Is it too much to ask for a film about creative self-destruction to have a few loose screws of its own? Because Burnt is just about the toniest movie anyone could make about a recovering junkie throwing tantrums and lobbing pots and pans at people, its restaurant kitchen milieu given a culinary magazine gloss by John Wells’ conservative direction, the egos whiffing away when they could explode into full-on grease fires. With the exception of one indelible image of meltdown—a chef trying to suffocate himself by putting a sous-vide bag over his head—that comes too late to make a difference, Burnt lacks the emotional flush that would make it seem like something more than a quick, competent translation of a script by Steven Knight, who offers up yet another monk figure seeking redemption in the London backstreets. (See also: Eastern Promises, Dirty Pretty Things, and, uh, Redemption.)

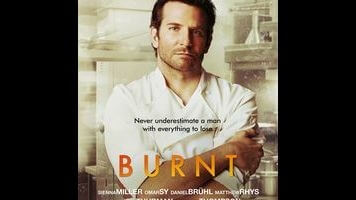

This time around, it’s Adam Jones (Bradley Cooper), former American bad boy of French cooking, who shows up in London after three years off the grid, having sworn off drugs and women, determined to finally earn a three star Michelin rating. Mind you, he doesn’t have a kitchen to cook in, let alone a restaurant, and for its opening stretch, Burnt basically runs like a heist comedy, with Adam assembling a team of old buddies (one of whom he actually picks up from prison) in order to strong-arm one Little Tony (Daniel Brühl) into letting him take over the Langham Hotel’s restaurant and re-make it from scratch. Any movie heist needs a rookie, who comes in the form of Helene (Sienna Miller), a talent scouted by Adam out of an Italian restaurant.

Like a few other movies scripted by Knight, Burnt feels like two acts missing a third, and its small pothole of a dramatic arc isn’t done any favors by Wells’ rushed and minimally personal approach, which allows just two small flourishes (one involving the Donnie Darko score, the other involving rack focus) between all the quick-cut back-and-forths and montages of modern London architecture, fancy kitchenware, and fancier food. Cooper’s charm, imposing post-American Sniper physique, and proficient French carry the movie, propped up by a very strong supporting cast (which includes Omar Sy, Emma Thompson, Alicia Vikander, Uma Thurman, and Matthew Rhys) whose roles mostly consist of fascinated or exasperated reaction shots. It just doesn’t carry the movie anywhere interesting.

Gourmet restaurant kitchens—in which competitive, obsessive personalities are locked in a room full of knives and open flames—are spaces of innate tension and high drama. But Burnt seems reluctant to push things too far, perhaps recognizing that monsters like Adam are at their funniest and most intriguing when they have no reason to change. At the same time, Burnt doesn’t have the guts to just let Adam Jones be. Though its soft-hearted ending doesn’t reach the Steve Jobs level of sentimental insincerity, it still feels like a big, wet fizzle: a life lesson about teamwork, learned by a character whose defining trait is the fact that he’s hit rock bottom over and over and always clambered out on the strength of his own ego. Perhaps Adam is just too good an asshole to be believable as anything else.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.