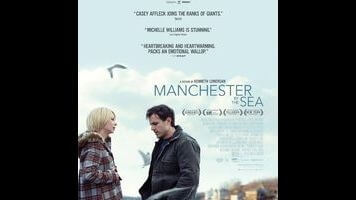

Casey Affleck has a hard homecoming in the masterful, moving Manchester By The Sea

Somewhere around the midway mark of his magnificent new movie, Manchester By The Sea, writer-director Kenneth Lonergan stages a small moment of wordless frustration that speaks volumes. A woman, coughing and sobbing, is being wheeled into an ambulance on a gurney. Her whole world has been shattered; this is, without question, the worst thing that’s ever happened to her. But on top of all she’s going through, a petty inconvenience asserts itself: The paramedics can’t seem to get the gurney to cooperate—it keeps getting stuck as they try to safely, gently lift it into the vehicle. The universe, Lonergan slyly suggests, will not accommodate your personal crisis. At your lowest point, it will still hit you with ordinary irritations, the small stuff you sweat when you’re not coping with the big stuff. Furthermore, the people available in your darkest hour to help you through it may not be perfect at the job. Literally or figuratively, they may have trouble with the gurney.

Manchester By The Sea sweats the big stuff and the small stuff, and that’s key to its anomalous power: This is a staggering American drama, almost operatic in the heartbreak it chronicles, that’s also attuned to everyday headaches, like forgetting where the car is parked and hitting your noggin on the freezer door. Lonergan has had troubles of his own; his last movie, Margaret, suffered a litany of setbacks, disappearing into the editing room for years. Getting another tough, complicated character study off the ground after the well-publicized difficulties of that one is an accomplishment in and of itself. But for his third feature, the playwright-turned-filmmaker hasn’t retreated from Margaret’s messy ambition. Instead he’s managed, somehow, to wed it to the emotional intimacy of his acclaimed debut, You Can Count On Me. The results are almost unspeakably moving—and, at times, disarmingly funny.

Casey Affleck, in the great internal performance of his career, plays Lee Chandler, a withdrawn handyman scraping by in Quincy, a suburb of Boston. Lee is the kind of miserable bastard who’d rather sucker-punch a stranger at the bar than go home with the beautiful woman trying to pick him up. Who is this broken man? What eats at his heart and swims behind his eyes? The questions hang like storm clouds over the early scenes, a solitary life told in odd jobs and punchlines: Lee shoveling snow, Lee screwing in a lightbulb, Lee unclogging a toilet for a tenant who has the hots for him. Frances Ha editor Jennifer Lame gives this opening passage a certain comic pop, until a phone call sends Lee racing to his hometown of Manchester By The Sea—but not fast enough to say goodbye to his older brother, Joe (Kyle Chandler), who’s just died of the degenerative heart condition he’s been afflicted with for years. Lonergan, ever fascinated with the vagaries of social interaction, lets the hospital conversation play out in its awkward entirety, soaking in both the sadness and the sign-here formality.

The obligation, the strange business, of attending to a deceased relative’s affairs drives much of Manchester By The Sea. As if the grief weren’t enough, Lee also has to make arrangements with the funeral parlor, decide whether to keep the body on ice (the ground is too cold to bury him in the winter), and figure out what to do with the cherished family boat, which no one can really afford to maintain. But his biggest concern of many is the looming responsibility of guardianship: Joe’s son is now 16-year-old Patrick (Lucas Hedges, a naturalistic star in the making), and Joe stipulates clearly in his will that he wants his surviving brother to take custody. But is this closed-off man up to the task? “I was just a back-up,” Lee insists to the lawyer.

Part of the problem is the town itself, site of some very bad memories for Lee. Lonergan applies a sophisticated flashback structure, fleshing out his characters’ relationships and slowly meting out crucial information about their backstories. The film opens on Massachusetts water, watching from a safe distance as a younger, happier Lee and a pint-sized Patrick josh around on a fishing boat. It’s a poignant image the writer-director will return to again and again, like waves crashing into land. We also meet Lee’s ex-wife, Randi (Michelle Williams, typically lacerating in a small number of scenes), as well as Joe’s wife, Elise (Gretchen Mol). A great tragedy lurks in this family’s past, one Lonergan treats as worthy of The Met—note the sweeping classical compositions of George Frideric Handel—but with the same accumulation of piercing, mundane detail that defines the present-day material.

Better than most Hollywood stars at evincing a genuine just-one-of-the-boys quality, Affleck has been terrific before, playing the craven turncoat of The Assassination Of Jesse James By The Coward Robert Ford or the Dorchester sleuth of his older brother’s directorial debut, Gone Baby Gone. But the actor has never burrowed as deep as he does in Manchester By The Sea, a drama that entrusts him with the herculean task of making perpetual numbness compelling. The flashbacks help, allowing Affleck to layer his performance, showing us the gregarious knucklehead Lee once was, before mistakes hollowed him out into a shell of his former self. But even with Lonergan supplying whip-smart dialogue, this is a movie that could only work with a leading man capable of creating emotional walls and giving us peeks of what’s on the other side of them. Affleck comes through, like the slivers of personality—of warmth, of anguish, of sarcasm—streaming out of the cracks in Lee’s emotional armor.

He also has an exceptional scene partner in Hedges, who never conforms Patrick—a “jock” both popular and sensitive—to any particular clique. Manchester By The Sea, like Margaret, understands that even the trauma of a recent death wouldn’t entirely dominate a teenager’s attention. Patrick plays hockey for his high school team, plays guitar in a (refreshingly, believably mediocre) basement band, and juggles two squeezes, one of whom he spends long stretches of the movie amusingly attempting to get alone. In other words, Patrick has a full, fulfilling social life—something he throws in the face of the surrogate parent threatening to drag him off to Boston. There’s a lot of humor in their collisions: The two have a contentious rapport, bickering and talking over each other (not since Robert Altman has a filmmaker made better use of overlapping dialogue), and Lonergan turns the repeated shot of Lee driving over a bridge to begrudgingly drop off or pick up Patrick into a running visual gag.

But the heart of Manchester By The Sea is also this same relationship between uncle and nephew, forged in that opening scene on the boat, complicated by estrangement, and transformed by a mutual grief neither seems capable of fully articulating. This is a particularly regional story of mourning and male bonding, and not just because Lonergan makes his gorgeous seaside setting—captured through precise details of language, culture, and punishing weather—as important as his native New York was to Margaret. Lee and Patrick, fiercely loyal Irish Catholics who refuse to wear their deep feelings on their sleeves, connect the film to a storied tradition of Massachusetts movies about guarded men connecting through their defense mechanisms. Their unsentimental sentimentalism keeps Manchester By The Sea in a near-constant state of heightened emotion, while helping it sidestep the obvious cathartic choice at every turn. Lonergan, for example, sets the scene where Lee breaks the bad news to Patrick at a hockey practice, staging it from the distant perspective of the kid’s teammates on the other end of the rink. Life isn’t simple, so neither is the drama.

Are there experiences so crushing that they ruin you forever? That’s the big question Lonergan asks, and we wait hopefully for a charitable answer. The filmmaker doesn’t need manipulative tricks to wring us dry. Heartache rips through his movie like a stiff coastal breeze, and there are moments—such as a reunion of unexpected vulnerability between Lee and Randi—that quake with feelings so intense they could destroy just about any viewer’s composure. But Manchester By The Sea is also alive with character, with the rich, funny, and complex people Lonergan puts up on screen and the pages of prickly, combative conversation he gifts them. Watching feels like nothing less than being pulled into the lives of this damaged family, grappling with the big stuff, the small stuff, and everything in between. It’s why we go to movies. Or it should be, anyway.