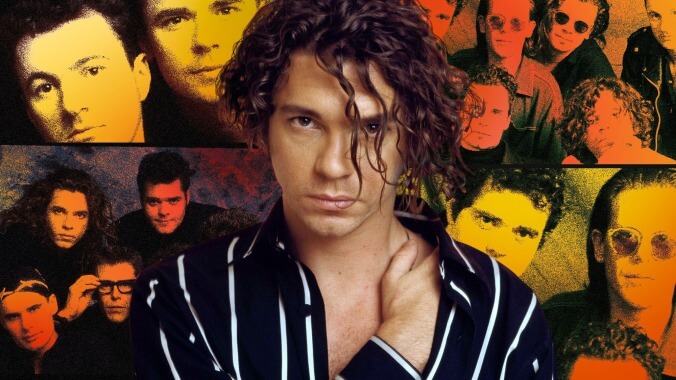

Calling all nations: 60 minutes of INXS’s non-hits that show why they’re rock icons

Image: Graphic: Natalie Peeples

There was always something a little disreputable about INXS. Despite being one of the bigger rock bands on the planet for the better part of a decade, releasing a string of critically and commercially successful albums worldwide, the Australian six-piece never really shook the perception that it was more style than substance, a band that could generate frothy pop hits but which lacked the kind of depth that would bestow long-term credibility on its music. Maybe it was the influence of dance music on the group’s sound; for reasons involving cultural and racial bias, the genre was considered less artistically meritorious during INXS’s heyday, in the ’70s and ’80s. Or perhaps it was the overt sexuality and louche nature of the band’s lyrics and style; unless you were Mick Jagger, such topics rarely earned lyricists much acclaim. You could argue INXS was the Maroon 5 of its era—a massively popular act that few appeared eager to defend or even admit to liking outside of a few catchy singles. (It’s not exactly surprising to learn that Maroon 5 cites the group as an influence.)

Except there’s a crucial difference: INXS has songwriting chops for days. Even in the band’s earliest dancehall years, when it sounded more like British new wave than the slick, soul-glam pop that would later generate international success, the group’s penchant for simple yet original melodies and deceptively clever arrangements made it stand out amid the endless glut of like-minded musicians eager to find an audience. If there’s a clear through-line from INXS’s 1981 self-titled debut to its latter-day material, it’s that the group knew how to mine pop music’s most appealing elements for maximum effect. Their songs pushed glitzy sheen, hummability, and nursery-rhyme repetition long before producers like Max Martin and the modern pop algorithm machine made such things the foundation, rather than ornamentation, of the music. And while it’s easy to lump such tactics in with the nefarious insipid-earworm strategies of, say, The Black-Eyed Peas, INXS had the musicianship to back it up, and was able to transform its addictive music into elegantly crafted anthems greater than the sum of their parts—and always with just enough of an oddball edge to keep the songs from tipping over into soulless bombast.

Just as importantly, INXS had a bona fide rock star at its center. Michael Hutchence came across as someone genetically engineered to be a rock icon, all smoldering charisma and come-hither sexuality, yet his persona was far enough removed from bland male-model looks to maintain an aura of enigmatic cool. To see him strut and sway in music videos or onstage—maybe the Jagger comparison is apt, after all—was to see someone made to command a crowd. As a lyricist he may have lacked the poetic voice of many of his contemporaries, and INXS has nothing if not a surfeit of songs about how good you look, girl, and how beautiful you are, and how everything’s gonna be all right, baby; but from such sentiments are classic pop songs born, and anyone who has heard the group’s stirring hits like “Never Tear Us Apart,” “Need You Tonight,” or “Don’t Change” can attest to the power of his delivery.

Still, there’s an unmistakable bent to the group’s sound, and it’s that of the 1980s. Right up until Hutchence’s death in 1997, everything the band recorded sounded like it could’ve sprung, fully formed, from the synthesizer-and-gated-snare world of pop production in the neon decade. Elegantly Wasted, the band’s last album with Hutchence, was an explicit attempt to recapture the late-’80s sound that vaulted them to superstardom. It brought them success, but it also damned INXS to right-place-right-time assessments about its ultimate worth. The band’s dogged efforts to capitalize on the dominant trends of its time—at least, until those trends became passé alongside the group that benefited from them—also relegated it to a position as one of rock’s runner-ups. There’s no spot in the Rock Hall Of Fame for INXS, which is a shame; as the following 60 minutes of music demonstrates, the Australian act is richly deserving of posthumous accolades and a place in history. We’ve deliberately omitted any hits that many are already familiar with—nothing that made the Billboard top 100, and nothing in the group’s top five of most-listened-to tracks on Spotify. But beyond the gloss of INXS’s hits is a musical document of a band that hid powerful music beneath a glamorous facade.

“Heaven Sent” (1992)

[pm_embed_youtube id=’PLslxeOGneMPvgZR_h6mVhW38dWx123_Ai’ type=’playlist’]What better way to dive deeper into the INXS catalog than with a song that announces its ass-kicking intent right from the outset? Perhaps the band was simply trying to keep up with the times, but the dirtier, more experimental production on 1992’s Welcome To Wherever You Are led to a creative resurgence—and one of the finest records of the band’s career, certainly the best of its ’90s output. That began with “Heaven Sent,” the second track on the album (though arguably the first “real song,” following the minimalist thrum of “Questions”) and a barn-burner that stands alongside the most raucous of the group’s hard-rock-inspired music. Lyrically, it’s classic seductive Hutchence—an ode to his then-love interest, Danish supermodel Helena Christensen—but it also fumes and fuzzes with a tempestuous urgency rarely heard in the band’s oeuvre.

“I Send A Message” (1984)

The Swing was INXS’s fourth album and its first truly superlative one, where the band became confident enough to embrace the minimalism that would become its hallmark in the era, defiantly standing on the “less is more” track. Song three, “I Send A Message,” takes another step back as Hutchence’s vocals assume center stage with minor competition from the percussion, occasional synth chord, or haunting sax line. Yes, the lyrics are mirror-shallow, as Hutchence sends a psychic signal to his intended, but the beat is irrepressible, and his sly “Go ahead, Timmy” to introduce Tim Farriss’ angsty, eruptive guitar solo indicates he’s willing to hand over the spotlight—but only for a moment.

“Stay Young” (1981)

The young INXS catapulted from genre to genre to see what would stick, as seen in the first single off their second album, Underneath The Colours. “Stay Young” is a simple, idealistic plea, aided by a heavy ska influence on the percussion and backing vocals. The song’s atmospheric guitars helped the single glom on to the emerging new wave sound of the ’80s; while the lyrics start out with the typical INXS theme of “you look so good girl” (“Keep that biting lip / Know what I mean”), the unexpected call of “Stay young / Just this once” manages to land, and the track’s beach-party exuberance makes that request almost seem possible.

“One X One” (1985)

INXS learned to lean into the rhythm and blues-rock swagger that defined a lot of ’80s pop. After its new-wave sounds gave way to the increasingly artful pop orchestrations of The Swing, the band began mining a harder-edged vein of rock on Listen Like Thieves, combining Rolling Stones licks with soulful horn-and-synth rave-ups in a manner that brought out the best of both styles. It led to an international breakthrough and the group’s first Stateside hit (“What You Need,” its Billboard top-five debut), but it also delivered “One X One,” a victory strut of a song that finds Hutchence once more implying that, after everything else is done, wouldn’t you rather be spending all night with him? The man played to his strengths.

“Elegantly Wasted” (1997)

The title track from the band’s last album before Hutchence’s death seems like a sad bookend to the much earlier “Stay Young.” INXS was attempting to recapture its sound of youthful exuberance (“Why don’t we make it rain like we used to”), but the haunted dance club vibe of “Elegantly Wasted” suggests those days are long gone. But those now-jaded guitar hooks still have a significant amount of power, as they erupt into the bombastic declaration of the song’s title; to the end, Hutchence’s commanding vocals indicated that he was aware of just how far afield the band had strayed, and possibly how much more fun things were at the beginning, protesting, “This ain’t the good life.” A poignant last gasp (yes, they made more music after Hutchence’s death, but it’s not the same) that shows that while the band’s strengths faded, they stayed remarkably intact.

“By My Side” (1991)

“By My Side” is maybe the best example of one of INXS’s least appreciated talents: blending smoky, torch-song balladry with Beatles-esque compositions. It begins with guitars and piano work that wouldn’t be out of place on The White Album, before making a hard pivot into soulful, late-night confessional, Hutchence’s near-whispered croon maintaining just the right amount of rasp before exploding into the refrain’s lament. Whereas Kick’s “Never Tear Us Apart” kept the vibe of a band in full-on lounge-lizard groove, here it goes the opposite direction, incorporating the strings-led swell of Australia’s Sydney Symphony Orchestra to turn the song into something that outstrips the bonds of its 3/4 swing—a lighters-in-the-air anthem with a bombast that never strays far from its simple hook. It’s not surprising to learn it’s one of the two INXS songs played at Hutchence’s funeral.

“Black And White” (1982)

“Black And White” is a prime example of INXS’s undeniably ’80s sound: It folds the ska influence of the band’s earlier work into a bold percussion/axe line, providing a solid foundation for a series of experimental synthesizer emissions that sound like keyboardist Andrew Farriss having fun with a new toy. As the song tries to get at the heart of a confounding relationship, the irregular (and very ’80s) sound effects evoke the chaos of trying to get a handle on emotions that your heart is rapidly losing control of. Hutchence’s emotive voice is exemplary as always, but the group vocals indicate the high level of musicianship the band boasted across the board.

“Make Your Peace” (1993)

The making of Full Moon, Dirty Hearts was fraught with tension, in large part due to a strange and unfortunate injury: After a drunken late-night altercation with a cab driver, Hutchence suffered a skull fracture, which, along with a temporary loss of smell and taste, caused him to behave erratically, often lashing out in violent and unexpected ways. In the liner notes to the group’s Anthology compilation, Andrew Farriss recounted the story of Hutchence shoving his mic through the strings of an acoustic guitar, yelling, “We need more aggression on this track!” It’s unknown which song the singer was referring to, but one could easily imagine it being “Make Your Peace,” a raw, four-on-the-floor stomper of a dirty blues riff with a shout-along refrain. It’s a strong example of the band’s penchant for taking funk-derived licks and rhythms and transforming them into arena-rock bangers.

“Calling All Nations” (1987)

In 1987, you had to wonder if it was worth purchasing the album Kick, since it seemed like the entire volume was played regularly on the radio. But such was the creative alchemy behind that blockbuster release that even the non-hits still rank pretty high in the group’s catalog. To start winding down the album, Hutchence pulls off the most unlikely of vocal feats—the dreaded talk-singing—to put second-to-last track “Calling All Nations” over. Naturally, a plea from INXS for world unity is based on an invite to “Come on down / To the party,” urging everyone to flee their everyday shackles of the “axe to the wheel” to “do the sex dance / ’Cause it’s necessary.” By that point in the album, “Calling All Nations” just seemed like the next logical step: dominating the world, and having the best time doing it.

“Just Keep Walking” (1980)

INXS’s first album shows a band still grappling for its own sound, the members’ youth making them sponges for musical trends. This all-over-the-place identity is clear in the band’s first single, “Just Keep Walking,” which shows a clear art-punk influence in the angular riff of the chorus, while the more melodious verses more aptly predict the band’s future. Nasal vocals, sharp keys, and primitive percussion inhabit the spaces the group’s horn sounds would eventually occupy, with Hutchence feeling his way toward the front, but not quite there yet. Still, it’s a fun exploration of a different, more barbed sonic path the band could have taken; even though it barely resembles what most people would identify as INXS’s dance-laden sound, “Just Keep Walking” became the band’s first top 40 hit in its native Australia.

“Biting Bullets” (1985)

Few songs straddle the line between the first phase of INXS’s career and its star-making second act as well as “Biting Bullets,” a frenetic rocker about watching those around you losing their personal battles—and wondering if you’ll be next. You can hear it in the organ-like synths that kick it off, a callback to the days of “Just Keep Walking” and the new wave bar hall beats of the first few albums. But it quickly introduces a catchy, ascending guitar riff, combined with a simple sing-along refrain that takes the song from generic rocker into cathartic anthem. The rare track co-written by Hutchence and the band’s saxophonist, Kirk Pengilly, it locates an appealing middle ground between those competing influences, exemplifying the transitional phase that Listen Like Thieves occupied between scrappy Aussie upstarts and world-class rock and roll.

“Lately” (1990)

X is often unfairly maligned as a Kick redux, a dose of diminishing returns from the same well of dance-rock inspiration that doesn’t stand up to its predecessor. But while it’s probably unfair to expect anything to achieve the same heights as INXS’s global smash and pinnacle of success, it’s equally silly to pretend the band was reinventing the wheel here—instead, X sounds like nothing so much as a well-oiled group delivering more of the sound it had come to master. And in terms of slick but angular ’80s grooves, “Lately” might be the best of the record’s bunch. The lyrics may conjure up a state of hesitant uncertainty (“Lately, you look around / You’re wondering what you’re doing”), yet the music is anything but.

“Full Moon, Dirty Hearts” (1993)

There was a darkness that sometimes cropped up in INXS’s music, a sense of bleak foreboding that suggested the end of the night may be just the beginning for those still looking for more than what they have. You can almost hear the last-call despair emanating from “Full Moon, Dirty Hearts,” the title track off the band’s penultimate release with Hutchence. A sultry, soulful torch song, the track incorporates the brilliant touch of having Pretenders singer Chrissie Hynde match Hutchence line for line, her smoky alto the perfect pairing with his rich baritone. It felt a little like a song out of time upon its release, a throwback to an era when Tom Waits was still a young man behind a piano, but now it just sounds timeless. Plus, check out a very young Ben Mendelsohn in the accompanying video.

“Jan’s Song” (1982)

INXS wasn’t concerned as much with the political as the partying, which makes “Jan’s Song” a bit of an early career outlier. The Shabooh Shoobah cut paints a portrait of a young girl headed for protest, “calling from the rooftops” about “Her people’s needs / Their basic rights.” The band was still feeling out its “less is more” approach; Pengilly’s plaintive sax sounds like a pied piper leading this undeniably fashionable revolution, putting the emphasis on “generosity” and “democracy” while embracing the shiny, untarnished idealism of youth, when “you’ve nothing to fear.”

“Back On Line” (1992)

“Have you ever felt the moment / When you’re losing all control?” In this Welcome To Wherever You Are track, Hutchence abandons his paeans to love, sex, loss, and uncertainty, and pens one of the most purely determined and optimistic songs in the band’s catalog. From the airy, almost shoegaze-like guitars, to the steady, Spiritualized-esque pulse of the bass, to the rousing, major-key melody, “Back On Line” works as a warm, enthralling tonic to the oft-carnal vibe of the band’s saucy aesthetic. It’s a song that recalls the music of U2, drawing a clear line from one arena-ready act to another. And while U2 would continue to breathe that rarefied superstar air while INXS’s star waned, tracks like this help show how the two acts could stand toe-to-toe for a number of years.

“Melting In The Sun” (1984)

INXS kicked off album number four, The Swing, with its eventual hit single, “Original Sin,” and kept the momentum going with the minimalist rage of “Melting In The Sun.” Drummer Jon Farriss (so often the not-so-secret weapon of the band) offers a plodding yet commanding percussive line, creating negative spaces that the band ably fills with odd guitar creaks and the random synth chord. The surprising chorus manages to pull it all together, with a monklike chant warning against “great expectations” that fail to be realized in the harsh, burning landscape—it’s the washed-away dreams of “Original Sin” turned into a bleak reality.

“Tiny Daggers” (1987)

How to wrap up a blockbuster? You could do worse than the deceptively cheery “Tiny Daggers,” reportedly written by Hutchence for his struggling brother Rhett. Kick’s last song is a strong argument that the best way to lure someone away from the dark side is an irrepressibly hooky pop song, with sunny synths, an effervescent guitar line, and overlapping vocals leading the way, concluding the album with an exultant flourish. After the exhausting emotional highs and lows of Kick, INXS goes out on a wave of buoyant energy, even cheekily adding a nod to the album title: “All you want to do is kick it in / All you got to do is walk right in.” On any other record, it would have been a hit single.

“The Swing” (1984)

INXS closed out side one of its breakthrough fourth album with this dramatic title track. “The Swing” showed songwriters Hutchence and Andrew Farriss delving into some bigger picture questions as the band’s exemplary musicianship is on full display. Drummer Jon Farriss takes control from the start, as a faint but persistent drumbeat eventually builds into an unstoppable force, aided by the wail of his brother Tim’s guitar. The ferocity of these intersecting beats reflects the conflict at the heart of “The Swing,” as Hutchence rails against the “darkness, like an old friend” that threatens to take over the lightness and positivity he always seemed to be fighting for.