Cannes got radical in 1969, awarding violent teenage rebellion top honors

If…. (1968)

“True terror,” wrote Kurt Vonnegut, “is to wake up one morning and discover that your high school class is running the country.” The British filmmaker Lindsay Anderson would have agreed, judging from his 1968 down-with-authority screed If…. Kindred spirits in savage satire, Vonnegut and Anderson both understood school as a type of social incubator. What the educational system really teaches is the basic rules and hierarchies of adult life—a scary thought indeed for those convinced that graduating is an escape from the brutal classroom, not simply a passage into a much larger version of it.

Set at a boarding school where the upperclassmen reign with iron fists, If…. casts its stifling academic environment as a microcosm for the entire British Empire. When the film erupts into violence in its homestretch with its outcast underdog heroes waging war on their teachers and classmates, viewers are meant to take this insurgency as an expression of general anti-establishment sentiment. It’s a film, in other words, about tearing everything down; the bullies of secondary education are just easy stand-ins for all oppressors.

Yet real life, the non-vacuum in which films are made and released into, provided a different context. If…. opened in the U.K. in December 1968, mere months after a series of student riots rocked the foundation of French society. As a result, scenes of young rabble-rousers violently clashing with buttoned-up fascists took on a new relevance. Of course, in the case of cinema, timeliness is often a happy accident. Moviemaking moves slow, the full gestation from raw idea to final cut usually occurring over at least a couple of years. If…. was conceived as early as 1960, when it went by the tentative title Crusaders; Anderson finally began filming in spring of ’68, a few short weeks before the demonstrations began in Paris. The question is whether the filmmakers simply got lucky, the world providing their allegorical scenario with surprise significance, or whether they had their fingers on the quickening pulse of an angry Europe. Did they anticipate the chaos to come or simply benefit from it, thematically speaking?

Either way, If…. looks fundamentally like a product of its time, immortalizing a spirit of dissent that was sweeping across Western civilization at the end of the ’60s. At Cannes, the film must have looked like a preordained winner. A year earlier, organizers had canceled the festival midway through, as both a show of solidarity with the protestors and an acknowledgement that something bigger than a mere film festival was happening in France that May. (New Wave figureheads Jean-Luc Godard and Francois Truffaut were among those leading the charge to call off the event.) If…. was the perfect choice to commemorate everything that had happened over the 12 months prior. At a festival that often strives to honor “important” achievements, how could the jury—led by Italian director Luchino Visconti—not hand the top prize to a movie that seemed so essentially contemporary, like a transmission from the culture-war frontlines?

Anderson was not, it should be noted, the only filmmaker at Cannes that year who seemed high on the fumes of resistance. Ådalen 31, a drama from Swedish director Bo Widerberg, used a real-life 1931 massacre of labor demonstrators to remind audiences of the bravery of fighting for workers’ rights. (It would be nominated for the Academy Award for Foreign Language Film, only to lose to another political picture and Cannes ’69 alum, Costa-Gavras’ Z.) And then there was Easy Rider, that most iconic of American counterculture films, providing proof that even Hollywood was falling under the influence of an outsider ethos.

But If…. was different. It really ruffled feathers, earning widespread condemnation in its country of origin—not just for exposing some of the hypocrisies of the educational system, but also for actively encouraging revolt. Potential investors recoiled in disgust from the script, one reportedly telling Anderson that it was the “most evil and perverted screenplay that I’ve ever read.” (The filmmaker, who often fought with the gatekeepers of the British film industry, eventually turned to American producers for funding.) The climactic scene of campus bloodshed was conveniently omitted from the scripts presented to the schools at which Anderson filmed, resulting in justifiable backlash. When the movie was selected to compete at Cannes, an ambassador called it “an insult to the British nation,” and demanded it be removed from the lineup—a hysterical decree that probably made the film seem more dangerous and hence even worthier of the prize that was bestowed upon it.

More than 40 years later, If…. can still make audiences squirm; no matter how symbolic it may be, the schoolyard violence of the ending inspires a whole new level of discomfort in a post-Columbine, post-Virginia Tech world. (Maybe Elephant, which won the Palme in 2003, should be considered a bookend companion.) Yet beyond its anarchic spirit and revolutionary slant, Anderson’s film may be more fascinating today as a lively inside look at its milieu—the boys-only British boarding school, a petri dish of resentments, predilections, and unchecked cruelty. Anderson is said to have taken inspiration from Jean Vigo’s controversial 1933 short “Zero For Conduct,” about a rebellion in a French boarding school. But he also drew extensively from his own experiences at Cheltenham College (where the film was primarily shot), modeling several characters on people he really knew. The results, while much too surreal to pass for memoir, certainly benefit from a touch of authenticity.

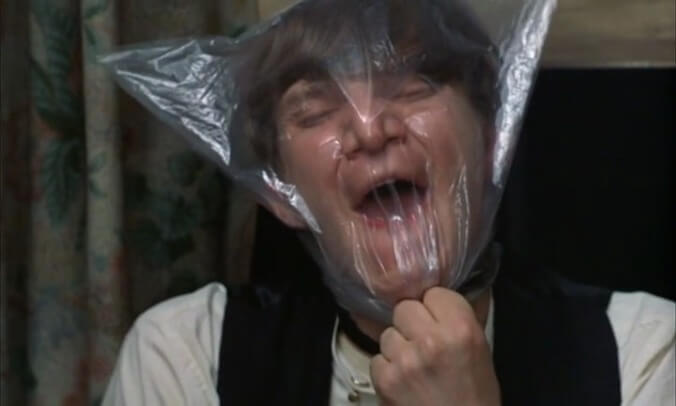

Divided into seven chapters, If…. doesn’t so much have a plot as a series of loosely arranged incidents, increasing in intensity en route to the final showdown. (Like many classic satires, it unfolds as a series of sometimes-comical vignettes.) The main characters are a trio of returning juniors, Mick (Malcolm McDowell), Wallace (Richard Warwick), and Johnny (David Wood). Back in boarding-school hell after a summer of freedom, the three bristle under the orders of their elders. While Peter Jeffrey’s headmaster puts a smiling, dignified public face on the institution, he has little day-to-day involvement in the discipline of the students. That responsibility is delegated to a pack of spoiled, empowered seniors, the “Whips,” who submit their peers to cruel and unusual punishment—as when, for example, they demand that Mick stand naked under a cold shower for an extended period of time. They also subjugate underclassmen, forcing them to serve as “scums” (or personal servants); there’s a hint of predatory sexual behavior to the way the freshmen are bartered among the Whips, one of whom (Hugh Thomas) conceals his own desires behind a prudish, feigned contempt for the “homosexual flirtatiousness” of his fellow adolescent tyrants.

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)