Every once in a while, the real world delivers a barn burner so dramatic that it would get dinged as pure contrivance if a screenwriter invented it. For the game of tennis, that magic moment arrived at Wimbledon in 1980, with the final match of the Men’s Singles championship. On one side of the net was Björn Borg, Swedish world No. 1 superstar, chasing a record-breaking fifth consecutive win at the tournament. On the other side was his fiercest competition, brash New York underdog John McEnroe, then ranked second. Borg was the consummate professional and “gentleman,” admired for his unflappability on and off the court, feared for his almost mechanical resolve and talent. McEnroe was the controversial hothead, widely detested for his habit of constantly losing his temper and cursing at spectators. In both style of play and temperament, they were near opposites, which only fueled the media frenzy around their impending face-off.

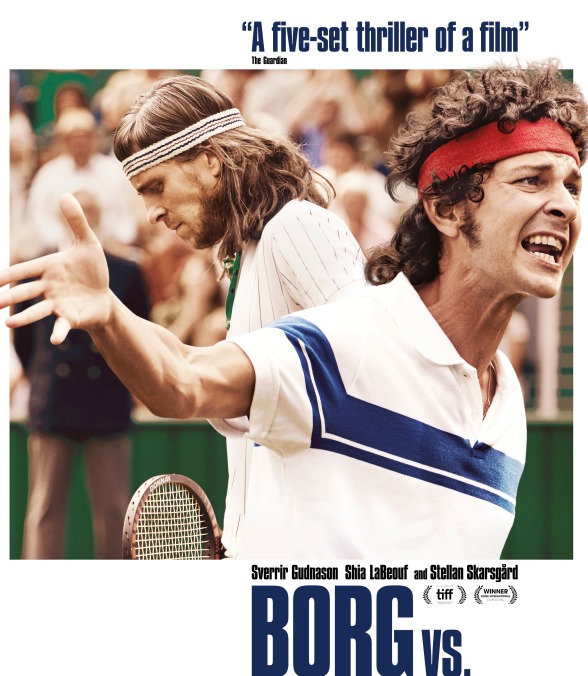

Remarkably, the event itself lived up to the hype, tensely seesawing between the two men, then crescendoing with a 20-minute tiebreaker in the fourth set. Today, it’s frequently cited as the greatest match in the history of tennis. But great games don’t always make for great movies, and the irony of Borg Vs. McEnroe, starring Swedish actor Sverrir Gudnason as the former and Shia LaBeouf as the latter, is that it makes a showdown that played out like the height of crowd-pleasing fiction—like Hollywood fantasy unfolding on live television—look like just another overwrought, underwhelming sports drama.

Beginning with a brief glimpse of its own climax, Borg Vs. McEnroe unfolds over the full fortnight of the tournament, tracing both men’s route to the final. Not for nothing is Borg referred to as The Iceman; a slave to his superstitious routines, he can be an enigma even to those closest to him, including the fiancé (Tuva Novotny) he keeps at arm’s length. McEnroe, meanwhile, leans into his bad reputation—turning press conferences into wars of words, lashing out at the crowds who boo him, playing antagonistic head games with his opponents. Casting LeBeouf, another troublemaking celebrity people love to hate, is the closest the film comes to a masterstroke. Like Lars Von Trier and Andrea Arnold before him, director Janus Metz harnesses Shia’s assholery instead of trying to disguise it. If nothing else, the parallels between role and performer give the McEnroe scenes an extra charge of verisimilitude.

Unlike the recent Battle Of The Sexes, which also dramatized a famous tennis match, Borg Vs. McEnroe doesn’t possess ideological stakes, unless one fervently believes that potty mouths have no place in the sport. And there’s not a lot of suspense until the end, even for the uninitiated, because the out-of-order opening scene blatantly establishes that Wimbledon will come down to these two contenders. The focus instead lands on the personalities of the players, and screenwriter Ronnie Sandahl’s working theory is (get this) that the two were more alike than different. Laborious origin-story flashbacks to Borg’s youth as a hotheaded prodigy indicate that his famous composure was something he carefully cultivated over time. (“Promise to never show a single bloody emotion ever again,” his trainer, played by Stellan Skarsgård, implausibly tells him.) Conversely, scenes behind closed hotel doors demonstrate how McEnroe’s short fuse was more strategy than impulse. But this two-sides-of-the-same-coin dichotomy is as deep as the psychology runs.

Assumedly aware that he’s making a movie about one of the less cinematic of sporting events, Metz (over)compensates with a lot of bombastic, jittery style: amplifying the crunch of flashbulbs to a roar, generally taking notes from Ron Howard’s addition to the famous-sports-rivalry genre, Rush. At least the tennis scenes themselves are dynamically staged; cutting on nearly every collision of ball and racket, they inflate the intensity of the game without turning the climactic match into an incomprehensible jumble. But it’s all part of the film’s aggrandizing but unspecific approach. “Every match is a life in miniature,” goes an opening Andre Agassi quote, and for as much as Borg Vs. McEnroe recognizes the neurosis of these two competitors—driven only by ambition, at the expense of their personal lives and/or reputations—it also comes close to depicting them as gladiators, towering tall in their arena of choice. Pity that Metz exhibits so little interest in delineating the play styles of the players, in capturing what made them the best. Borg Vs. McEnroe all but tells us that we’re seeing the greatest tennis match of all time. But it doesn’t show us.