughs.] So I said, “And how do I get away with that?” He said, “Don’t ever tell a director what you’re going to do before the first shot.” And I said, “How the hell will I get away with that?” And he said, “Because he has something that you will never, ever have.” I said, “What’s that?” He said, “Take two.”

Castle Keep (1969)—“Lt. Billy Byron Bix”

They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? (1969)—“James”

BD: I did a wonderful movie—I had real trouble even getting a copy of it—called They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? That was a terrific experience. I’d just done a movie in Yugoslavia for Sydney Pollack called Castle Keep with a bunch of us. Burt Lancaster was the star, but it was Tony Bill, Michael Conrad, Peter Falk, and Patrick O’Neal, and Scott Wilson. It was a group of guys who would go on in their careers, but early on Sydney Pollack kind of picked me out for it, and I appreciated that. And just a year later we were shooting They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?

That was a wonderful experience because every day we had music on the set. It’s about dance marathons, and every day they were playing songs. They had a pianist who was there, just like they did in the real dance marathons, and the songs were being played and sung by Johnny Greene, the guy who wrote them.

AVC: It’s amazing to think that Bonnie Bedelia was all of 18 when she did that movie.

BD: Yeah, she was! And I had to take her to her biology class once a week at Hollywood High School. She and I were partners in the film. We end up winning the contest. But it’s not a big deal, because Jane [Fonda] is out on the end of the pier, begging Michael Sarrazin to take her life! I thought that movie kind of captured an era. If it had been made now, I don’t know what would’ve happened to it. It was certainly ahead of its time. And Gig Young won an Academy Award for it!

Smile (1975)—“Big Bob”

BD: Smile’s one of my favorite films. I liked it because it was full of guilty innocence. It’s really a black look at American beauty contests, but it was very funny, very genuine, and a guy named Jerry Belson wrote it. He’s gone now. And Michael Ritchie, who’s also gone now, he directed him. I did some other movies for Michael Ritchie. I did a movie called Diggstown. The way I met him, though, was that I did a bunch of Big Valley episodes, and he directed Big Valley when he first came out from Harvard. He had a funny career. He was really successful early on. He was also 6-foot-8, so he was a big, tall guy. I remember standing in a room with him and Michael Crichton, and they’re both enormous. Crichton was just huge! I got a kick out of that, because I did a movie called Silent Running, and Douglas Trumbull was a good friend of Michael Crichton’s. But Smile was good, I thought.

We made it in 1974, and I made Posse right after that, within three months after that. But what I really liked the most about Smile was that it worked. You know what I mean? It just worked. And they did a great thing with the script. At the end, when they sent the script out to us, they didn’t tell you who won at the end. So throughout the whole shooting of the movie, they never let anyone know who was going to win. And they didn’t know! And after we went through the progress, the last afternoon, before we shot that final night, they decided the girl who would win. And none of the girls knew. So all of those girls who won the prizes, that wasn’t scripted at all. You got real surprise.

And the other thing they did that was really cool… They needed to fill that auditorium in Santa Rosa, and the only way that they could fill it was to get about 2,000 people from Santa Rosa to come and shoot and be in a movie for four days. So they charged them to be extras! [Laughs.] They charged each one $25 for four days. And they were paid. But they charged them first. And at the end of each one of the four days, they’d give away cars from Santa Rosa car dealerships. So that’s the way they kept them there after lunch: They’d give them a token each day, and that was the way they kept them there after lunch. Otherwise, the people would’ve bailed out at lunchtime.

The ’Burbs (1989)—“Mark Rumsfield”

BD: I liked The ’Burbs. I love Joe Dante. When I got my star on Hollywood Boulevard, Joe Dante’s the guy that introduced me. My family—Diane Ladd, my daughter Laura, and myself—all got stars at the same ceremony. Joe Dante introduced me, Della Reese introduced Miss Diane, and David Lynch introduced Laura. You know, Joe Dante… At the beginning of his career, he was a movie critic for the Philadelphia Bulletin, which was the evening paper in Philadelphia. That was in 1972. And then when he came to Hollywood, [Steven] Spielberg kind of took him under his wing, and he made those movies like Piranha and The Howling, and then he made Explorers and a lot of movies about children in jeopardy. The ’Burbs was one of those, and I liked it. Movies shouldn’t be a grim dance. They should be fun! And that was a lot of fun.

I got a chance to meet and work with Carrie Fisher. Tom [Hanks] I didn’t know before then. Tom was an actor on the verge. As a matter of fact, I remember one day I was off and I went to see Big, because it’d just opened that day. Afterwards, I called him. In fact, I called him off the set! And when he came to the phone, I said, “I just want to tell you: I just saw Big, and you are going to be a huge movie star.” And he said, “Really? Why do you say that?” I said, “Because you’re funny and you’re likable, and audiences will embrace you no matter what you do.” And luckily I was right. The only big credit he had before that was Bosom Buddies, the TV show.

AVC: The ’Burbs also introduced many people to Brother Theodore.

BD: Well, absolutely! I didn’t know who he was. I didn’t know he was a [Greenwich] Village legend or any of that. But, yeah, it had Brother Theodore, it had Henry Gibson, it had Courtney Gains, who’d done nothing except Children Of The Corn, and Corey Feldman, who—of all the movies I’ve been in —has the most appropriate last line of any of them. When he runs out after all of the mayhem, he says, “God, I love this street!” [Laughs.] And Joe Dante, he just has fun all the time making films. He hasn’t had quite the career I think he’s wanted, but he’s done very well.

Diggstown (1992)—“John Gillon”

BD: I had just done a TV movie with Lou Gossett in Atlanta [Carolina Skeletons], and he said, “You know, I’m doing a movie, and there’d be a great part in there for you.” And he suggested me, and Michael Ritchie, I guess, said, “Oh, my God, I forgot about Bruce Dern. Yeah, let’s put him in there!” And it kind of worked. All the boxing guys… We each got to pick five men to box, and one of the ones that he picked was Jim Caviezel. That was his first movie. And then I did a movie with him a few years later called Madison, which was about powerboat racing on the rivers in America. But Diggstown, that was a lot of fun.

Lou Gossett, I’ve known him ever since he began. He was a huge success on Broadway when he was 9 years old, because he was in a play called Take A Giant Step. That kind of made his career as a good young actor. And Jimmy Woods, I always respected him a great deal as an actor. He had tremendous range, and he was very believable. That was a key thing to me. There were a lot of actors who didn’t have the ability to look you in the eye, and he was one who did it very, very well. But I saw about a month ago that he wasn’t going to do it anymore and that he’d retired. It’s too bad, because he was really good.

AVC: I think he’s backpedaled on that a little.

BD: Oh, he has? Maybe he’s just slowing down. It sounds like he’s a little bit like Jack [Nicholson], in his own way: unless he can get a script that beats anything he’s done, I don’t see him wanting to do it again, but he’s always available.

Drive, He Said (1971)—“Coach Bullion”

BD: Speaking of Jack, there’s three things that really bother me that’ve happened to me over my 60 years in the industry. The first thing is that they never gave Roger Corman more than a million dollars to make a movie. The second thing is that Jack Nicholson was never really allowed to direct again unless he appeared in the movie. Because he directed me in Drive, He Said, and he wasn’t in Drive, He Said. But he was a fabulous, fabulous director.

And the third thing is, I had a good friend, Michael Cimino, and I always regretted the way the industry treated him after Heaven’s Gate. I didn’t think that was really fair. I mean, he went over budget—it was $30 million, ultimately, and you could do 10 CSIs for that—but he was a master at “once upon a time” yet could make it seem very, very relevant. Yes, Heaven’s Gate is too long, but it’s got some brilliant moviemaking in it. Also, people don’t remember, but he co-wrote Silent Running.

Silent Running (1972)—“Freeman Lowell”

AVC: You don’t really have a lot of sci-fi in your back catalog.

BD: No, as a matter of fact, I’ve tried to make it a point of never being in a movie that couldn’t really happen. In other words, I’m not good in a movie where you run up the wall and stab somebody with a 27-inch sword or some shit like that. Silent Running, I think, was the only one that was like that. I would’ve liked to work for Ridley Scott, if he would’ve ever had me. I think he goes into that area very, very well. There’s always a sense of believability in what he does, and I like that. I’ve just never been offered anything that took me into that area.

But in Silent Running… Do you know what the little drones were in real life? They’re people, all of whom were cut off at the waist. So they are walking on their hands, because they have nothing from the bellybutton down. One was a thalidomide child, and the other three were—it’s horrible to say—cut in half by accidents. So that was kind of amazing. It’s what gave the drones the adorable little quality of waddling around. They’re not waddling, they’re walking on their hands! Pretty ingenious. And that’s two years before R2-D2!

World Gone Wild (1987)—“Ethan”

AVC: There’s just one other sci-fi film in your catalog.

BD: Oh, yeah. [Laughs.] Well, a couple of things about World Gone Wild. First of all, I thought Michael Paré, who was in the movie with me, who had just done Streets Of Fire, was gonna be one of the big movie stars from his generation. He was a good actor, he was extremely funny, and he was a very good-looking guy. He didn’t seem to have any problems that would keep him from pursuing a career. I thought he would go a long way.

And the girl… Catherine Mary Stewart! She’s another one: I thought she might’ve had the career Mary Stuart Masterson ended up having. Three names, also. Or Jennifer Jason Leigh, if you will! [Laughs.] But she was very good. The director was a guy who’d been an assistant director on several shows I’d been on, a guy named Lee Katzin. That movie was a lot of fun, too. And do you remember who my other co-star was?

AVC: I do, because that’s what really caught my eye: Adam Ant.

BD: Right, absolutely! And he was delightful. I mean, really delightful. And he seemed to have a cadre of young, good-looking girls around him, because he was a big star, musically. Adam And The Ants!

The Cowboys (1972)—“Long Hair”

BD: One of the neat things about my career has been the people I’ve gotten to work with. My generation was extremely lucky, because when we came to Hollywood, we still had a chance to work with the legends. We’re not legends today. You can’t be a legend today. Everybody knows what you do after school. There’s no secrecy after school. But what people forget is that—regardless of acting ability—those people were bigger than life, and that’s because we didn’t know anything about them except the characters they were playing.

I was lucky enough to work with John Wayne a couple of times, Kirk Douglas a couple of times, Robert Mitchum, Bette Davis, Olivia De Havilland… Just a whole bunch of ’em. And I found—and I think Nicholson found the same thing—that everyone encouraged me again and again to push the envelope and go out on the edge. I liked that.

I remember the day I shot John Wayne in The Cowboys. He had never had a bullet hit put on him. Never! And he leaned into me and said [Doing a John Wayne impression.] “Is this gonna hurt?” And I said, “Absolutely it’s gonna hurt! You should get one of those big USC Marching Band Roman shields that you put on the front of you, ’cause they’re gonna blow a hole in your chest!” And he knew that, but he’d never had it done. Mark Rydell was the director, and we decided that the only way the scene could really work for an audience is if Wayne was surprised. So unbeknownst to him, we put a bullet hit in the back of his jacket. And I shot him in the back the first shot. And he did not know that was gonna happen. He played it like a pro, went all the way through it and everything, got up, and told Mark Rydell and I we were both pricks. [Laughs.]

Oh, and just before we did the shot, he said, “Oh, they’re gonna hate you for this.” I said, “Maybe. But in Berkeley, I’m a fucking hero!” He got a big kick out of it, because he’d just done the Playboy interview. They did a big, long interview with him where he kind of ripped America a new butthole unless they lived on Balboa Island, where he and the rest of the boat people lived.

But [John Wayne] was just great to me. He did something to me that was the most welcoming, inviting thing in my career. He said to me on the first day, “I want you to do me a favor.” I said, “Yessir?” He said, “I want you to pick on me all day, every day, and be absolutely careless with your attitude toward me, so that these little kids that are scared shitless of me, if you can treat me like that, then what might you do to them?” And it worked! And had he not given me that blessing, so to speak, I’d have backed off a lot. But I didn’t.

Gunsmoke (1966)—“Lou Stone”

BD: Mitchum was that way, too, and Bette Davis was certainly that way. I said in my book, the only time I ever had tears in my eyes on a set, other than in a scene, was when I went to work one day on a Gunsmoke. The first AD was Walter Hill, and he came up to me and said, “Wait ’til you see who’s playing your mother today.” And it was Bette Davis. And I got tears in my eyes. And she said, “Bruce Dern! You come over here right now! What’s the matter with you?” I said, “Bette, it’s a Gunsmoke.” And she said, “Well, at least it pays for my cigarettes. I just took out an ad in the trades that said, ‘Seven-time Oscar nominee looking for work.’ And I got a Gunsmoke!” She was a class act.

In my book [Things I’ve Said, But Probably Shouldn’t Have: An Unrepentant Memoir], I talk about other women, and of course Geraldine Page was fabulous, but Lee Remick was probably the most saint-like woman I ever worked with. And this February, because my daughter Laura was the head of the acting branch of the Academy, she had a little dinner party, and she invited six of us who’d won Oscars more than once, and then six nominees from this year. So there were 12 of us. It was myself, Laura, Richard Dreyfuss, Tom Hanks, Michael Fassbender… But this’ll knock you out: a 95-year-old woman sat next to me and my assistant Lisa during the whole time, and she was as sharp as a tack and still beautiful. That was Eva Marie Saint. When you think of it, she’s 95, Olivia De Havilland is 101, and a year and a half ago, I did a movie with Cloris Leachman, and she’s 91! So these dames are really durable. [Laughs.] I’ve really got to hand it to them! Eva Marie Saint doesn’t work, but I don’t think people think to ask her. I think she probably would. But Cloris’ll work. She’d work a state fair if you’d let her!

Marnie (1964)—“Sailor”

The Alfred Hitchcock Hour (1964)—“Jesse,” “Roy Bullock”

Family Plot (1976)—“George Lumley”

BD: I sat right next to Hitchcock for 10 weeks on Family Plot—I didn’t want to miss anything—and he let me. He said, “Sit down, Bruce.” And he told Time magazine a great thing about me. He said, “If indeed I ever did say that actors were cattle, then Bruce is the golden calf.” I got a kick out of that. And he always used to tell people I was the Humphrey Bogart of my generation.

When I worked with Hitchcock, he did the most amazing thing I’ve ever seen done in my life, and when I told Quentin [Tarantino] this and I told Alexander Payne this, they freaked out. At the end of the first day of shooting on Family Plot… He always sat in a little director’s chair. But it’s the end of the day, and Howard [Kazanjian], the first AD said, “Okay, that’s a wrap,” and Mr. Hitchcock said [Does a Hitchcock impression.] “Howard, I’d like to have a word with the crew.” Howard said, “Of course!” And then he got up… and when he got up, the chair went with him, because his sides stuck through the holes where his arms were on the armrests. And he never even turned to me: he just said, “Bruce! A hand, please.” So I stood up, grabbed the legs of the chair, which were parallel to the ground, and he walked out of it. He walked to the edge of the stage we were using, and he said, “Ladies and gentlemen, I’d like to thank you for quite a wonderful first day.” And they all kind of gave him a nice little hand of applause and started heading for the exits. And he said, “No.” And he cupped his hands, and he said, “Personally!” And they all stopped. This was 1975. But he walked around the set—no bullshit—and thanked 77 crew members by their first name.

AVC: That’s remarkable.

BD: Yeah, Alexander and Quentin, they both have a bunch of people who work for them, but not nearly like Hitchcock did. In fact, they have many more. Hitch had about 28. But the rest, he just learned their names in one day. And I’m talking even the guys up on the flywheels, 40 feet in the air. All of ’em.

I’ll tell you a cute story. When we were doing Family Plot, Steven Spielberg used to come on our set at Universal and kind of hover in the back, watching. And one day Hitch turned to me and said, “Bruce! What’s that boy hovering in the back for? What’s he doing here? He’s here at least two or three days a week!” I said, “Well, that’s Steven Spielberg, and he just wants two minutes to tell you how fabulous an impression you have made on him and the way he makes films.” He said, “Is that the boy that made the fish movie?” And I said, “Yes, that’s Steven Spielberg.” He said, “Oh, no!” And his hands started shaking. And he looked at me and said, “Never! Never! I don’t want him near me! He makes me feel like such a whore!” I said, “What are you talking about?” He said, “Two months ago, Lew [Wasserman] called me up and asked me if I’d like to make two million dollars in 20 minutes. I may be British, but I’m not a fool, so I did it.” I said, “Yes?” And he said, “Bruce! I was the voice for the Jaws ride!” When they opened the theme park that year, they had a Jaws ride, and Hitch’s was the voice that said, “Come! Take the Jaws ride!” Every time Steven hears the story, he gets goose bumps. But he never did meet with Mr. Hitchcock!

AVC: Just to jump back to your first time working on a Hitchcock film, how was the experience of working on Marnie?

BD: I’ve now kind of come full circle with Marnie. I’ve worked with Tippi [Hedren], I’ve worked with Melanie [Griffith, Hedren’s daughter] on Smile, and I just worked with Dakota [Johnson, Griffith’s daughter] on a movie called Peanut Butter Falcon, which we shot down in Savannah. So I worked with all three of them! And Tippi… I never really had a scene with Tippi in the movie, because I’m a flashback. Louise Latham played my girlfriend, and she had brought me home for the evening, if you will, and she had a little girl. And it started to rain real hard, and I got up off the couch or wherever I was and walked over to start to comfort the little girl. I wasn’t doing anything to her, but she thought maybe I was, because I was a sailor, wearing my white uniform, and I guess sailors are supposed to be troublemakers, I don’t know. Anyway, they beat me to death with a fire poker. [Laughs.] And I bleed all over my white uniform, so whenever Marnie gets upset when she sees red on white, it’s from that incident.

I remember that Mr. Hitchcock was shooting other scenes on another set that day, because we were on a special set with special lighting, and a big bulb for a camera that was made by Hasselblad that cost them $37,000 a day to use. What it did was distort a little bit everything in the foreground, and everything in the background was crystal clear and sharp. It looked like a huge light bulb in the camera.

So that was my first time working on a film for Mr. Hitchcock, but I also did a couple of Alfred Hitchcock Presents. The first one was before Marnie, and the next one was after Marnie, but he would always come down on the set when I was on there and say hello and greet me. People forget that Mr. Hitchcock directed a number of episodes. But Syd Pollack, Brian Hutton, and a lot of directors of that age group were under contract at Universal, so they were directing episodes as well, and they were all pissed off at Hitchcock because he made Psycho on the backlot in 18 days for $680,000. Lew would say, “Well, come on, what do you guys need a million dollars to shoot an episode of a TV show for? Look what Hitch did!” [Laughs.] So they had to kind of live by that rule.

Nebraska (2013)—“Woody Grant”

BD: I always say that I feel like I’ve worked for six geniuses in my career. Four directing genius and two producing geniuses. And the six directors, not in any order, would be Mr. Kazan, Mr. Hitchcock, Douglas Trumbull, Alexander Payne, Quentin Tarantino, and Francis Coppola. And everybody always says, “Well, why just those six?” And I say, “Well, those are six I worked with.” And they say, “Where’s Frankenheimer? Where’s Hal Ashby? Where’s Michael Ritchie? Where are the other people you’ve worked for?” Well, first of all, all of them have tremendous reverence for what went before them as directors, down to every single camera or unique effect. Secondly, there’s not a member of the crew—anybody, even the guy who cleans the honey wagon—who can’t approach any one of those men and ask them, “Sir, what is my specific job in this shot?” And they’ll tell you. That’s how thorough they are. And that’s what I call a genius.

Doing Nebraska with Alexander… That was a 10-year marathon for me. I’ve always said that the key to the business—the movie business, certainly, and I’m sure any other part of show business—is endurance. And I first got the script for Nebraska in January of 2004. I remember Alexander sent it to me, I read it, and I delivered a little red pickup truck to his office about two days later, along with a little note saying, “I am Woody Grant.” He never replied, except that my agent said, “Alexander was very flattered that you left something for him.” I said, “Well, that’s nice.” But then he wandered off and made Sideways! He couldn’t get Nebraska made. And then in 2010 he went off and made The Descendants! And I figured, “Well, fuck, this movie’s never gonna get made.”

And the reason he had such a problem… I like to think he never told me, but it was probably because he insisted on me being in the movie. He said, “I will not make the movie unless he’s in the movie.” And I knew that at the time. But oddly enough, Alexander—because of the pressure at Paramount—had to meet with every guy who could play the role in the studio’s mind, which he did. I wasn’t aware of who they were, but I was aware that there was a process going on that wasn’t about me, so I was scared to death that I’d never get a call about it again. The other thing was that Paramount and two other studios said they would never, ever make it in black and white. They said, “No way.” They offered him $25 million if he would do it in color with Gene Hackman. And he said, “Gene Hackman is not going to play the role. I’m sure he could play it, but there’s only one guy who can be an asshole and, at the same time, at the end of the film you want to put your arms around him. And that’s Bruce Dern. And that’s why I want him in this movie.” And they said, “All right, make your movie. You can make it in black and white. But make it for $9 million instead of $25 million.” So we went off and made it.

But Alexander said the most wonderful thing I’ve ever had said to me in my career on a set. It was at about 7:45 on our first day in a little, tiny town in Nebraska, and he said, “Do you see anything on the set this morning that you’ve never seen on the first day of a movie before?” I said, “Yes, I do. It looks as though everybody’s pulling their oar.” And he’s a very bright kid, an academic kid. He said, “Well, hopefully. That’s because we have 90 crew members here, and 70 have worked every day on every film I’ve ever made. So you, sir, can dare to risk. Because we’ve got your back.”

And then he said, “This is Phedon Papamichael,” who I’d met the day before, “and he’s your cameraman. I wonder if you’d do something for Phedon and I that I’m not sure you’ve ever done before in your career.” I said, “What’s that?” He said, “Let us do our jobs. Never, ever show us anything. Let us find it.”

I’d never met Al Pacino, but when he saw Nebraska, he saw me at an event and he gave me the greatest compliment I’ve ever had. He just said, “How did you do that? I never saw the work!” And I told him what Alexander said. And he said, “I don’t think I’ve ever had anything that specifically right-on said to me.” Because what he’s saying is, “You don’t need to act. Just be the character.” And of course it’s still acting, but don’t telegraph anything. Don’t show anything. Don’t underline anything. Just be there. I think he does that with all of his films, but with that movie, to hear that… Anyway, Al was very taken by it, and the next time he ran into Alexander, he spent some time talking to him about how he’d worked with me and so forth and so on.

Outside of George Clooney, I don’t know that Alexander’s ever worked with a major movie star at the height of their stardom. He’s only made six movies. His first starred my daughter, Laura. It was called Citizen Ruth. His second was called Election, with Reese Witherspoon. His third was called About Schmidt, with Jack and Kathy Bates. His fourth was Sideways, about the guys in wine country. His fifth was The Descendants, with Clooney, and the sixth was Nebraska. Now I guess he’s got Downsizing opening, and that’ll be his seventh. For now, though, I think he’s six for six!

Django Unchained (2012)—“Old Man Carrucan”

The Hateful Eight (2015)—“General Sandy Smithers”

BD: I’ll tell you about Quentin, who’s on equal ground. I’d never met Quentin, but he called me up and asked me if I’d come into his office when he was making Django, and he apologized to me because he didn’t have anything in the film for me. He just wanted to meet me and tell me how much I meant to him when he was growing up, watching me be an asshole on television. [Laughs.] And I was very flattered by that. About two months later, he called me, and he said, “I wrote a part for you. Would you do it?” I said, “I don’t know, I don’t want to be away from home on a movie like that. I’m sure it’ll take forever.” He said, “No, we can do it in an afternoon.”

It was a little part that hadn’t originally been in the script—he just wrote it for me—but it’s where Django’s chained against the wall and everything and I’m in the wheelchair, I’m a Southern plantation owner, and he’s my slave. And he tries to run off on me, so I let him know that I’m going to put him in the auction tomorrow, along with his wife, and we’re going to carve a little “R” into their faces so everyone knows that they ran off on me, so they’re likely to run off on anyone. And I told him that they had a lot of sand, and I said, “I got no use for a nigger with sand,” because they breed revolution. And the backstory is that he grew up in my family’s home because his mother was our family cook, but she died in childbirth, so he got to grow up in the big house, and that’s where he got a lot of his manners and stuff.

Anyway, that was that, but… [Hesitates.] He gave me a great line, and it’s in his cut. I don’t know where you see his cut, but Mr. Weinstein, in all his days of overly great—and by “great,” I mean just abundantly—hands-on films, Quentin did not have a final cut on Django. And Harvey Weinstein took out a line that was not a Dernsie. Everybody thought it was, but it wasn’t. Quentin wrote the line. But at the very end of the scene, I say, “And so we’re gonna sell her for the most money ever gotten at an auction for a slave and you for the cheapest amount of money.” And then my butler turns my wheelchair around, and I turn back and I look at him, and I say, “And if you think today’s gone bad for you, son, just wait ’til you start living the life of a four-dollar nigger.”

I’m surprised at Harvey. Quentin wanted it in, and like I said, it’s in his director’s cut. But Harvey nixed it and just simply said, “Not on my watch.” Well, excuse me, Mr. Weinstein, but let’s talk about facts. [Laughs.] I mean, the things he’s said in his other films are on record. I mean, Jesus Christ…

Every day on The Hateful Eight, I would go up to Quentin at the beginning of each day, and because he loved playing trivia with me, I’d say, “Okay, give me three Guy Stockwell movies!” And he’d say, “Beau Geste!” And whatever else. But it was always, “Bing! Bing! Bing!” I never stumped him. Never. And I was throwing out names of guys like Robert Viharo and Max Julien. Oh, but he got tears in his eyes when I mentioned Max Julien, because he loved Max Julien.

The thing I like best about Quentin, and I gave him this compliment more than once… We were at Comic-Con, and they asked all of us on this panel a question. It was all eight of us [from The Hateful Eight] and Quentin. And they got to me, and they said, “What about you, Mr. Dern? What do you think about all this?” And I said, “Well, let me say this: Quentin Tarantino has the greatest attention to detail on the set as a director of anybody that’s ever lived, except maybe Luchino Visconti.” And that’s a fact. Burt Lancaster told me once that Visconti was the greatest director he ever worked for, and I guess that’s because of The Leopard, which is a pretty goddamned good movie. The detail in it is unbelievable. And that’s Quentin. He’s the same way. And it’s not that Alexander doesn’t do stuff like that. He does. But his mind is in another area of what can make it better. The other thing I like about both Quentin and Alexander is that neither of them is sitting a quarter of a mile away from you at a monitor. They’re sitting right in front of you, directing.

Twixt (2011)—“Sheriff Bobby LaGrange”

BD: I understand Francis [Ford Coppola]. I did a movie with Francis that was barely released. It was called Twixt, and it starred Val Kilmer, myself, and Elle Fanning. Don Novello was in it, too. We shot it in Francis’ yard! [Laughs.] We shot it up in Marin at his estate. We had two days up in Clear Lake, but otherwise we shot it right there. Francis wrote it, and it’s a wonderful idea.

Val Kilmer is a broken-down Stephen King-type author, and he’s trying to write his new book while he’s on a book tour for his latest book. He’s come to my town, where I’m the sheriff, and he’s just closing up the signing at 2:30 in the afternoon, and this is after a 2:15 start, because he only had one lady who had asked to have her book signed. And I go up to him, and I say, “I would like to have you sign my book.” And he said, “Really?” I said, “Yeah, I would. I’m the sheriff, but I’m really interested in murder, and I write murder mysteries myself.” “Really?” “As a matter of fact, I’ve got a real doozy in the back of my office right now, because the coroner only comes once a week, and it’s three days ’til he comes again.” So I take him back, and on the slab, waiting for the coroner, is a dead girl laying on her back with a five-foot stake driven through her heart, and the top of it is a cross. And he wants to become involved with solving this murder. I said, “I don’t have a clue, but there are some bad people across the lake. The Goths. There are just freaks of Gothism all over the place.”

Well, since he’s writing his book on his tour, he starts writing his new book about this murder and how he’s trying to solve it with the sheriff. And when he can’t think of what to do with his writing, he goes for long walks in the woods, and when he’s in the woods, he runs into Edgar Allan Poe, who’s played by a kid named Ben Chaplin. And he complains to Poe that he just can’t get beyond this certain place in the book, and Poe tells him, “Well, first of all, you can never start a book without your end.” And he says, “Well, that’s what I don’t have! I don’t have an ending! I can’t solve the murder yet!” It was a really neat movie, and he took it to Comic-Con. And they really seemed to like it, but they were puzzled.

Anyway, so he had many chances to release it, but he makes very hard terms, and the business finally sunk it. And maybe he did it on purpose, but he showed us how it would work, me and Val. What he wanted to do was play it in select theaters, a city at a time, and he wasn’t looking to make money off it. He’d like to get his budget back, but his budget was $900,000 or something like that. We all worked for scale. So that was the end of working for scale for me!

He said, “What I want to do is, I want all the music in the movie to be played live on the theater organ, so I need the old movie houses. Each town will have an organist, and I’ll have the score up there for them, and they can play it throughout the movie. Well, the distributor said, “No one will ever buy that.” But a couple of people jumped immediately to buy it that way! One was in Buffalo, and… I don’t remember where the hell the other one was. But that’s what he wanted to use, so he never got a bid on it to make it worth his while to publicize it and send it out. So he didn’t do it. He’s a piece of work, Francis. I was sorry it didn’t come out [in theaters]. Elle Fanning, it was early in her career, I think she was only 16. And Val was very good in it.

Kraft Suspense Theater: The Hunt (1963)—“Maynard”

AVC: This is kind of an obscurity, but the cast is what makes it stand out. It was a very early role for both you and James Caan.

BD: And it was with Mickey Rooney! The only thing I remember about that… I knew Jimmy from when we played baseball together in Central Park in the Broadway show league. He was on another team than I was. He was in a play, I think, with a guy named James Luisi, and I was in Sweet Bird Of Youth. And when that ended, the Actor’s Studio had a team, and I was in charge of that. So I’ve known Jimmy since 1958, really.

On that show, Jimmy was kind of a surfer, driving through town, and Mickey Rooney was kind of a sadistic sheriff, and I was his sidekick. And he always took the belts of his prisoners as a keepsake as to who they were and what they might’ve been up to. So one day we were sitting around, and of course I wasn’t going to miss a chance to hear some of Mickey Rooney’s stories, so I was on him every day, and he was very gracious about it. And he was also unbelievably professional, considering what you hear about his reputation. He was just magnificent in terms of how professional he was.

So we’re sitting around one day and Jimmy, he’s been divorced for a little while, and he’s talking about girls he has been proficient with, if you will. This was the third day of it. And Mickey had had enough. He says, “Hey, Jimmy? Let me show you something.” And Mickey opens his wallet, and in it, the third or four sleeve of little pictures in his wallet, He says, ‘Look at that… and shut the fuck up!” It was a picture of an 18-year-old naked Judy Garland. Jimmy Caan never said another word. [Cackles.] And she wasn’t being promiscuous. She just didn’t have any clothes on!

Space (1985)—“Sterling Mott”

BD: Dick Berg and Stirling Silliphant were a writing team, and they did a great deal of those [anthology] series, but I did a miniseries called Space, about James Michener’s book. They wrote the script, and Dick was one of the producers. We shot it during the Olympic Games in 1984, so we couldn’t be in L.A., so we did it in England. I [effectively] play Chris Kraft, who was the first head of NASA. He’s one of the guys who went over to Peenemünde and brought back the scientists. So the series is about the history of space.

A year later, I was sent out on the road to sell Space, because it was going to be airing for five nights, for three hours a night, Sunday through Thursday, I guess it was. Our sponsor was the Astrovan. We were introducing the Chevy Astro van to America, so I went to the big Chevy place and we showed the 90-minute highlight reel of the whole series, and they all loved it. The stars in it were James Garner, myself, Michael York, Susan Anspach, Melinda Dillon… Everyone was respectable. That was a big deal for CBS.

Support Your Local Sheriff (1969)—“Joe Danby”

AVC: You’d worked with Garner before Space, having co-starred with him in Support Your Local Sheriff.

BD: Jim Garner was the nicest man I ever worked with in the business, bar none. Very bright, very full of energy, very funny. He was very funny. And people don’t know that he started his career on Broadway as one of the judges in The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial. He only had one or two lines, but that was his first show business job. His name then was James Bumgarner, and he was a great athlete in high school and a great golfer. And he was just so nice to me. Always nice to me, and always nice to Jimmy Woods, because… I don’t know, he thought we had something going on as actors, I guess. But he appreciated it. And he was quite good in those movies, Support Your Local Sheriff and Support Your Local Gunfighter, I think the other one was. Whatever they were called, he was good.

What was fun for me was that Support Your Local Sheriff was directed by Burt Kennedy, who had directed me in a movie with John Wayne and Kirk Douglas called… The War Wagon, that’s right. There were a lot of guys I got to work with because I was lucky enough to work in television when I started. One was him, and the other was a guy named R.G. Springsteen, who I worked with on a Wagon Train episode. Jack and I used to call each other up all the time and say, “Who’s the star of your show?” I’d say, “Scott Brady.” And he’d say, “Well, this week I’m working with Barbara Stanwyck!” “Oh, my God…” It was always somebody like that.

Chappaquiddick (2017)—“Joe Kennedy”

Swing Low (2017)—“Mallinckrodt”

White Boy Rick (2018)—“Grandpa Roman Wersche”

Mustang (2018)—“Myles”

BD: I just made a movie in Virginia in July. I don’t know if you know a guy named Terry Grennan, but he lives right outside Charlottesville in a farmhouse that he and his wife bought, and we made a movie called Swing Low. There are a bunch of guys who go to Sun Valley every year and have the festival and then live there in the winter because they like to ski, and he’s one of them.

I think we were there for three days. We stayed in one of those wonderful bed and breakfast places, but every night the racket was so bad that we couldn’t sleep, because there are these frogs that are on this huge estate, and they don’t do it ’til it’s dark, but when they start croaking, it’s almost deafening! I’ll never forget that.

But that movie’s not out yet. The movies I’ve got coming out that I give a shit about… Well, I give a shit about any movie I’m in, but of the ones that I know will get out, I made a movie with Matthew McConaughey called White Boy Rick. That’ll definitely come out. Chappaquiddick will come out, but not ’til next April. I think that’ll do well.

This movie I just finished last week is called Mustang, which is written and directed by a French girl named Laure De Clermont-Tonnerre. They were all French, but we shot in Nevada Correctional Center, the State Penitentiary for Men, outside of Carson City. How’s this for an idea for a movie? In Nevada, the prison has a program at that facility, and it’s the only one in America, because of the closeness to wild horses. I think you’re allowed to catch 13 wild horses a year, but the government catches them, then they bring them down to the prison, and every year 13 men can volunteer and get accepted into a program—and I’m the guy who runs the program in the movie—to train these horses for the U.S. Border Patrol. But they’re rehabilitating these guys, who… They’re not lifers, and they’re not murderers, but they’re violent offenders. Anyway, that’s what the story’s about. The program’s been going on for several years. So the movie asks, “Can the man break the horse, or will the horse break the man?”

The Driver (1978)—“The Detective”

Wild Bill (1995)—“Will Plummer”

Last Man Standing (1996)—“Sheriff Ed Galt”

BD: I’ve got time for one more before I have to leave you.

AVC: Well, a lot of readers wanted to make sure we asked you about both The Driver and Last Man Standing.

BD: Really? Well, that’s Walter Hill. I’ll go anywhere to work for Walter Hill. I’ve done three movies for him. I did The Driver, which starred Ryan O’Neal, Isabella Adjani, and Ronee Blakley. She was kind of an Altman-ite. Robert Altman loved her. But I liked her, too, because she was on the edge about everything in her life, and everybody else’s, so she could look you right in the eye, because she wasn’t bullshitting you, so you’d better no bullshit her. That’s why I liked her. And she was a very good actress, too!

I also did Last Man Standing for Walter, and I did Wild Bill, too. I just adore Walter. Adore him. He gave me a fabulous compliment once. We had a private screening at somebody’s house for Nebraska, and he came out, and he gave me a big hug.

He also directed some TV stuff, but his movies… I love Geronimo, I love 48 Hours, and I even love Southern Comfort, with Powers Boothe. He was very good to guys of my generation like Powers and myself, Ronny Cox, and Ned Beatty. He’s very loyal. And he writes very good stuff. And he can direct really, really well.

But that compliment? He came up to me as he was leaving the Nebraska screening with [Hill’s wife] Hildy, and he said, “Who would’ve ever thought that you would’ve become an American treasure?” [Laughs.] And from him, that’s great praise, because he’s one critical son of a bitch!