One would be hard-pressed to find a more perfect fantasy sequence in all of film than the Tramp’s dream of an ersatz heaven in The Kid, with wobbly angel wings that fleck feathers like dandruff and angel dogs who look around in confusion as they are flown away on hidden wires. The sequence, dreamt by Charlie Chaplin’s iconic vagrant as he sleeps on a skid-row stoop, is all the ending that The Kid needs, though the movie appends one anyway: a happy reunion, also staged in a doorway, albeit of an art deco mansion. This unnecessary final scene is the kind of closure that Chaplin would eventually do away with, preferring to end movies on upswells of emotion; it’s safe to say that an older Chaplin would have ended The Kid on the powerfully bittersweet note of the Tramp being roused from his dream, in which he could fly and everything was free, but he still somehow ended up getting chased by the local cop. Even in heaven, a bum can’t catch a break.

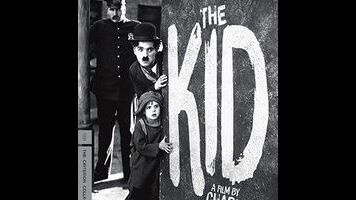

More importantly, The Kid finds Chaplin testing himself for the first time—not as a comedian, for he would make plenty of funnier movies, but as the most purely emotional of all filmmakers. In typical Chaplin style, the plot is a deeply personal mix of Victoriana and fairy tale: An unnamed woman (Edna Purviance), leaving the charity hospital as an unwed mother, hopes for a better life for her baby, and leaves him in a millionaire’s limousine, bundled with a note that reads, “Please love and care for this orphan child,” with a splotch of ink on the final down stroke of the n. Before she has time to change her mind, the car is stolen, and the baby is ditched in an alley, to be found by the Tramp. Five years later, the boy (Jackie Coogan, in one of the greatest and most energetic performances every given by a child actor) is the Tramp’s adopted son and partner in petty crime, scamming locals by breaking their windows and then offering to fix them.

The rough qualities of Chaplin’s filmmaking are basically inseparable from what makes it genius. Like so many of his features, The Kid is packed front-to-back with continuity errors; if set down, the Tramp’s famous bamboo cane will regularly jump a foot between cuts. And yet, Chaplin was a perfectionist. He shot a ungodly amount of footage while making The Kid, though it was nothing compared to the two years of continuous filming that would produce City Lights. What was he after? Certainly not greater realism. For all their hard luck and everyman appeal, Chaplin’s mature films are deeply artificial. One of the most revealing extras on the new Criterion disc are the original inter-titles, which were set in a more modern-looking typeface (without old-timey illuminated capitals), and feature less archaic punctuation; revisiting the film in his 80s, Chaplin simplified the plot, cutting several scenes with Purviance’s character, but also deliberately made the movie seem more out-of-time.

Chaplin’s mature work doesn’t move like anyone else’s; it’s eccentric and usually episodic, fractured by most standards, with The Kid being one of the most conventional in terms of narrative. Chaplin was anything but a sloppy filmmaker; he was simply after something that mattered more than whether two eye-lines aligned in the final cut. And he was right. No director has ever had a better instinct at reaching and holding an emotional note, which is why his features, many of them otherworldly, haven’t aged at all. In The Kid, he invests his flair for perfect comic timing with sweetness—especially in regard to the relationship between the Tramp and the boy, much imitated by later films—and the sadness with a fleeting happy moment, which he would go on to do better than anyone else in the history of the medium. The film’s best gags are also its most poignant, like the flophouse scene in which the Tramp tries to hide the boy so that they can share a bed for a dime.

In its greatest moments, The Kid is a genuinely moving work by an artist in transition, still searching for his sweet spot between comedy and drama; his next feature would be the neglected A Woman Of Paris, the closest he would ever get to a pure drama, appearing only in a cameo. Perhaps because it’s the shortest movie in Criterion’s Chaplin catalogue, The Kid has been given one of the label’s more scholarly editions, with an essay by academic and all-around silent film booster Tom Gunning, archival interviews with cast members and collaborators, a biographical commentary track, and an extended video piece on undercranking, the pervasive silent-era practice of shooting movies at one frame rate to be projected at another. (Full disclosure: This writer contributed to one of Criterion’s earlier Chaplin releases.) There are plenty of other features: a video essay on Coogan; a newsreel (from the sublimely named Topical Budget) about Chaplin’s first time back in England after ascending to global stardom; an elaborate home movie made for the wedding of Lord Mountbatten. Most important, though, is a transfer that preserves the extremely fine grain of silent-era film stock.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.