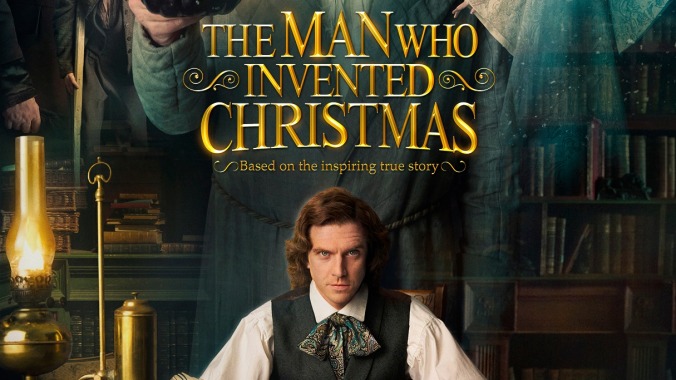

Charles Dickens gets his own superfluous origin story in The Man Who Invented Christmas

Movies about writers always struggle with the fact that the writing process is almost unfilmable; the manual work of scribbling and typing letters is only a small, visible part of it. But The Man Who Invented Christmas, which dramatizes the six weeks that it took a cash-strapped Charles Dickens (Dan Stevens) to pen A Christmas Carol, actually comes up with an effective way of visualizing a writer’s private, neurotic craft: It has the characters of the yuletide classic—Ebenezer Scrooge (Christopher Plummer), Tiny Tim, Fezziwig, and the rest—follow Dickens around, like ghosts invisible to everyone except the author, questioning his plot ideas and prodding his insecurities; at one point, he has to lock them into his study to get away.

We see a manic Dickens, stalked by his work and his feelings of inadequacy and failure. Padding the streets of London at night, he spots a bookstore sign hawking the still-unfinished book: “Order now and avoid disappointment!” The whole idea is flush with theatrical potential (the roles are even double-cast, à la The Wizard Of Oz), which is apt, given Dickens’ own comments on his creative process (he claimed his characters spoke to him) and the lifelong obsession with the stage that stemmed from his early days as a failed actor. It begs for stylized, scenery-moving outrageousness—something along the lines of the late Ken Russell, or at least Darkest Hour’s Joe Wright. Sadly, all it gets is the anonymously cloying, middlebrow direction of Bharat Nalluri (Miss Pettigrew Lives For A Day).

Adapted from a 2008 nonfiction book by Les Standiford, The Man Who Invented Christmas introduces Dickens in 1842, during his successful American tour—the star author of Oliver Twist, Nicholas Nickleby, and The Old Curiosity Shop ushered onstage with confetti and kicking dancers. A year and several flops later, the money has begun to run out; to add insult to injury, William Makepeace Thackeray (Miles Jupp), the original snob, won’t stop reciting pans of Dickens’ latest books from memory every time they run into each other at the Garrick Club. And so, with a fifth child on the way and Italian interior decorators to pay, the writer decides to dash off and self-publish a novella about Christmas—after, of course, being rejected by his publisher, whose dismissive comments about the holiday partly inspire the old cheapskate Scrooge.

Christmas’ script is by Susan Coyne, the co-creator of Slings And Arrows, and it follows the interpretation of Scrooge as Dickens’ alter-ego, his miserliness a caricature of the novelist’s preoccupation with money, which began when his opportunistic father, John Dickens (Jonathan Pryce), was sent to debtors’ prison, forcing a 12-year-old Charles to quit school and go to work at a shoe polish factory. Thus, the redemption of Scrooge becomes a symbolic self-healing—and that’s where the film gets itself stuck in a mess of semi-fictionalized biographical and intentional fallacies. Christmas has some good points going for it (e.g., Plummer’s grumpy, rascally Scrooge, who’d be great in a straight adaptation), but its portrayal of Dickens’ biography and family life is resoundingly dull, apart from some tense notes in Pryce’s performance.

Ralph Fiennes’ The Invisible Woman—a much darker, glummer film than this one, about Dickens’ relationship with his mistress, the actress Nelly Ternan—at least made the writer a more human character than Stevens’ luxuriantly locked instrument of over-reaction. (Nothing against Stevens, but much of the role could have been performed by a cocker spaniel.) Too much of the film ends up riding on his swaying shoulders. Apparently writing the most popular Christmas story since the one with three wise men and the manger wasn’t enough—he has to learn to be a better man, too.