The Cold War is a conflict so easily distilled into symbols and metaphor, because neither side ever entered into direct, wide-scale conflict with the other. There was fighting, and the covert nature of that fighting has lent a sense of mystique to the spy fiction produced during and after the conflict. But on both sides of the Iron Curtain, the enemy was kept purposely vague. Whole generations of Americans grew up fearing an invasion led by the caricatures captured on Soviet-era propaganda posters, channeling that anxiety into oblique and fantastic bogeymen like the pod people of Invasion Of The Body Snatchers or James Bond’s many Communist-allied foes. In the USSR, the American way of life broke down into ready-to-detest symbols like the dollar sign or the cross.

Larrick is such a terrifying threat, specifically, because he’s unbound by one of The Americans’ favorite themes: Loyalty. His coldly mercenary tactics make him the perfect foil to Rhys’ character and Noah Emmerich’s Stan Beeman, men fighting for separate countries who spend a sizable portion of season two in conflict with their assignments and themselves. Originally presented as a stand-up, Captain America-type, Stan’s ready to go turncoat when the life of his lover at the Rezidentura is threatened. Rhys, meanwhile, spent consecutive episodes improving on one of TV’s best performances by finding new ways to voice and display the inner turmoil of a soldier losing touch with his cause. A series of conversations with increasingly desperate men demonstrated the true cost of Philip’s line of work, a clever complement to scenes in which Russell speaks to her scene partners while Elizabeth is really psyching herself up.

Funhouse reflections of the Jennings are scattered across season two, 13 episodes that begin with the murders of another “couple” assembled by the matchmakers behind Directorate S. One minor arc finds Elizabeth mentoring an eager Sandinista, a surrogate daughter who arrives just as Elizabeth’s biological daughter is distancing herself from her parents. Domestically, The Americans’ second season unearths poignant and inventive material, stories that ponder the extent to which children can truly know their mothers and fathers, all the while using the Jennings’ background to come at teenage rebellion from unique angles. Holly Taylor gets to play the first TV adolescent for whom an interest in Christianity is an affront to everything her parents believe in, an ingenious twist on an old story that puts Philip and Elizabeth in the crosshairs of the ideological menace they never saw coming.

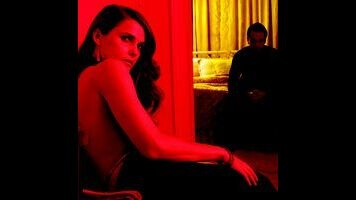

Episode nine, “Martial Eagle,” uses Paige Jennings’ burgeoning faith as one of the season’s many thematic ties to its assignments involving stealth technology—Paige’s youth-group activities initially go undetected—though Rhys is anything but covert when Philip has had his fill of God and Jesus. His outburst in the Jennings’ kitchen (American television’s most fraught domestic space) is season two’s equivalent to last year’s “Show them your face!”—a moment that genuinely startles even as it edges toward outright camp. It’s moments like these that disprove the notion that The Americans is an exercise in basic-cable cold-bloodedness; alternately sultry and unsettling, “Behind The Red Door” plays like an hour-long antidote to this impression. Fictional spies have always had a strange relationship with sex, and the season’s sixth episode takes that to new extremes, testing the limits of Philip and Elizabeth’s romance while further blurring the lines between the people they are with each other and the people they are for their jobs.

If only the vulnerability on display in that episode was extended to every other aspect of the Jennings’ lives. As the season-two body count mounts, there’s the feeling that the writers pivoted from Elizabeth’s near-death experience in the first-season finale toward placing an infinite supply of human shields between the show’s protagonists and those who wish them harm. The collateral damage does compelling work on Philip’s mental state, but Larrick lays waste to so many recently introduced characters that there’s little fear that any of the regulars might be next. (Compare that to last year, which used the sudden and startling death of Stan’s FBI partner to catalyze emotional and narrative beats that spill over all the way to season two’s final episodes.) The increased tension in season two sometimes suggests that Paige or Henry might be the next to go, but that’s a line the show isn’t willing to cross just yet.

Besides, that’s a move for a coarser, shock-for-shock’s-sake program. The Americans is more patient, more willing to stretch mysteries like stealth or the Connors’ murders across an entire season, fortifying those storylines with shifting relationships and alliances like the uneasy arrangements struck between FBI operatives and their KGB counterparts in season two. One reveal in the finale expertly swaps fear for the Jennings kids for fear of the Jennings kids, laying pipe for a third season in which Paige gets all of the answers she sought across the past 13 episodes—at a considerable cost. She just might prove to be a more formidable foe than Andrew Larrick ever was.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.