Ben Cash (Viggo Mortensen) doesn’t just live his values. He passes them on to his children like a gospel, molding their minds and bodies to his perfect ideal. Deep within the wilderness of the Pacific Northwest, the man raises a small brood of self-sufficient, socially conscious brainiacs—six kids, ages 7 to 18, roughing it off the grid like a countercultural Swiss Family Robinson. They hunt and grow their own food. They rely on little modern technology. And they adhere to rigorous regimens of physical and intellectual exercise, scaling treacherous bluffs before lunch and getting a crash course in science, politics, philosophy, and literature afterward. To Ben, this secluded incubator—and the extreme homeschooling practiced within it—is a paradise on Earth. To those outside his bubble, it can look at best like a form of child abuse, at worse like a cult: the nuclear family as survivalist militia.

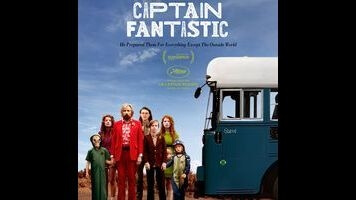

But audiences weaned on a certain strain of festival favorite, the kind brought of age in the charitable hype chamber of Sundance, will see something cuddlier and more familiar in the Cash family. What are Ben and his offspring really but the latest in a long line of lovable misfits too free-spirited to be tamed by “normal” society? Captain Fantastic comes on like a portrait of life on the fringe, set in a backwoods boot camp for perfect citizens in training. Then the bad news arrives: Leslie (Trin Miller), the bipolar matriarch of this unusual clan, has lost her battle with depression, taking her own life in an institution. Ben, a newly single parent, packs his half dozen charges into a van and heads south to New Mexico for his wife’s funeral, despite strict instructions from her resentful parents to stay far, far away. Tragedy leads paradoxically to comedy, and suddenly Captain Fantastic is conforming to the crowd-pleasing template of a road movie, as Ben’s principles clash with the plugged-in culture encountered en route. Little Miss Sunshine has some new company in the carpool lane.

Mortensen’s efforts here are downright heroic. It’s hard to imagine anyone better in this role, for bringing out the authenticity in a character teetering on the precipice of caricature. Ben, a self-made anachronism, is a perfect fit for an actor who excels at playing mythic loners of the distant past; Mortensen seems most at home when plopped into any era but his own—a quality that also makes him qualified to embody a luddite, carving out his own reality on the edge of civilization. He’s not afraid to make the guy complicated, even occasionally unsympathetic: With an unkempt forest of facial hair, Mortensen looks a little like Charles Manson, and there’s certainly a touch of cultish intensity to the character’s worldview, the way he sees everyone who’s not hip to his analog lifestyle through a tunnel of moral superiority. But Ben isn’t quite humorless; Mortensen reveals little cracks of levity in his tough-love parenting style—a gentle tinkle of self-awareness.

He’s definitely more well-rounded, more adaptable than his gaggle of trivia-spouting munchkin prodigies, who are like miniature versions of the most self-possessed graduate student you’ve ever met. To his credit, writer-director Matt Ross, who’s better-known as an actor (he’s delectably villainous as Gavin Belson on Silicon Valley), sometimes challenges his protagonist’s utopian ideals as well as the effect they have on his hopelessly sheltered spawn. The movie makes a pit stop at the suburban home of Ben’s sister (Kathryn Hahn) and her husband (Steve Zahn), mostly for the purpose of allowing the two to raise serious questions about how he’s preparing his kids for the “real” world. Likewise, Ross casts Frank Langella and Ann Dowd as the grieving, disapproving in-laws, which is a pretty good way to make the objections sound sensible. Captain Fantastic is at its best, in other words, when creating a dialogue about parenting. Ben clearly gave up a whole other life for fatherhood, but is his grand experiment in child-rearing really just an excuse to withdraw from the world? Isn’t he just programming his kids, too, the way every parent imprints their own values on their young?

Captain Fantastic flirts with seriously dissecting Ben’s methods and philosophies, only to pull the cinematic equivalent of that old high-school term-paper trick: address the opposing viewpoint, then double down on the “right” one. Ross stacks the deck heavily, painting the nieces and nephews as brain-dead electronics junkies, before letting freak flags fly in the severely sentimental backstretch, capped by a family-band sing-along of “Sweet Child O’ Mine.” Mostly, however, Ben’s whole alternative life plan is just a pretext for lightly amusing fish-out-of-water comedy, as Captain Fantastic scores easy laughs from a pint-sized tyke throwing around five-dollar expressions like “fascist capitalism,” the eldest son (George MacKay) coming on too strong during a fledgling stab at romance, and the whole family shoplifting from a grocery store to properly celebrate Noam Chomsky Day. (“But Noam’s birthday isn’t until December 7,” one of the annoyingly precocious kids protests.) That Ross treats the death of a loved one as little more than a plot catalyst—a way to get everyone on the road—is in keeping with the tidy manner in which his film sorts through messy material. Were these wunderkinds real, they’d surely detect the irony: A film about thinking (and living) outside the box fits snugly into it.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.