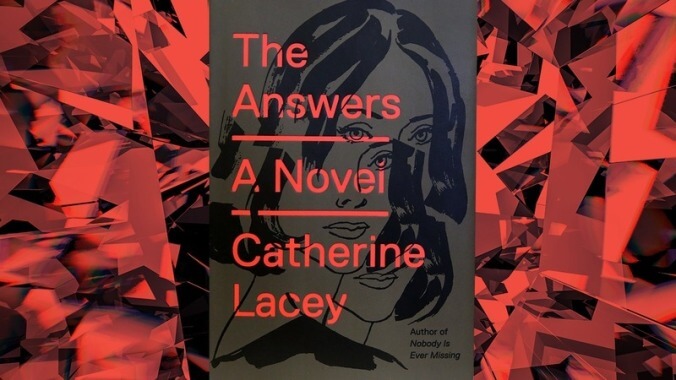

Graphic: Nicole Antonuccio

Sitting in a small, white room, a woman spies what she believes is a two-way mirror. “It depressed me to think that I might have been looking at another person but seeing only myself,” remarks Mary Parsons, the protagonist of Catherine Lacey’s complex and haunting second novel, The Answers. She is applying for a job in the Girlfriend Experiment, a project wherein a team of women will serve as girlfriends to one man, an egotistical New York actor-filmmaker named Kurt Sky, to help measure and maximize romantic love. There is, for example, an Anger Girlfriend, a Maternal Girlfriend, a Mundanity Girlfriend, and Mary’s eventual role, the Emotional Girlfriend. White-coated scientists track the participants’ biological signs and strictly regulate the Girlfriends’ behavior, including their eye contact and speech. In the sterile, satirical manner of Yorgos Lanthimos’ The Lobster, the novel considers whether love is merely a “willful manipulation” and presents this solipsistic idea: people looking for love only wind up finding themselves.

One theme running beneath all this is money and how vastly the lives of the haves and have-nots differ. Lacey expertly mocks rich, self-important urban dwellers like Kurt who contort themselves to spend money in ridiculous, ever more complicated ways. There’s a secret, menu-less bar whose “cocktail artist” creates drinks according to each patron’s supposed needs; a juice bar where ordering a plain water proves impossible; and, of course, the Girlfriend Experiment itself. While the wealthy use money to make their already very good lives even better, the poor or insolvent try merely to make their intolerable lives tolerable.

For her part, Mary becomes involved in the Girlfriend Experiment to pay for the prohibitively expensive treatment of her mysterious, debilitating ailment. The New Age-y and equally mysterious Pneuma Adaptive Kinesthesia (or PAKing) therapy she undergoes—think crystals and paired yoga in dark rooms—is performed by Ed, who alternately whispers hippie-dippie mumbo jumbo like “Our spirits know so much more than we can” and shares eerily accurate prophetic visions. These passages are reminiscent of the disquieting world of Paul Auster’s New York Trilogy, in that other characters somehow know more about the protagonist’s inner life than she does (“the sense of a subtext,” as Mary puts it), creating a foreboding gap in knowledge.

Lacey’s prose especially shines when describing the strange physical sensations Mary experiences during the PAKing sessions, though the author doesn’t display the same wild abandon in her writing here as she did in her Whiting Award-winning first novel, 2014’s peripatetic Nobody Is Ever Missing, which was full of long, winding sentences that tumbled forth with unrestrained verve. Those inclinations occasionally pop up here, but the screws are tightened in favor of plot; the novel’s abundant, penetrating thoughts on love and self; and in-depth characterization of even ancillary players: Kurt’s irascible personal assistant, Matheson; Mary’s spiritually attuned best friend, Chandra (so delightfully close to “chakra”); and the rage-filled Anger Girlfriend, who’s a boot knife to Mary’s limp noodle. The narration seamlessly traverses multiple perspectives, spending most of its time outside of Mary with Kurt, whose narcissistic lack of empathy verges on sociopathy. Mary’s main task as the Emotional Girlfriend is to actively listen to him and mirror his behavior, shepherding him toward a deeper understanding of himself.

With Mary, a self-described “homeschooled semi-orphan from a barely literate state,” Lacey has created another complex protagonist who has trouble functioning in what one might call normal society, or in the world at all; like both the Girlfriend Experiment and PAKing, Mary’s hermetic upbringing is another study in complicated becoming. Mary can’t perform an action, as small as holding her hands in her lap, without wondering if she should be doing something else, contradicting her thoughts with their opposite in each passing moment. “I keep wondering what, in me, might be constant,” she thinks when remembering her childhood. Lacey writes loneliness and solitude with a profound depth, injecting life into the anxious fluttering of those wondering, wandering individuals who just don’t know what to do with themselves and who can’t stop asking life’s most impenetrable questions. There’s a joke to be made about The Answers not offering up any, but the ideas it interrogates are so immense, and fundamentally existential, that any single explanation would ring false. “Such a serious thing we are doing, and no one really knows how to do it,” Mary says of love, the closest this probing novel comes to a sure conclusion.

Purchase The Answers

here, which helps support The A.V. Club.