Bobby, who has ambition but not direction and moxie but not much talent, basically begs for a job from his hotshot uncle, power agent Phil Stern (Steve Carell, not quite right for this breed of cad). Once employed, the young man promptly falls in love at first sight with Phil’s secretary, Vonnie (Kristen Stewart, lit like an angel), unaware that she’s carrying on a secret affair with her boss. Allen, never shy about paying homage to his influences, is partially reworking one of the greatest comedies in Hollywood history, Billy Wilder’s The Apartment. (There’s even a New Year’s Eve scene, in case the plot parallels weren’t plain enough.) If the comparison isn’t flattering (how could it be?), the director enriches his romance by exploiting some preexisting star chemistry: Café Society is the third film to pair Eisenberg and Stewart (after Adventureland and American Ultra), and the two make a perfunctory courtship feel unstudied, even natural—no small feat, given that they’re delivering latter-day Woody dialogue during their map-to-the-stars dates around L.A.

Of all the leading men Woody Allen has ever cajoled into basically doing a bad Woody Allen impersonation, Eisenberg may be the only one who’s preserved his own distinctive personality in the bargain. That could be a product of practice: Eisenberg, after all, already filled Allen’s loafers in To Rome With Love, playing the kind of smitten young nebbish the filmmaker used to write for himself, before (and some time after, to be honest) he got too old for the part. But it’s probably also because “imitation Woody” is just another shade on Eisenberg’s color wheel of neurotics. (He only has one scene where the strain of doing Woody really shows; it’s a failed rendezvous with a prostitute that’s easily the broadest bit of comedy in the movie.) Stewart has the trickier task of making a person out of an object of desire, and though Allen eventually betrays the character’s spirit for the sake of a larger point about fluctuating ideals, the actress still radiates a distinctly down-to-earth charisma.

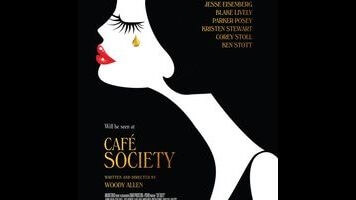

For critics on the Allen beat, the challenge of evaluating each annual effort—produced out of something closer to habit than passion—runs deeper than navigating around the ongoing controversies of his personal life. How does one find fresh words to lament the creative atrophy of an artist who’s been operating well below his prime since at least the turn of the century? How do you regularly identify this legendary filmmaker’s habit of repeating himself without repeating yourself? Café Society offers at least one fresh element to latch onto: It’s Allen’s first feature with revered Italian cinematographer Vittorio Storaro (Apocalypse Now, Last Tango In Paris), and the first time both artists have shot a feature on digital instead of celluloid. Woody has long leaned on his DPs to supply some visual elegance to his urbane gabfests, but Storaro goes above and beyond, giving everything from an early-evening pool party to a cramped Bronx apartment an inviting, nostalgic luster—the perfect look for a film set in an idealized past and one about wistful remembrance.

Café Society eventually shifts from the city of angels to the city that never sleeps, as Bobby gets involved in a swanky Brooklyn nightclub run by his gangster brother (Corey Stoll), the film’s sunny West Coast days bleed into hopping East Coast nights, and the scope gently expands, years passing in a blur of success but also nagging regret. Maybe it’s that Allen has been on autopilot for so long that any show of ambition feels significant, but there’s a certain lingering power to this lament for romances expired, paths not taken, and the way everyone inevitably changes over time. Woody, now in his 80s, narrates the movie, which lends it a vaguely, symbolically autobiographical slant. Is he looking back on his past, pining for the filmmaker (or even the man) he used to be? Any viewer who’s soldiered through Allen’s late period, beating the heat every summer with the mood-setting jazz of another star-studded throwaway (dubious “comebacks” included), will know the feeling.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.