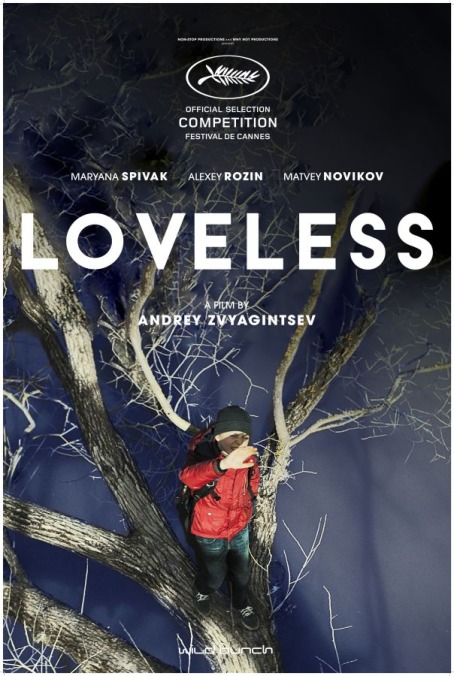

Cannes winner Loveless is a bracing reminder that things aren’t going great in Russia either

At a time when any mention of Russia on the news involves potential state-sponsored malfeasance, it’s useful to be reminded, courtesy of Russian cinema, that the country’s citizens have to deal with perfectly ordinary nightmares of their own. Andrey Zvyagintsev’s forbidding Loveless, which won the Jury Prize (basically third place) at Cannes earlier this year, tells the story of a singularly unhappy marriage, rooted in the sort of intense domestic detail more commonly associated with Scandinavia—Bergman, Strindberg, etc. Zhenya (Maryana Spivak) and Boris (Alexei Rozin) still live together, for the moment, but they’ve both long since checked out of the relationship, to the point where neither one bothers to hide the existence of their respective lovers. Every conversation, no matter how mundane, provides opportunities for petty sniping, which frequently escalates to near-murderous hatred. It’s not the healthiest environment imaginable for their sensitive 12-year-old son, Alyosha (Matvey Novikov), who spends most of his time either alone in his room, crying in front of the computer, or wandering the woods near the family home.

And then Alyosha disappears. For a while, it’s not clear whether his absence is literal or metaphorical, and Loveless packs the strongest punch during that remarkably lengthy early stretch, as the film alternately follows Zhenya and Boris planning their forthcoming new lives. Boris lolls in bed with his hugely pregnant girlfriend (Marina Vasilyeva), caressing her belly, anticipating another family entirely. Zhenya luxuriates in the lavish attentions of comparatively wealthy Anton (Andris Keiss). Neither of them seems to remember that they have a child, so overpowering is their need to escape each other—and, by extension, the human being that’s equal parts him and her. Alyosha, meanwhile, remains offscreen, unremarked upon, and as he keeps failing to reappear—without any suggestion that something has happened to him—it seems possible that Zvyagintsev is masterfully employing the kid as a form of negative space. What a bold conceptual move it would have been to represent the psychic damage that a toxic marriage inflicts on children by simply removing the child from the movie, with no explanation and neither of the parents ever noticing.

Zvyagintsev has something more conventional in mind, it turns out: family meltdown as allegory for national crisis. Multiple overheard news reports establish that Loveless is set in 2012, and pointedly mention events then happening in Ukraine; the film’s heavyhanded final shot makes it clear that Zhenya and Boris are meant to stand in for Russia itself, squandering its chance at fixing its problems. Still, it’s possible to overlook the blunt political subtext and appreciate the finely wrought drama that kicks in when two people who despise each other are united by concern over their child—who, it’s finally revealed, has indeed actually gone missing. Zvyagintsev—whose lugubrious 2007 film The Banishment pretty much banished all warmth from the theater—has loosened up a little in recent years, without remotely altering his bleak worldview. Leviathan (2014) pushed pitiless corruption into something like black comedy; Loveless is anything but funny, but does at least acknowledge fleeting moments of joy and understanding, even as it insists that they’re not nearly enough. Still, anyone who expects these warring parents to reconnect during the course of their desperate search needs to bone up on Russian cinema (or at least the subset of same that receives high-profile festival slots and U.S. distribution). It’s not all gleeful malicious hacking over there, any more than it is over here.