Burroughs: The Movie kicked off a short career by studying a long one

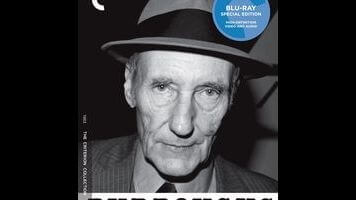

In 1989, director Howard Brookner completed his first narrative feature, Bloodhounds Of Broadway (starring Madonna, among many others). The film was a notorious critical and commercial flop, and Brookner, sadly, would never get the chance to make another—he died of AIDS-related causes just before Bloodhounds opened, a few days shy of his 35th birthday. However, he’d previously made a documentary about William S. Burroughs, which had premiered at the 1983 New York Film Festival. Originally intended as his thesis project at NYU (where his classmates included Jim Jarmusch and Tom DiCillo, both of whom worked on it), Burroughs: The Movie all but vanished after its initial screenings; for decades, it was available only via shoddy-looking bootlegs, the 16mm negative having disappeared. A few years ago, Brookner’s nephew, Aaron, raised the money to restore a print held by the Museum Of Modern Art, and this week the film is being released as part of the Criterion collection. It’s a belated happy ending for a filmmaker whose career and life ended before they’d even really begun.

Burroughs, on the other hand, improbably made it to age 83, despite having ingested enough heroin to kill several entire rock bands. The writer was already in his mid-60s, making a living primarily by performing readings from his collected works, when Brookner proposed making the doc, in 1978. What was supposed to be a brief collaboration wound up being extended for five years, during which time Brookner shot hundreds of hours of footage. The resulting film plays like a valiant effort to fashion something semi-coherent from all that material, but it never really seems as if Brookner had a vision for what Burroughs: The Movie should be. He simply found Burroughs fascinating, and who can blame him? The man’s insurance-salesman-gone-to-seed demeanor and creaky staccato rasp of a voice make for a hypnotic combination, especially if you’ve read Junkie, Naked Lunch, or The Nova Trilogy and are familiar with the casually outré nature of his prose. Few writers have ever come across as such a glaring contradiction.

Those who haven’t read Burroughs will get a small taste of the experience via The Movie, as Brookner includes numerous scenes of the author reciting his own work, both for audiences and just for the camera. What’s remarkable is how similar his extemporaneous speech sounds, even when he’s discussing such emotionally charged subjects as the death of his wife, Joan Vollmer, who took a bullet when Burroughs impulsively tried to shoot a highball glass off of her head à la William Tell. Granted, by this point, he’d been telling the story for more than a quarter-century, but there’s still something discomfitingly robotic about the way he articulates his most intimate memories and feelings, and in his interactions with his only child, William S. Burroughs Jr. (who died of cirrhosis of the liver, at age 33, while the film was being shot). By contrast, Burroughs comes across a bit more relaxed when hanging out with friends like Allen Ginsburg and James Grauerholz—the latter was essentially his caretaker over the course of his final years, though The Movie shows him functioning more like a fanboy/secretary.

With its copious talking-head interviews (other subjects include Brion Gysin, Patti Smith, and fellow Sgt. Pepper’s cover boy Terry Southern) and vaguely chronological structure, Burroughs: The Movie looks like a fairly conventional documentary, albeit one that rambles quite a bit. An attempt was made, however, to fashion something more in keeping with Burroughs’ “cut-up” literary technique, which created startling combinations of words by physically reassembling pieces of first drafts like jigsaw puzzles. The Criterion disc includes, among its supplements—audio commentary by Jarmusch; outtakes; a Q&A from the film’s second NYFF appearance last year—a 23-minute alternate version of the film that verges on avant-garde. Assembled by photographer and aviation inventor Robert Edison Fulton Jr. in 1981, it was deemed too aggressively uncommercial, and wound up being shelved; arguably, though, the way that Fulton’s cut skips across Brookner’s years of footage, like a stone across the surface of a lake, more accurately reflects and captures its subject’s essence. In any case, that footage can finally be seen again, in whatever form one chooses, without recourse to the sort of hip video store that’s now an endangered species. And the forthcoming Sundance Film Festival will include a documentary about Brookner himself, directed by his nephew: Uncle Howard. It’s been a long time coming.