Burt Lancaster swims across time and space in a surreal, one-of-a-kind Hollywood movie

Watch This offers movie recommendations inspired by new releases, premieres, current events, or occasionally just our own inscrutable whims. This week: Antlers, a horror movie adapted from a story by Nick Antosca, is not hitting theaters. In its absence, we’re looking back on other movies based on short stories.

The Swimmer (1968)

John Cheever’s “The Swimmer,” originally published in the July 18, 1964 issue of The New Yorker, sends its protagonist on one of the oddest, most ambiguous odysseys imaginable. It’s the sort of purely literary conceit that seems impossible to divorce from the page and a reader’s imagination… yet four years later, it somehow became a Hollywood movie, released by a major studio (Columbia) and featuring a major star (Burt Lancaster). Married couple Eleanor and Frank Perry—she wrote the screenplay, he directed—took advantage of the confusion and uncertainty of an industry in transition, shortly before Easy Rider blew the prevailing paradigm wide open and ushered in the American New Wave. The Swimmer arrived in theaters at perhaps the only historical moment at which its existence as something other than a micro-budget indie would have been possible, and it remains a gloriously bizarre anomaly in the history of studio filmmaking.

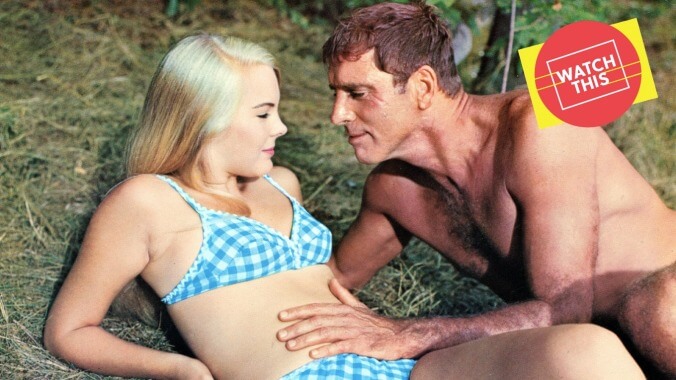

Cheever’s story is at once simple and slippery. On a warm summer day, after taking a dip in a friend’s pool, Ned Merrill looks out at the landscape in the direction of his own house and “seemed to see, with a cartographer’s eye, that string of swimming pools, that quasi-subterranean stream that curved across the county.” He decides to swim home, portaging his way from one pool to the next, saying howdy to his neighbors en route. One might expect this structure to produce a diverse series of dramatic encounters, and in the movie version, particularly, it does: Ned (Lancaster) walks for a time with a young woman who used to babysit his kids (and confesses to having harbored a secret crush on him, thereby activating his middle-aged creep mode), doffs his trunks at the behest of a naturist couple, and gets an exceedingly cold shoulder from a woman with whom he’d once cheated on his unseen but frequently mentioned wife.

That’s plenty of incident, even for a feature-length film—the Perrys expand into full scenes what Cheever sketches in just a sentence or two, and invent numerous characters from whole cloth. But they also honor the story’s subtly surreal nature, in which Ned’s journey moves him through time far, far more quickly than through physical space. Both on the page and on screen, others make comments that Ned finds nonsensical, referring to financial and marital difficulties of which he has no memory. With each successive swimming pool, his status in this affluent community seems to shrink, until eventually one gets the impression that many years’ worth of failure and downward mobility have elapsed over the course of a single afternoon. Cheever originally had a novel in mind, but wound up writing a short, sharp shock.

The movie, on the other hand, feels quite novelistic, thanks to its often literally fleshed-out humanity. The Perrys do make a couple of ill-advised choices in its opening scene: Eleanor cuts Ned’s wife, Lucinda (who has clearly not left Ned at the beginning of Cheever’s story, though she’s long gone by the end of it), while Frank has the supporting cast exchange significant, worried glances when Ned brags about his good fortune. Together, those touches undercut the material’s Twilight Zone aspect, offering the more, ahem, prosaic possibility that Ned’s life went into the toilet some time ago and he’s merely in denial. Otherwise, though, the conceit arguably works even better at greater length, with more breathing room between oblique suggestions that various details of Ned’s existence have altered since the previous pool. And Lancaster, still incredibly fit in his mid-50s, was the ideal choice for a character gradually coming to terms with the vast gulf between his self-image and reality. His performance starts out all swagger and grows ever more pathetic as the film progresses, even as Frank Perry’s ultra-’60s formal approach—gauzy filters, blurred focus, multiple superimpositions—creates a visual correlative to that loss of conviction. It’s genuinely jarring to see such a tower of strength reduced to pounding at the barren threshold of the good life he remembers.

Availability: The Swimmer is currently available for digital rental and purchase via Amazon, Google Play, YouTube, Fandango Now, Vudu, and Microsoft.