Cannes winner The Square is a scathingly funny art-world satire from the director of Force Majeure

Ruben Östlund is a maestro of discomfort, and The Square, which won the Palme D’Or at Cannes earlier this year, might just be his magnum opus: a two-and-a-half-hour cringe comedy about the foibles of supposed high society, unfolding as a daisy chain of exquisitely awkward episodes. Östlund’s last movie, the bleakly hilarious Force Majeure, established the Swedish writer-director as an authority on fragile male ego, following as it did a father and husband learning a hard lesson about his own protective instincts (or lack thereof). The Square, which dissects a very different species of flawed manhood, doesn’t have the same laser focus—it sprawls where that film pitilessly burrowed—but the scope of its ambition is perhaps equally remarkable. This is a movie with a lot on its mind, from art to altruism to the so-called bystander effect, and it could function as a Rorschach test for its audience, reflecting viewers’ anxieties and insecurities right back at them. It’s also just really, really funny, at least for those who can find humor in humiliation.

Östlund’s setting is behind the scenes of a contemporary art museum—an environment rife for parody. As the film begins, the museum is adding a new installation, one that encourages compassion and good-Samaritan behavior in passing observers; The Square, as it’s called, is really just some lighted tiles on the floor, but anyone within its borders can ask for whatever they need, under the idealistic assumption that those in proximity will help if they can. It’s the job of the head curator, Christian (Claes Bang), to enthusiastically introduce the project, and we see him practicing his speech in a bathroom mirror. Except it’s not just the prepared remarks he’s rehearsing, but also his “spontaneous” decision to diverge from them. His “from the heart” pivot off script is, in fact, scripted. It’s a brilliantly revealing character detail.

Christian, who drives a Tesla, donates to charity, and generally projects an air of enlightenment, turns out to be a carefully calibrated specimen of highbrow cluelessness, as precisely sketched as the crumbling family man of Force Majeure. He’s less an obvious blowhard than a cloistered faux intellectual, obsessed with presentation, whose values are more theoretical than lived. Östlund, in other words, is aiming his crosshairs at sham humanitarianism, and if that sounds like shooting fish in a barrel, the filmmaker keeps it sporting by resisting making his prey a total caricature. Like Östlund himself, Christian is also a divorcee with two daughters, and Bang, a Danish actor largely unknown in the States, lends a certain tragicomic shade to his slick pretension.

The Square spends most of its 150 minutes knocking its protagonist down a few pegs, through the domino effect of its various subplots. Early into the movie, Christian is a victim of an elaborate pickpocketing scam involving a woman who appears to be fleeing a man who’s trying to hurt her—one of many instances in The Square when the imperative to get involved in the plight of a stranger presents itself. Encouraged by one of his employees (Christopher Læssø) to take matters into his own hands, our hero embarks on an indiscriminate retaliation plan—a course of childish action that has unforeseen consequences for several parties. Östlund also makes room for an uncomfortable, almost screwball tryst between the curator and a journalist (a superbly passive-aggressive Elisabeth Moss). And Christian is so wrapped up in his personal life that he fails to monitor closely enough the publicity campaign being hatched for the new exhibit; through the hilariously misjudged results, The Square satirizes both outrage culture and the controversy-courting idiocy of viral marketing.

Because of his calculated formal prowess—the sometimes accusatory stasis of his compositions—and his interest in chipping away at the comfort zones of the bourgeoisie, Östlund has been compared to the reigning scold of European art cinema, Michael Haneke. The Square does bear some thematic resemblance to one of Haneke’s best movies, Code Unknown; both are interested in the idea of intervention—in why, why not, and when we choose to get involved in someone else’s problems. But if Haneke would rather croak than crack a joke, Östlund wraps his withering insights in impeccable farce, and he can execute a gag with steel-trap precision. The museum itself is an absurdist goldmine, facilitating jokes worthy of Jacques Tati; there’s a great punchline here involving an installation that’s just evenly constructed piles of stones, and another inspired bit involving an indignant dressing-down that’s interrupted (and undermined) by the offscreen clamor of some noisy art exhibit. And there are scenes of budget meetings and boardroom strategy sessions that almost play like direct spoofs of Frederick Wiseman’s documentary on the National Gallery.

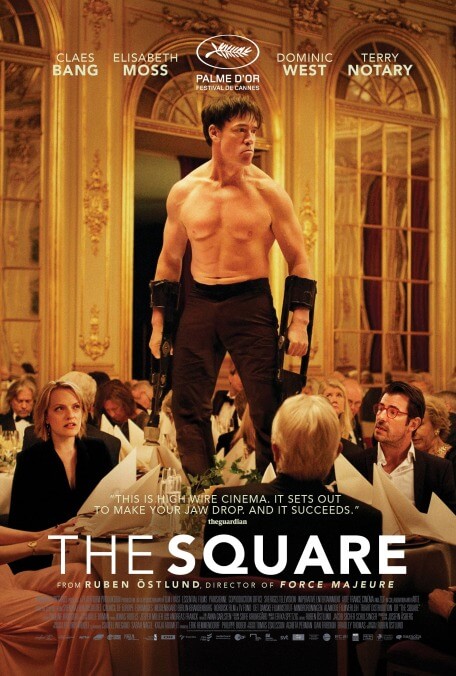

If nothing else, The Square works as a collection of great individual moments; one could waste a whole review just describing its most provocative or pointed episodes. The movie’s confrontational centerpiece—and maybe the scene of the year—concerns a performance-art stunt gone wrong, as several tables’ worth of wealthy donors, patrons, and aficionados, all seated for a black-tie dinner, are “entertained” by a shirtless actor (Terry Notary), gesticulating like a wild ape, stalking the dining hall, and harassing anyone who reacts too noticeably to his wandering-predator routine. As the aggression of the performance intensifies, from vaudeville shtick to outright antagonism (and uncomfortably beyond), laughter chills into a collective paralysis of stress. Art is more dangerous than these self-proclaimed art-lovers imagined it would be. They’re held hostage by it—and the movie, in hardwiring its entire audience to the anxiety of its characters, achieves a queasy forced identification.

Part of the disturbing power of the scene is waiting, on bated breath, for someone, for anyone, to step in and put a stop to what’s happening. (One could argue that it’s the point of the fictional performance, too.) Again and again, Östlund returns to this tricky question of social responsibility; the words “Help!” are uttered, to varying degrees of success, throughout the film, confronting Christian with the limits of his empathy. But if The Square is scathing in its indictment of empty philanthropic gestures—of making and supporting art about helping others, but not really putting that philosophy into practice—it’s self-implicating, too. At one point, the museum’s dopey, exploitative PR team argues that the public really responds to images of the homeless. What does it say that The Square employs that very strategy, using vagrants as visual evidence of his characters’ blinkered indifference? It’s worth noting, too, that Östlund launched a real version of The Square a few years ago; maybe Christian is more auto-critique than straw man. The Square holds a mirror up to its audience, but it catches its creator in the reflection, too.