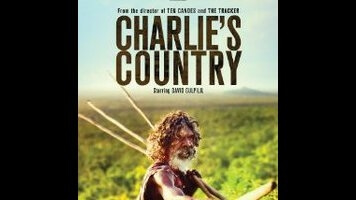

This air of independence gets put to superb use in Charlie’s Country, the new film from Rolf De Heer, who previously collaborated with Gulpilil on The Tracker and Ten Canoes. Gulpilil, who co-wrote the script with the director, stars as Charlie, a rascally, sixtysomething resident of an Aboriginal reserve in Australia’s Northern Territory. Like Ten Canoes—which was set in the same area, but before Western contact—the movie is distinguished by its graceful camera movement and fluid sense of narrative, sliding from one self-contained episode into another: Charlie goes hunting, Charlie steals a police car, Charlie decides to go back to the old ways, Charlie joins a community of homeless drunks, and so on and so forth.

It plays like a daily comic strip or a series of silent-era one-reelers, with Charlie sometimes joined by his buddy Black Pete (producer Peter Djigirr) or antagonized by clueless white policeman Luke (Luke Ford). What it adds up to is a broadly drawn, but thoughtful, tragicomic vision of impoverished indigenous life, with allusions to Gulpilil’s background as a dancer and his public struggles with alcoholism. De Heer works in understated audiovisual gags: a buffalo hunt that happens entirely off-camera, playing out as dialogue and sound effects over a shot of swaying woodland; Charlie and Black Pete caught by cops with a water buffalo strapped to the hood of their truck; local men hanging out and drinking beer at the edge of the reserve’s alcohol-free zone.

Part of the movie’s mischievous charm lies in De Heer and cinematographer Ian Jones’ sophisticated use of Steadicam, which moves almost exclusively with Charlie, often seemingly in a struggle to keep up with his brisk, determined walk. It taps into the immediacy of Gulpilil’s performance, whether he’s baking a barramundi in a pile of cinders, sneaking around a hospital, or delivering a non-verbal punchline. (Gulpilil’s sharpy, raspy “Naaah…” is a thing of aural beauty.) This special relationship—the camera seemingly of a wavelength with an actor so often typecast as ambiguous or opaque—takes on a dimension of sadness in an extended section that finds Charlie in prison, unrecognizable to his friends without his beard and long curly hair. The walls and corridors seem to imprison the camera, too; its loose, limber style gives way to angular compositions, and a viewer begins to feel the loss of freedom in the edges of the frame.