Walking into a locker room full of unfamiliar faces is one of the most uncomfortable aspects of youth sports. It’s a “going to school in your underwear” nightmare creeping into waking life, with the looming pressure of an athletic contest immediately following. Relating to a new group of teammates contributes to that discomfort: Some might not go to the same school as you, or their interest levels in the game that’s about to be played may vary from yours. In these situations, pop culture can be a great icebreaker.

When it came to locker-room lingua franca among hockey-playing kids in the ’90s, no language was more commonly spoken than that of The Mighty Ducks, an underdog-sports comedy that, after turning a tidy profit for The Walt Disney Company in 1992, inspired a pair of sequels, a tangentially related Saturday-morning cartoon, and, most impressively, a National Hockey League franchise, The Mighty Ducks of Anaheim.

As a Sports Illustrated For Kids subscriber with a fondness for the broad slapstick of the Home Alone films, The Mighty Ducks was right in my wheelhouse. I wasn’t alone in this respect among hockey-loving friends, but as we grew older and started playing recreation-league hockey ourselves, the conversation around The Mighty Ducks, D2, and D3 began to shift. Fart jokes that were once gut-busting favorites now seemed corny. Previously thrilling acts of on-ice derring-do looked downright hokey—and you’d probably receive a game misconduct just for trying them. No male teenager in his right mind would ever play air guitar on his hockey stick like Ducks bruiser Dean Portman. Several years later, Michael Showalter’s Wet Hot American Summer character would deliver a more pointed criticism of The Mighty Ducks and its ilk than anything conjured on the benches of the Metro Detroit area’s various hockey sheds:

“Yes, we’ve put together a motley crew you’d never think would be able to win a single game. We had a kooky training period where it seemed like—well it seemed like nothing was going to go right, but guys, somehow we made it to the finals. So I say, when those anonymously evil campers from Tiger Claw get here, we give it our best shot, then we try to come from behind at the last minute with some weird trick play that we’ve made up, and we win the game!”

At best, the adolescent urge to disdain any and all things sincere had a hold on us. At worst, we’d discovered the caustic rush of ironic appreciation, and it wasn’t long before my hockey buddies and I would watch D2 to laugh at the stilted line deliveries from cameoing NHLers or count the number of times the film’s villains—despicable goons representing that feared and respected hockey superpower, Iceland—should’ve been called for roughing.

We weren’t completely out of line: The three films that compose the Mighty Ducks franchise aren’t great pieces of filmmaking. But our initial enthusiasm for wasn’t entirely misplaced, either. The trilogy’s proudest achievement rests in putting a marginalized sport on the big screen—and putting the skates on kids, rather than adults. The generalities of the original Mighty Ducks are familiar—a ragtag group of kids pulls it together and wins big while having fun—but the specifics are unique. For kids in the ’90s, the only avenues to seeing hockey on film or home-video were cool parents (the kind that thought nothing of exposing young minds to the on-ice anarchy of Slap Shot) or VHS compilations like Don Cherry’s Rock ’Em Sock ’Em Hockey, an annual collection of the NHL’s greatest hits (and goals and saves) hosted by curmudgeonly coach-turned-commentator Don Cherry. Like the team it depicts, The Mighty Ducks welcomed hockey-loving kids who weren’t welcomed anywhere else.

It helps that the Ducks roster is filled out by a multitude of familiar stock types. Characters like Lester Averman (The Wiseass), Adam Banks (The Poor Little Rich Boy), Connie Moreau (The Girl), and Guy Germaine (The Taciturn French-Canadian) begin the series as lovable, one-note scamps whose few defining traits are repeated ad nauseam in the service of jokes and (limited) character development. Sure, there’s a cartoonish appeal in that repetition that speaks to young moviegoers, but there’s also a familiarity to the way the core Ducks are portrayed. We played with kids like goaltender Greg Goldberg, a coward who talked a big game and whose last name, invoked with friendly disdain, functioned as a team in-joke. We rode the bus with gentle giants like Fulton Reed, or had no-nonsense, protective older brother like Jesse Hall. And, like fellow ’90s everykid Cory Matthews, there was a little bit of Joshua Jackson’s Charlie Conway in all of us—though his bungled characterization as “Spazway” in the first film of the series made that an unattractive quality.

That relatability is lost as the franchise soldiers forward. An ensemble as large as the first film’s was bound to sacrifice lesser players to the sequel gods, but in replacing the likes of Peter and Karp (and, most unfortunately, figure-skating siblings Tammy and Tommy Duncan—then again, Danny Tamberelli had bigger blowholes to fry elsewhere), D2 introduces a colorful supporting cast of characters that aren’t stock types, but easily deployable gimmicks for gameplay sequences. The players they replace might not be missed, but characters like Southern-fried hot dog Dwayne Robertson offer even less to latch on to. D3 attempts to put a personality beneath Dwayne’s 10-gallon hat, but the script overcompensates, retconning the Texan export as the good-natured simpleton who could only be admitted to the tony Eden Hall Academy on a sports scholarship.

Nonetheless, it’s that untethering from previously established reality that made D2 such a prime My First Ironic Appreciation candidate; it’s also what makes the sequel the most out-and-out entertaining entry in the series 18 years later. D2 (if the riff on the promotional abbreviation for Terminator 2 wasn’t stale in 1994, it certainly is in 2012) conforms to the basic rules of film sequels: Take everything that worked about the first film and blow it up to epic proportions. Tammy may have been able to pull a triple axel in full pads and a helmet, but Kenny Wu does so with an Olympic pedigree.

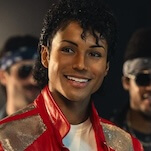

In D2, the Ducks aren’t just competing to be the best youth-hockey team in Minnesota—they’re playing for international bragging rights. Having triumphed over a philosophical adversary and embodiment of paternal disappointment (played by the decade’s own embodiment of paternal disappointment, Lane Smith), Emilio Estevez’s Gordon Bombay must now humble one-time NHL enforcer and Nordic Übermensch Wolf “The Dentist” Stansson. Despite concessions to themes of loyalty, greed, and the importance of staying grounded, D2 fully embraces its campiness, building on, say, the Toontown physics of Fulton’s slap shot with the gravity-defying “Knucklepuck,” the signature of trash-talking new recruit Russ Tyler (played by SNL’s Kenan Thompson in his first onscreen role). Not that D2’s lack of verisimilitude stopped me and everyone with whom I ever played hockey from attempting to reproduce the Knucklepuck in our driveways or during warmups. Russ claims his invention “drives goalies crazy”; in reality, the shot was the bane of every humorless coach’s existence.

Or maybe those coaches were just sore about the way their counterparts behave in the Mighty Ducks universe. The most frequent adult presence in these films carries a clipboard and a whistle, and since it’s not the scripts’ wont to make room for nuanced characterization, these authority figures mostly fall on opposite ends of the “Bombay vs. The World” spectrum. If you’re coaching hockey in a Mighty Ducks movie, you’re either an unrelenting hard-ass or a recovering hard-ass who rediscovers his love for the game by tying his goalie to the posts or conducts passing drills with a dozen eggs. The exception to this rule is D3’s Ted Orion, a former pro like Stansson who enters the film all bluster and emphasis on strong defense, before being humanized by a stirring pep talk and one of Estevez’s periodic pop-ins. (In order to maintain the illusion that the Junior Goodwill Games was an actual companion to Ted Turner’s alternate Olympiad and not an invention of D2, Bombay is removed from the bulk of D3 to take a job with the totally real Junior Goodwill committee.) Kid-centric sports movies tend to depict the grown-ups at their edges as bottomless wells of corruption; with the exception of the characters who guide our heroes, The Mighty Ducks movies toe that line as well.

In the grand tradition of the cable network that would make stars of Thompson and Tamberelli, the Ducks best the big, bad, jaded adults through ingenuity, enthusiasm, and strategically placed dog shit. The Mighty Ducks movies are imbued with the same prankster spirit that powered much of what Nickelodeon was turning out at the time, delivering characters who were not only relatable and (eventually) athletically gifted, but at a captivating advantage over most of the authority figures in their lives. Charlie and friends may represent a small geographic chunk of Minneapolis-St. Paul, but the real home team they’re playing for is kids everywhere. That’s why the “quack, quack, quack” chant rallies spirits as well in the classroom as it does on the ice.

To the members of the film’s target audience, Bombay’s squad are kith and kin to the casts of The Adventures Of Pete And Pete or Salute Your Shorts; with additional years of pop-culture knowledge and perspective on prior sports films and snobs-versus-slobs comedies, it’s clear the Ducks are also the successors to the Our Gang kids, as well as the dark-horse protagonists of Meatballs and The Bad News Bears. And when you’re paying your own rent, electricity bill, and digital-cable package with the NHL Network, it becomes clear that the Ducks’ disadvantages, like those of Camp North Star and the Bears, are tied to real-world, adult concerns like money and social class.

Playing organized hockey is wildly cost-prohibitive; before line items like registration fees and rink rental are factored in, there’s a laundry list of expensive equipment to purchase. Thematically, this is the strongest stuff of the trilogy, transcending the pratfalls and mid-game gimmicks. From a filmmaking and storytelling standpoint, it’s potent material that’s clumsily handled: In The Mighty Ducks, Bombay secures a sponsorship from his law firm by painting a maudlin picture of the kids suiting up in newspaper shin guards (reiterating an image the film has already displayed); D3 never passes up an opportunity for Russ to remind his teammates that they’re on scholarship, and if they lose those scholarships, they lose the Ducks, because the scholarships are the only things keeping the Ducks together. (Scholarship.) To sell these complicated issues to the kids, Steven Brill’s Mighty Ducks script introduces a catchy, regional “us vs. them” pejorative: “cake-eater,” a distillation of the most famous quote Marie Antoinette never uttered, which, in the youth-hockey leagues of Southeastern Michigan, eventually mutated into a catch-all insult for any opposing player.

In that regard, it’s perfectly logical that the term would outlast fond feelings for the films that popularized it. The message that The Mighty Ducks franchise broadcasts to adolescents and adults alike is one of loyalty, of sticking by your team no matter what. One of the goofiest conventions of the sequels involves the Ducks gathering under a new banner (Team USA in D2, the Eden Hall Warriors in D3) before charming and quacking their way back to their original team name in the third act. (The recurring “But we’re Ducks!” arc prompts plenty of petulance from Charlie in the final film of the trilogy; consider it training for his future angst benders on Dawson’s Creek, which launched two years after the release of D3.)

Eventually, like my and my teammates’ appreciation for The Mighty Ducks, the films’ use of “cake eater” turns ironic, morphing into a term of endearment for Adam Banks, an outsider who earns his Duck wings by being hated by the villainous Hawks as much as any other member of the team formerly known as District 5. And that’s what I’m getting at any time I send an instant-message non sequitur like “Wu, Wu, Wu, Kenny Wu!” to my younger brother—it’s not to mock these films, but to express our belonging to a club that spent too much of its teen years pondering the real-world efficacy of the Flying V. To quote D2, “When the wind blows hard and the sky is black, Ducks fly together.” And when a beloved pop-culture object curdles over time, but nonetheless provides a common ground for the people who once loved it, Mighty Ducks fans fly together.