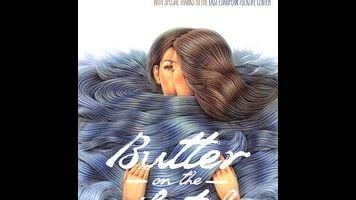

Butter On The Latch and Thou Wast Mild And Lovely make an eerie double feature

Josephine Decker’s first two narrative features make for a heady, dreamy double bill for anyone patient enough to tease some meaning from their madness. Butter On The Latch and Thou Wast Mild And Lovely seem to take place in separate but similar worlds where the boundaries between waking and dreaming, intimacy and violence, are all too permeable. Ashley Connor’s cinematography works wonderfully with Decker’s editing to create a weird dreamscape that feels like Picnic At Hanging Rock populated by adult women.

Butter is an improvised work that’s loosely about two friends (Sarah Small and Isolde Chae-Lawrence, using their real first names on-screen) who go to a Balkan music festival in the forests of Mendocino, California. Their relationship is somehow fraught, although it’s not perfectly clear how or why, and it begins to disintegrate when Sarah takes a liking to a camper named Steph (Charlie Hewson). The different techniques Decker uses—the improvised dialogue that feels like listening to one side of a phone conversation, the woozy cinematography and sound design, the disorienting editing—create a sense of claustrophobia. The film’s world is beautiful and scary, but also as intimate as a childhood sleepover.

Thou Wast Mild And Lovely, which Decker co-wrote with David Barker, is more formal in structure. If Butter is the wild forest of the female psyche, Thou Wast Mild reads as the fertile rolling farmland where sex and death are cuddled right up next to the miracle of life. Sarah (Sophie Traub) lives with her dad Jeremiah (Robert Longstreet) on a farm out in the middle of Kentucky. There’s something a little off about them from the start—they’re not quite incestuous, but their boundaries are too permeable, their roughhousing not entirely innocent. Jeremiah hires Akin (Joe Swanberg) to help out with chores over the summer, but it’s clear as soon as Akin carefully takes off his wedding ring before entering the house that he’s not going to be just another seasonal worker.

The masculine posturing between the two men and uncomfortable sexual tension between Akin and Sarah move the story along nicely, but the editorial techniques that made Butter’s loosey-goosey narrative work so well undermine Thou Wast Mild. There are a few too many experimental flourishes to effectively build the sort of tension that’s necessary to really make the ending pay off. Traub’s Sarah is fascinating, with an almost feral sexuality that makes her the most crucial component of the movie. But Swanberg’s Akin is too much of a cipher to be interesting, and Longstreet’s Jeremiah isn’t very memorable either. Still, it’s hard to shake the film off, or to shake off Butter On The Latch either. Decker’s DIY audacity, and her flair for the otherworldly, make her a filmmaker to keep an eye on.