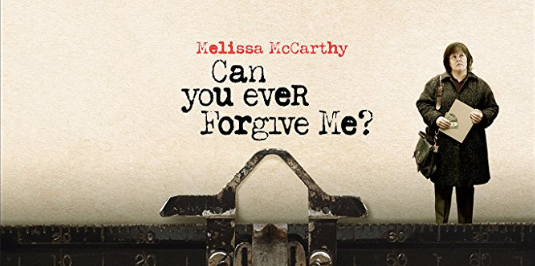

Can You Ever Forgive Me? finally gives Melissa McCarthy the dramatic vehicle she deserves

Yes, Melissa McCarthy was great in Bridesmaids. But ever since, she’s been stuck in a uniquely Hollywood purgatory: She’s a well-paid movie star who regularly top-lines films that open in the top 10 at the domestic box office. But she’s not the highest-paid movie star either, and her films rarely receive accolades. (Her last attempt at more serious fare, 2014’s St. Vincent, garnered a few nominations but no big wins.) McCarthy is a steady workhorse in an industry that prizes mercurial show ponies. And while she’s famous now, the spotlight is never guaranteed—especially not for women over the age of 40.

Lee Israel, the author McCarthy empathetically portrays in Marielle Heller’s intimate new biopic Can You Ever Forgive Me?, is living a cautionary tale of which many women, not just famous actresses, are very aware. A New York Times-bestselling celebrity biographer in the late ’70s and early ’80s, Lee refused to conform to societal expectations for a female author. By 1991, when the film opens, that refusal has torpedoed her career. “Oh, to be a white man who doesn’t even know he’s full of crap,” Lee sighs with teary-eyed frustration when her agent, Marjorie (Jane Curtin), informs her that not only is no one interested in the subject of her newest book, but no one is interested in Lee Israel either. Sitting alone at a bar in the middle of the day in a bulky sweater and asexual haircut, Lee might as well be invisible. And if you’re already invisible, why not turn to crime?

Specifically, Israel turned to literary forgeries, an esoteric form of lawlessness that nevertheless made her the subject of an extensive FBI investigation. In real life, as in the film, Israel turned to forgery out of desperation, adding a fake, juicy postscript to a real letter from vaudeville comedienne Fanny Brice in order to boost its selling price. Then she realized that she was quite good at faking letters from famous authors, channeling her wit and knowledge of history into convincing missives from the likes of “Dorothy Parker” and “Noël Coward” composed on vintage typewriters. (Much to the real Israel’s amusement, two of her forgeries even made it into a 2007 Coward biography.) But, as they tend to do, ego and alcohol got in the way.

The facts of Israel’s story are already out there for anyone who wants to learn them, a factor biopic directors always have to contend with. In this case, combined with the understated nature of Israel’s crimes, it makes for a film whose dramatic stakes are relatively low. But Heller, who made her debut with the coming-of-age drama The Diary Of A Teenage Girl, doesn’t try to artificially inflate them. Instead, she leans in to the understatement with a straightforward, character-driven narrative, propelled by Nicole Holofcener and Jeff Whitty’s script (and the occasional montage). The world-building, a requiem for threadbare ’90s NYC bohemia, is similarly low-key, as are the film’s LGBTQ themes.

This approach puts a lot of the focus on McCarthy’s performance as Lee, a character she inhabits as comfortably as a pair of sensible walking shoes. Key to McCarthy’s work here is the way she buries, but doesn’t suffocate, the brassy charisma of her straight comedic roles under Lee’s misanthropic exterior. Its spark ignites in her scenes with Richard E. Grant, who’s perfectly cast as Lee’s only real friend, alcoholic petty criminal Jack Hock. Grant’s crocodile smile adds an infectious sense of mischief to the film, and the duo’s chemistry is so good that scenes of them drunkenly gallivanting across Manhattan could fill an hour and 46 minutes all on their own.

Distilled to its most basic elements, Can You Ever Forgive Me? is about the criminal exploits of a middle-aged cat lady, and it’s as modest as that description makes it sound. But it’s also a film about dignity, and about a stubbornly independent person being forced to admit—very much against her will, by the way—that she needs other people sometimes, too. Maintaining an audience’s sympathy for a character through their most fumbling, frustrating lows requires compassion and clarity of purpose, both of which McCarthy amply demonstrates here. It’s a career-best performance, the kind of nuanced turn we all suspected she could deliver, if only someone would give her a chance to do it.