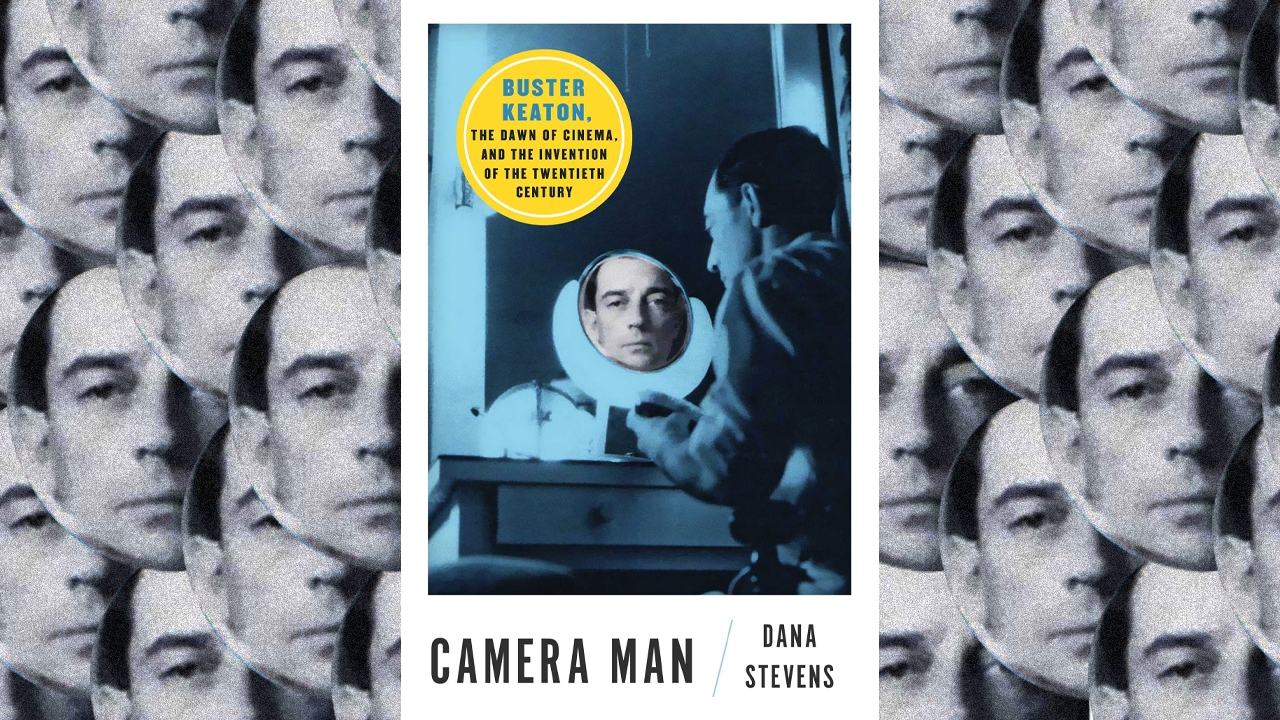

Cover image: Atria Graphic: Natalie Peeples

Joseph Frank Keaton—the silent film star belovedly known as Buster—was born the same year, 1895, that the Lumière brothers unveiled the first moving pictures to an audience of stunned Parisians. It’s a nifty bit of trivia and a clever narrative framing device in Dana Stevens’ Camera Man: Buster Keaton, The Dawn Of Cinema, And The Invention Of The Twentieth Century, a triple biography of sorts whose subtitle summarizes her story well.

Buster Keaton was not only an early filmmaker of extraordinary ability, Stevens contends, but his life and work act as a lens through which to view the emergence of cinema and the arrival of the American Century. Camera Man is an essential read if you’re interested in any of these topics, and a terrific starting place for the budding Busterphile.

Though Keaton and cinema share a birth year, Baby Buster’s birthplace of Piqua, Kansas was just another humdrum circuit stop for his struggling vaudevillian parents, Joe and Myra. He performed acrobatic feats; she played the cornet. “The act didn’t go,” read one review. “’twas bad.”

Buster joined the family act when he turned 5, bouncing a basketball off his father’s head for laughs. Joe’s scripted reaction involved seizing a suitcase handle sewn along the spine of his son’s costume and chucking the boy across the stage. He was a “human projectile hurled into the twentieth century,” Stevens writes. Three years before the Wright brothers flew, the pint-sized prop known as Buster soared through the air.

The Keatons now performed as a trio, earning the family an extra ten bucks per week and rave reviews. “An infant phenomenon,” rang one trade. Advertisements billed Buster as “The Boy Who Can’t Be Damaged.” “You think you were treated roughly as a kid,” read one ad. “Wait till you see how they handle Buster.”

“Keep your eye on the kid,” Joe Keaton advised audiences, having coached the young Buster to receive his rough handling without a wince or smile. A “poker-faced, rubber-bodied” star, in the words of Stevens, was born.

This abuse secured the attention of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, a two-year ban from performing in New York, and enduring showbiz apocrypha involving Buster’s unbruisable body, often propagated by the actor himself—most famously the myth that Houdini bestowed the nickname “Buster” after witnessing the toddler tumble down a flight of stairs.

Buster, alongside his mother, abandoned the alcoholic and increasingly volatile Joe in 1916, despite apprehensions about going solo. “What a beautiful thing [our act] had been,” he remembered decades later. “Beautiful to see, beautiful to do… but look at what happened, standing up and bopping each other like a cheap film.”

Luckily, Buster soon fell in with Roscoe Arbuckle, playing the pork pie-hatted third banana in a series of two-reels alongside the early comedic actor known as Fatty. Though these were bit parts, Buster’s “body, always in motion, often in peril,” Stevens writes, “was always at the crux of the action.”

After filming 15 shorts with Fatty, Buster partnered with Arbuckle’s producer to open his own studio. His early independent films feel like they’re building cinema from the ground up, while simultaneously deconstructing the moving image through celluloid-shredding mayhem. Witness the Rube Goldbergian set pieces of his 1920 masterpieces: the DIY house in One Week, the dinner scene in Scarecrow, and the wooden fence hijinks of Neighbors. Or relive the groundbreaking feats from his feature-length gems: climbing into the movie screen in Sherlock Jr., trusting physics in Steamboat Bill, Jr., and crafting arguably the greatest cinematic chase scene of all time in The General.

To watch Buster perform is to ask not only “How did he do that?” but “Why would he do such a thing?” His films don’t contain the pure pathos of Charlie Chaplin, yet they aren’t purely moronic slapstick. His work is subversive, winkingly anti-authoritarian without being socially or politically satirical. Buster disrupts, in most every film, the feigned stability of home and family. He is a wordless whirligig in constant motion, trying to outrun cops, women, thieves, trains, and even the wind.

“He can impress a weary world,” one critic-fan wrote in 1922, “with the vitally important fact that life, after all, is a foolishly inconsequential affair.”

Stevens does a fine job chronicling the weary world that was America in the early 20th century. There are chapters on the gender imbalance among Hollywood filmmakers (“a higher percentage of American movies were directed by women in 1916,” she notes, “than has been true in any year since”) and the ubiquity of Blackface (one film historian counted 18 separate jokes related to race or ethnicity in Buster’s 1920s output). Stevens also traces the rise of the film critic, the evolution of modern celebrity, and the transformation of film from “a novelty to be gawked at for its own sake” to an industry where individual films now often gross billions. Only a drawn-out chapter covering Buster’s parallels with Hollywood wannabe F. Scott Fitzgerald—though the two likely never met—feels like filler.

Perhaps inevitably, Buster could only soar so high. He signed with MGM, despite warnings from his silent comedy rivals, Chaplin and Harold Lloyd, and made derivative, often dreary films that were almost always box office triumphs. He took comfort in a bottle-a-day whiskey habit, divorced, married his sobriety nurse while on a Tijuana bender, and squandered his contract. Years later, he would describe this period as being “on top of the world—on a toboggan.” Yet, Camera Man traverses the lows of Buster’s middle years to find hope in his artistic and critical renaissance in the 1950s and ’60s.

“Who was this solemn, beautiful, perpetually airborne man,” Stevens asks. He was the one and only Buster Keaton.